There’s the greatest writer of the last century and wanderings across the continents with gun and rod, and it begins in 1951 just outside Havana

Way up in the Sawtooths, the day comes creeping on the wind. The aspens rattle and the stars fade as the first light hits the great jumble of peaks and tells you how this place got its name. The wind ghosts up the mountain and whispers stories to those with ear and heart to hear. Stories of the Ancient Ones, the Sheep Eaters. Stories of the cavalry and miners and cowpokes and swindlers and bums and magnates. And finally the story of a man who loved this place, then came back here to die.

Ernest Hemingway. We love his work and puzzle over the man, this great and tainted genius. When we know the story, our puzzling ferments and ages like good wine, and it becomes smoky and sweet with an aftertaste like the morning wind in the Idaho hills.

No ordinary man and certainly no ordinary story. There’s the greatest writer of the last century and wanderings across the continents with gun and rod, and it begins in 1951 just outside Havana in a ramshackle stone farmhouse on a hill overlooking the sea.

Locals call it la Finca Vigia, the view farm. Little wonder. Below is the surging Caribbean, breaking upon a labyrinth of coral. Beyond is the Gulf Stream, home to trophy billfish and tuna and dolphin and great toothy wahoo.

Behind the house is a sunny patio and a swimming pool, where Ernest Hemingway swims laps while a woman reads a magazine and sips her gin and tonic. Ernest Hemingway is lately famous and very prosperous from The Old Man and the Sea, the book about a Cuban fisherman and a big fish that sold 50,000 copies in its first three weeks and is now selling 1,500 copies a day.

The woman is Mary Welsh Hemingway, a fine sliver of the Scandinavian gene pool from far northern Minnesota. She is tall, blonde, gutsy, formerly a war correspondent for Time and Life magazines. It’s her third marriage, his fourth.

Mary sighs, proclaims her boredom. Ernest Hemingway breaks his stroke and stands to catch his breath. “Let’s hunt birds in Idaho,” he says.

Ernest Hemingway was a man of his word. He could coolly squeeze the trigger before charging African game. He could fight a blue marlin four times his weight for a full day with a flask of rum but without a jigger of complaint. He could hike and ski and wingshoot and drink and box to put most men to shame. But with women, he was a little shaky.

Which was why Ernest Hemingway knew Idaho. He went there in 1939, when he was between wives and looking for a place to hole up and write. Sun Valley is where Averell Harriman, president of the Union Pacific, built a ski resort to boost wintertime ticket sales on his railroad. As a publicity ploy, Harriman invited the rich and famous, threw in free rooms and sumptuous meals, then used the celebrities names in various advertising blitzes. Ingrid Bergman came, so did Robert Taylor and Clark Gable.

Harriman set Hemingway up in Room 206 where he wrote mornings and ventured forth to hunt and fish in the afternoons. Between times, he posed for publicity pictures. The man behind the lens was Lloyd “Pappy” Arnold, a serious outdoorsman who introduced Hemingway to another hunter, resort publicist Gene Van Guilder, and to Taylor “Beartracks” Williams, the area’s best-known guide.

Pheasants cackled in the hills and mallards dipped into the backwaters of Silver Creek and the Big Wood River. Gene, Beartracks, Pappy and Papa Hemingway, as he increasingly called himself, went after them at every opportunity. Hunting ducks one Sunday morning, Gene Van Guilder was killed by a blast from a mis-handled shotgun. Hemingway, abed and nursing a hangover, was spared watching his friend die. He delivered the eulogy, reading at the windy gravesite words he had typed the night before. “ . . . best of all he loved the fall. The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods. Leaves floating on the trout streams and above the hills, the high blue windless skies. Now he will be part of them forever.”

Hemingway returned to la Finca Vigia to work on For Whom the Bell Tolls, but in the fall of 1941 he was back in Idaho. Beartracks Williams introduced him to the Old Timer, known by no other name, who hauled Arnold and Williams and Hemingway to his bug-infested shack in the Pashsimeroi Valley – Shoshone for “water and the one place of trees.” There around the campfire the men heard the Old Timer’s stories, tales of Custer’s death at the Greasy Grass, and the Wagonbox fight, where sixty-seven woodcutters faced down two thousand Sioux.

