Sensing something wasn’t right, the lion popped his head out from behind the tree. Instantly, his big eyes blazed like coals and he issued a deep, rumbling growl.

It was a hot and dry September day in Tanzania, just south of the little village of Loiborserrit. We left our camp under the stand of tall fig trees and drove off in the hunting car with clients Clarence and Carol, bouncing over tracks someone had the audacity to call roads. We were looking for a good lion in a heavily hunted concession, which meant the big cats were well-educated and keeping to cover during the day.

It was a hot and dry September day in Tanzania, just south of the little village of Loiborserrit. We left our camp under the stand of tall fig trees and drove off in the hunting car with clients Clarence and Carol, bouncing over tracks someone had the audacity to call roads. We were looking for a good lion in a heavily hunted concession, which meant the big cats were well-educated and keeping to cover during the day.

About 40 miles from camp we happened upon some promising tracks and immediately set out to acquire some bait for our blinds. By late afternoon we’d collected an old buffalo bull, then cut up and tied the hind-quarters at two sites several miles apart. Close by the bait trees we built ground blinds that blended in perfectly into the surrounding brush.

“Cat’s in the bag,” I jokingly bragged on the torturous drive back in the utter blackness of an African night.

The next morning found me relaxing in my tent, listening to mourning doves and green pigeons and my staff preparing breakfast. The couple had bagged everything except a lion, and I was determined to leave the baits undisturbed for at least two days. Other than a few hours of bird-shooting, sitting around camp seemed like a good choice.

My tent man brought hot shaving water, poured it into the canvas washbasin and hinted that bwana should get his rear end in gear and shave. While shaving, I noticed a respectable bank of clouds — definitely rain clouds — but in September? The clouds continued to build up throughout the day and by afternoon, the humidity was oppressive, the air warm and still.

In the wee hours of the following morning the heavens opened and rain cascaded down, accompanied by streaks of lighting that crisscrossed the sky. Water rushed everywhere and so did we, hammering in longer tent pegs to prevent our tents from collapsing. By noon the rain was falling steadily and the little watering hole next to the camp had become a small lake.

In the wee hours of the following morning the heavens opened and rain cascaded down, accompanied by streaks of lighting that crisscrossed the sky. Water rushed everywhere and so did we, hammering in longer tent pegs to prevent our tents from collapsing. By noon the rain was falling steadily and the little watering hole next to the camp had become a small lake.

The deluge didn’t stop until early the next morning, and by sunrise the dry bushveld was alive with the sounds of insects, birds and even the hysterical laughter of a hyena scouting out our camp.

This will be Clarence’s day, I thought, though we’ll probably have to put up with more rain.

After loading our guns and gear in the Land Cruiser, we headed to the closest bait, plowing through muddy, red water and with the tires slinging mud in all directions.

About five miles from the blind, my Number One bearer and I left the vehicle and walked to the bait site. Our approach was good, but the last few hundred yards were tricky because of sparse cover. Finally, we reached a big acacia bush where we stopped to glass the bait and surrounding area.

Suddenly, Number One began nodding his head, like Kavirondo cranes during their mating rituals. I never could understand how he could see better than me, especially with my Zeiss binoculars. He had spotted something out of the ordinary, perhaps just a shadow, ghosting through the dense thorn brush. Number One was all for taking a closer look, to find long mane hairs, proof of a good lion, but something told me to back off, as simba might be close.

Suddenly, Number One began nodding his head, like Kavirondo cranes during their mating rituals. I never could understand how he could see better than me, especially with my Zeiss binoculars. He had spotted something out of the ordinary, perhaps just a shadow, ghosting through the dense thorn brush. Number One was all for taking a closer look, to find long mane hairs, proof of a good lion, but something told me to back off, as simba might be close.

After checking the second bait, which had not been touched, we stopped to eat lunch and quench our thirst under the shade of a big tarp. The air was hot and muggy, and we could see another mountain of dark clouds coming toward us from Ol Doinya Lolbene near camp.

Despite the approaching storm, I thought our best bet was to hunt from the first blind — to give it a shot, rain or no rain, because our area permit would expire in a couple days and we had to leave. Number One thought bwana was off his rocker, but was willing to follow my intuition.

The rain was pouring down when he stopped the vehicle and once on the trail, we were quickly soaked to the skin. Clarence’s wide-brimmed hat lost its shape and it appeared he would need windshield wipers to keep the water off his trifocals. At least the rain felt pleasantly warm.

We slipped and slid the last 200 yards to the blind, where the downpour blanked out everything but a faint outline of the bait tree. The thunder rumbled while raindrops drummed on the parched soil and splattered the leaves and branches; at least the noise would cover our approach.

Huge drops continued to bombard us as we hunkered down inside the blind, our boots covered in mud. I focused my binoculars on the bait and the area around it, but failed to see anything. I wondered: Can a person get any wetter than wet . .. or be more miserable and have such fun?

Huge drops continued to bombard us as we hunkered down inside the blind, our boots covered in mud. I focused my binoculars on the bait and the area around it, but failed to see anything. I wondered: Can a person get any wetter than wet . .. or be more miserable and have such fun?

Late that afternoon, as the rain let up and our visibility improved, Number One and I really began to concentrate. I had to wipe my binos constantly, though Clarence didn’t seem to notice; he was bent over like the Hunchback of Notre Dame, and I don’t think his mind was on lion hunting.