The men chased antelope for two days without success. The third day out, they spooked a herd up into a blind canyon. There was only one way out and Hemingway saw it, ran for it, first on horse, later on foot, clambering over rocks while clutching his battered Springfield .30-06. He made it just in time. “They came streaming over the hump,” he later wrote. “I picked the biggest buck and swung ahead of him and squeezed gently and the bullet broke his neck.” Arnold saw it all and told the story for years.

But high society was calling. Down the mountain at Sun Valley, Gary Cooper and Robert Taylor were waiting to talk to him about the movie potential for For Whom the Bell Tolls, which had sold a half-million copies. And then there were the bars, the heated pools and roulette wheels.

After declining an invitation to speak at a book convention in New York City, Hemingway took off in the other direction. On December 4th, he was gazing into the depths of the Grand Canyon. The news of Pearl Harbor reached him when he was crossing the border into Mexico. So Ernest Hemingway, wounded in the first war, went to war again, first chasing German submarines in the Caribbean aboard his beloved Pilar, then covering the Normandy invasion, finally winning a Bronze Star as a leader of a troop of French partisans who fought their way into Paris considerably ahead of the U.S. Army.

After the war, there was la Finca again. He was far offshore, fishing the Gulf Stream when the radio crackled with the news he had won the Pulitzer Prize. Hollywood was calling by the time he got to shore. He celebrated by buying a yellow Plymouth convertible and planning a trip to Africa. He had been there 20 years before and his book, The Green Hills of Africa, had been a modest success. Now he had the money and the time and he was going back.

And now there was Mary Welsh Hemingway, his fourth, last, and best wife. The first leg of the African trip took them to hotels and bars in Key West, New York and Paris, and then on to hotels and bars and bullfights in Spain. In Mombasa, they were met by Phillip Percival, who had begun his career guiding Teddy Roosevelt in 1909 and served Hemingway equally as well in 1933. They struggled uphill to Kenya, some 6,000 feet above the sea.

There at Percival’s farm, the campfires were blazing. There awaited six tents, four trucks, 700 pounds of food, two dozen cases of whiskey, double rifles, double shotguns and .22s for taking camp meat. There was N’gui, the gunbearer, who would not shirk his duty when charged by lion or elephant; M’kao, the skinner and tracker who could read signs in the earth at a full run; M’thoka, the hunting car driver; ebony and bony M’windi, too old to do much else, who washed clothes and cleaned tents; and so on down the ranks until there were twenty-two Wakamba tribesmen ready to head off up the Salengai River.

“It was a green and pleasant country,” he wrote, “with hills below the forest that grew thick on the sides of the mountain, and it was cut by the valleys of several watercourses that came down out of the thick timber on the mountain…and it was there by the forest edge that we waited for the rhino to come out.”

But by odd coincidence, the first rhino came looking for him. A Kenyan warden stopped them on the road. A poacher had wounded a rhino, now sorely aggrieved and eager to trample the next person he met. Would Bwana like a crack at him?

Indeed, Bwana would. He uncased his Westley Richards .577 double, popped two rounds into the chambers, slipped a few more into his pockets, and took up the trail. The beast charged and Hemingway got off two quick shots, the nearest from 12 yards. The rhino careened off into the dust and gathering gloom. Hemingway spent a restless night, but in the morning the trackers found the beast, the bullet holes where Hemingway wanted.

Now they had their first trophy and lion were next. They shot two zebras, hauled the carcasses to likely spots, and set up baits. The local Masai heard the shooting and drifted into camp, greeting the hunters and their Wakamba crew by striking the ground with the butts of their long home-forged spears and saying “Jambo, Jambo.” The taciturn and unflinchable Masai were much amused when Hemingway began plugging holes in half dollars and shooting cigarettes from their hands with his .22. Impressed, they disclosed the real reason for the visit. Lions had been killing their cattle. Would Bwana care to thin them out?

Once again, Ernest Hemingway was happy to oblige. A week later he took a poke at a big male in the half-light of dawn. Through they heard the bullet whock home, there was no roar and little blood, and the lion vanished into the brush. Percival joined the posse to root him out. A long harrowing hour and four shots later, the lion was dead, though Hemingway did not kill it.