And then I saw him, looking as ragged and wet as us, walking over to the bait tree to get out of the wind and rain. Breathless minutes passed. How long would he stay there? Would he even come out to eat in the rain?

Dusk was approaching and if we waited, good shooting light would soon be gone. In my mind, our only chance was to leave the blind and stalk closer. Number One said it might work, but Clarence thought stalking a lion in the rain was something only a crazy East African hunter would do. It was crazy, I admit, but soon all three of us were crawling over the wet grass and mud toward the big tree. It seemed like hours had passed before we were within 20 yards of the tree and the remains of the buffalo dangling from a heavy limb. I figured it was time to stand, abandon caution and see what in hell was going to happen. We were certainly well-armed for whatever came next; I had my .416, Number One carried a .416 and Clarence his .375. You need that kind of firepower in a situation like this.

Fifteen paces … ten … then I was so close to the tree I could have reached out touched it with my rifle barrel.

Sensing something wasn’t right, the lion popped his head out from behind the tree. Instantly, his big eyes blazed like coals and he issued a deep, rumbling growl. Then, like hot oil gushing from a drum, his huge, tawny body seemed to flow around the tree as he flung his huge paws right at my head. Three heavy-caliber bullets tore into his head, neck and chest, and old simba dropped heavily to the soggy ground, barely a step away from my feet.

Sensing something wasn’t right, the lion popped his head out from behind the tree. Instantly, his big eyes blazed like coals and he issued a deep, rumbling growl. Then, like hot oil gushing from a drum, his huge, tawny body seemed to flow around the tree as he flung his huge paws right at my head. Three heavy-caliber bullets tore into his head, neck and chest, and old simba dropped heavily to the soggy ground, barely a step away from my feet.

Hours later, after a good meal and with some elixirs to warm our bodies, the rains finally stopped and the southern sky was once again studded with stars. We sat around the campfire, reliving our adventure and trying to make sense of the heavy rains that seemed so out of sync with the season. But my gunbearers had the answer: The heavens had to weep, because a simba died.

Editor’s Note: Born in Tanzania (East Africa) in 1933, Robert Reitnauer was formerly a fully licensed Professional Hunter and Safari Operator in southern Africa.

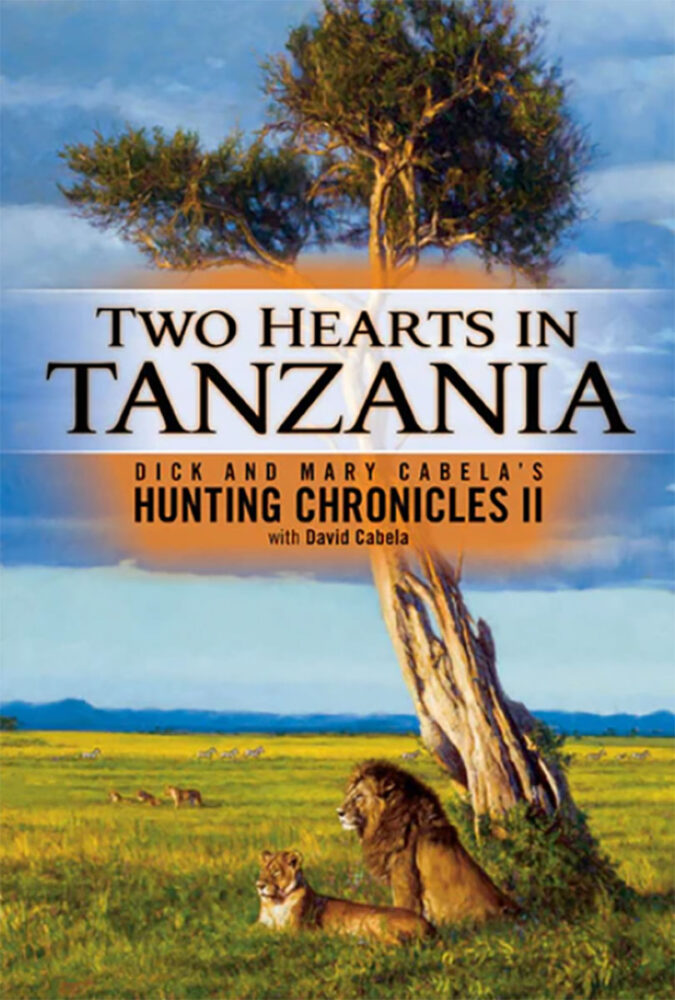

Told in first-person with the warmth of a hand-written journal, Two Hearts in Tanzania puts you right in the thick of the action and in the hearts and minds of the people who lived these amazing adventures. Illustrated with chapter-opening sketches by famous wildlife artist, John Banovich, the book includes 16 pages of photos of African wildlife, native peoples, hunters, trackers, camp life and Dick and Mary with their hard-won trophies. Also includes a 15-minute DVD attached to the inside back cover of the book that features interviews with Dick and Mary, footage from their safaris, and observations on Tanzania and big-game hunting. Buy Now

Told in first-person with the warmth of a hand-written journal, Two Hearts in Tanzania puts you right in the thick of the action and in the hearts and minds of the people who lived these amazing adventures. Illustrated with chapter-opening sketches by famous wildlife artist, John Banovich, the book includes 16 pages of photos of African wildlife, native peoples, hunters, trackers, camp life and Dick and Mary with their hard-won trophies. Also includes a 15-minute DVD attached to the inside back cover of the book that features interviews with Dick and Mary, footage from their safaris, and observations on Tanzania and big-game hunting. Buy Now