Hoping for magic and a change of luck, Hemingway cut a sliver from the cat’s backstrap, ate it raw. The Masai set up a great wail. Though they would open a cow’s veins and lap blood like vampires, a white man eating lion flesh was too much for their sensibilities.

Whatever luck Hemingway had hoped would follow that bloody snack did not materialize. A week later he missed a Cape buffalo in the Kimana River Swamp, in the shadow of Kilimanjaro. He switched to his worn and trusty Springfield – the same rifle that took the running antelope and made three dozen one-shot kills on his first safari – and bagged a zebra and a gerenuk. But then he started missing again. Mary shot a kudu at 245 yards with a 6.5 Mannlicher, but Hemingway’s bad luck continued. He fell out of the Land Rover, battering his head and throwing out a shoulder.

But life offers compensations, as Teddy Roosevelt noted in 1909 when he went on safari instead of moving into the White House. A half-century later, another one of Percival’s clients set out to prove it once again. Hemingway – as fine a wingshot as ever – took lesser bustards and francolin and guinea fowl and sandgrouse almost daily.

Hemingway’s work with the rogue rhino and the cattle-killing lion earned him the status of honorary Kenyan warden, with powers of investigation and arrest. He toured the countryside, responding to elephant raids on cornfields, and lion and hyena predation on donkeys and cattle. He knocked a leopard out of a tree and went after it on his belly with a Winchester pump-gun, shooting at close range until “the roaring stopped.” Look magazine ran a picture of the bearded Bwana and old Chui, the spotted one.

And then there was Debba, the winsome Wakamba girl from the nearby shamba. Hemingway, typically outrageous, mentioned his lustful thoughts to Mary, who wryly suggested old M’windi give Debba a bath first. Hemingway waited until Mary flew up to Nairobi to do some shopping. She came back to find her bed broken, and the Greatest Living Writer in the English Language practicing with a spear and running about in shorts dyed various shades of Masai gray, pink and ochre.

Hemingway’s run of bad luck only got worse. On January 21, 1954, he and Mary boarded a Cessna 180 at West Nairobi airport for sightseeing and photography above the White Nile and the Great Rift Escarpment. Three days later while circling low over a spectacular waterfall, the pilot clipped a telegraph cable, severing the radio antenna and most of the rudder. They made it another three miles before plowing into the thorn trees.

The pilot was jostled but otherwise unhurt. Ernest had a mild concussion, another injured shoulder and Mary was in shock. The trio struggled up a hill, built a fire and was spotted by a river streamer the following day. By then, news had flashed around the world that Ernest Hemingway was missing somewhere in Uganda and presumed dead.

The steamer deposited them at Lake Albert, where they boarded another aircraft – a decrepit De Havilland bi-plane – bound for the hospital at Entebbe. They never made it off the ground. Mary and the pilot shinnied out a tiny shattered window. While flames licked toward the fuel tanks, Hemingway rammed and kicked and butted his way through a jammed side door.

He was alive, but badly hurt. He was bruised and burned, but worst of all, his fractured skull was leaking blood and cerebral fluid. And it was still 140 miles to the hospital, two days by potholed and rutted Ugandan roads. Halfway there, they stopped for food and drink, and sympathetic bar patrons poured gin into Hemingway’s open head wound, proclaiming the superiority of Ugandan bush medicine and predicting a speedy recovery.

But it was not to be. Ernest Hemingway, suddenly old at fifty-four, was never quite the same. He suffered flashes of black anger and irrational outbursts. And there were deep and recurring depressions, delusions of both grandeur and persecution. After briefly recuperating in Nairobi, where he claimed he was treating his burns with lion fat, and fishing on the Indian Ocean where he caught little, Hemingway returned to Europe. There he consorted – as best as he was able – with an old but very young lover, the lovely Adriana Ivancich, whom he had bedded years before in Cuba.

Eventually Hemingway made it back to la Finca Vigia, where he fished with Ava Gardner, Hollywood’s hottest that year, after hours trolling her around the Havana nightspots, provoking a minor frenzy among young Latino night-lifers.

Mary remembered the early morning of October 28, 1954. She had slept alone, which was her custom, when her husband crawled in alongside and woke her with a throaty whisper. “I’ve won the thing.”

“What thing?”

“The Swedish thing,” he murmured.

Ernest Hemingway had won the Nobel Prize for Literature. But the black mood that had settled upon him was taking its toll. “I’m thinking of telling them to shove it.” But he reconsidered. “Hell, it’s $35,000. A man can have a lot of fun with $35,000.”

And he did. He went back to Idaho. But there were other considerations. Hemingway had lately written, “I am a man without politics. This is a great defect but it is preferable to arteriosclerosis.” But he was an American in a country where Castro and Batista were waging a bitter civil war. After a nervous patrol of government conscripts assassinated one of his favorite dogs, Hemingway headed north by northwest.

By then Hemingway was too famous and Sun Valley too touristy. The defunct mining town of Ketchum was just across the river. Mary recalled “ . . . wooden boardwalks on either side of the two blocks long mainstreet, which was also Highway 91 heading toward Alaska . . . there was no bank but all the bars cashed checks. Canned milk and pinto beans and homegrown cabbage . . . in the only grocery store, whose front window displayed not merchandise, but a long row of slot machines.”

The high-country climate suited Hemingway, who was finally limbering up after his two plane crashes so that he could swing on a bird once again. The Hemingways shot mallards and pintails, chukars, pheasants and sage grouse. They even chanced another airplane ride, that took them far up into the mountains – in a howling snowstorm – to hunt mule deer.

Up in Idaho, they still talk about those days. Patti Struthers, now in Albuquerque, was a teenager who remembers a big man with a charisma that filled every room he walked into. Still, she was afraid of him. “There was something about him that I did not like.” Was it sex? Maybe so. “He spent some time with one of my girlfriends,” Struthers says. “She seemed to be alright with it, but it gave me the creeps.” Complex as always, Hemingway taught Patti’s mother how to handle a shotgun.

At 81, Margaret Struthers’ recollections are still vivid. “It was a double sixteen he had bought for his boys. We went out to the range and I got good enough to kill ducks we flushed from the irrigation ditches. Ernie would lay out a plan and we’d crawl on ’em. Nobody dared stand and shoot till he gave the word.” And despite his legendary penchant for alcohol and recklessness, Margaret Struthers remembers a man who brooked no drinking until the limit was filled, the guns unloaded and cased. “He was very careful about that.”

Hemingway and Margaret’s brother, Bud Purdy, tried to introduce live pigeon shooting to Idaho, a sport Hemingway enjoyed in Cuba. The lack of sufficient pigeons proved no obstacle. The men used magpies, a bird rated by local ranchers as somewhere between a crow and a buzzard. There was a ten-cent bounty on them in those days, and Hemingway figured it would pay for the shells. Bud Purdy engineered the traps, which looked like giant lobster pots and often netted a hundred or more birds when baited with a sheep carcass. “We’d send the kids in to sack ’em up,” Purdy recollects. “They didn’t mind too much.”

The magpies were released from a gunnysack, one bird at a time. “There was a shooter and a backer at each side,” Bud says. “The backers couldn’t fire until the shooter got off two rounds.” Hemingway and Purdy were often joined by Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, and once even by the Shah of Iran. Hemingway usually won, and one year was presented with a Magpie Trophy that proudly sat on the desk in his Ketchum home.

Meanwhile, there was trouble back in Cuba. Batista had fled and Castro and his band of bearded revolutionaries were in Havana and the first “Yanqui go home” graffiti was appearing on the city’s walls. La Finca was in bad shape. The Hemingways went back, ordered maintenance and repairs. That chore finished, it was time for fishing. Hemingway and other international sport-fishermen organized a billfish tournament and invited Fidel Castro as a sign of good will. Castro won, though Hemingway, watching through binoculars, thought he saw one of Castro’s security goons at the reel, a flagrant violation of the rules. Nevertheless, in the absence of irrefutable proof, he had to present Castro with the trophy. Hemingway, who loathed any sort of phoniness, left Cuba for the last time.

On November 30, 1960, one George Seviers was admitted into the Mayo Clinic at Rochester, Minnesota, for treatment of high blood pressure. Seviers had been flown in from Ketchum, and while refueling at Rapid City, he had attempted to walk into a whirling propeller. Seviers was also being treated for chronic depression. But it was a ruse to throw off the press. The real George Seviers was a medical doctor and still at home in Ketchum. The man in the Mayo Clinic was his patient, Ernest Hemingway.

His doctors ordered electroshock therapy, where a patient is strapped down and jolted with near-fatal charges. Hemingway seemed to respond well, and after a few weeks, was following his doctor home for meals, drinks and trapshooting. But electroshock therapy has one great and debilitating side-effect – the loss of memory. Hemingway wept when he could not remember the name of the swamp where he had missed that Cape buffalo back in 1953.

Then came a final indignity. Hemingway had been invited to the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, but was too ill to attend. The President had sent a copy of The Old Man and the Sea, asking for a line or two and an autograph. Hemingway stared at the page for most of the afternoon. The man who had written a dozen books and perhaps a thousand shorter pieces, the man who had won both the Pulitzer and Nobel prizes, could not think of a single line for the President of the United States.

Back in Ketchum, on July 2, 1961, Ernest Hemingway rose early. He padded to his gun cabinet, chose a fine Boss Pigeon Grade, put the barrels to his forehead and snatched both triggers.

He was buried in Ketchum’s cemetery. His epitaph on a memorial erected by his Idaho friends was the one he had written for Gene Van Guilder back in 1939. “Best of all he loved the fall. The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods. Leaves floating on the trout streams and above the hills, the high blue windless skies. Now he will be part of them forever.”

But the question haunts us still. How could he do it? He had fame, boats, cars, guns, women, whiskey, the best shooting and fishing on earth. How could this man who had repeatedly foiled death in war and love and sport do this to himself?

Hell, how could he do this to us?

Out in the Sawtooths, the day ends early as the sun slips behind the jumbled peaks. A coyote howls as the last of the light ricochets off the tallest mountains. The shade creeps, then rushes, and the lonesome sky deepens from blue to purple to violet to beyond human sight. The first pinprick stars glimmer and the valley cools and the wind eases back down the slopes, rattling the aspens like Ezekiel’s dry bones. Ezekiel’s bones prophesized, but the aspen do not and the question remains on the wind.

And you turn from this place and you think he was old and sick and could no longer do what he lived and loved to do. And he did it with a fine twenty-bore. He did it in style.

Maybe that’s answer enough.

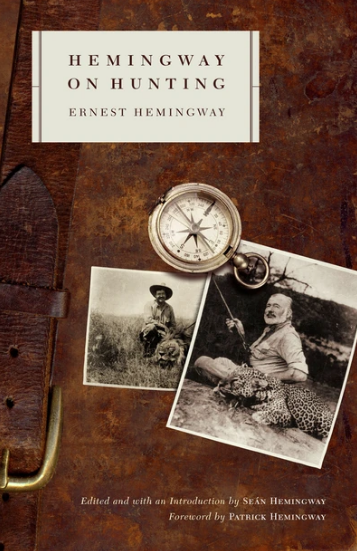

Ernest Hemingway’s lifelong zeal for the hunting life is reflected in his masterful works of fiction, from his famous account of an African safari in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” to passages about duck hunting in Across the River and Into the Trees. For Hemingway, hunting was more than just a passion; it was a means through which to explore our humanity and man’s relationship to nature. Courage, awe, respect, precision, patience—these were the virtues that Hemingway honored in the hunter, and his ability to translate these qualities into prose has produced some of the strongest accounts of sportsmanship of all time.

Ernest Hemingway’s lifelong zeal for the hunting life is reflected in his masterful works of fiction, from his famous account of an African safari in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” to passages about duck hunting in Across the River and Into the Trees. For Hemingway, hunting was more than just a passion; it was a means through which to explore our humanity and man’s relationship to nature. Courage, awe, respect, precision, patience—these were the virtues that Hemingway honored in the hunter, and his ability to translate these qualities into prose has produced some of the strongest accounts of sportsmanship of all time.

Hemingway on Hunting offers the full range of Hemingway’s writing about the hunting life. With selections from his best-loved novels and stories, along with journalistic pieces from such magazines as Esquire and Vogue, this spectacular collection is a must-have for anyone who has ever tasted the thrill of the hunt—in person or on the page. Buy Now