Three-fifths of the world is water and the wind courses over all of it. So when Pappy gave me that 10-foot bateau, he gave me the world.

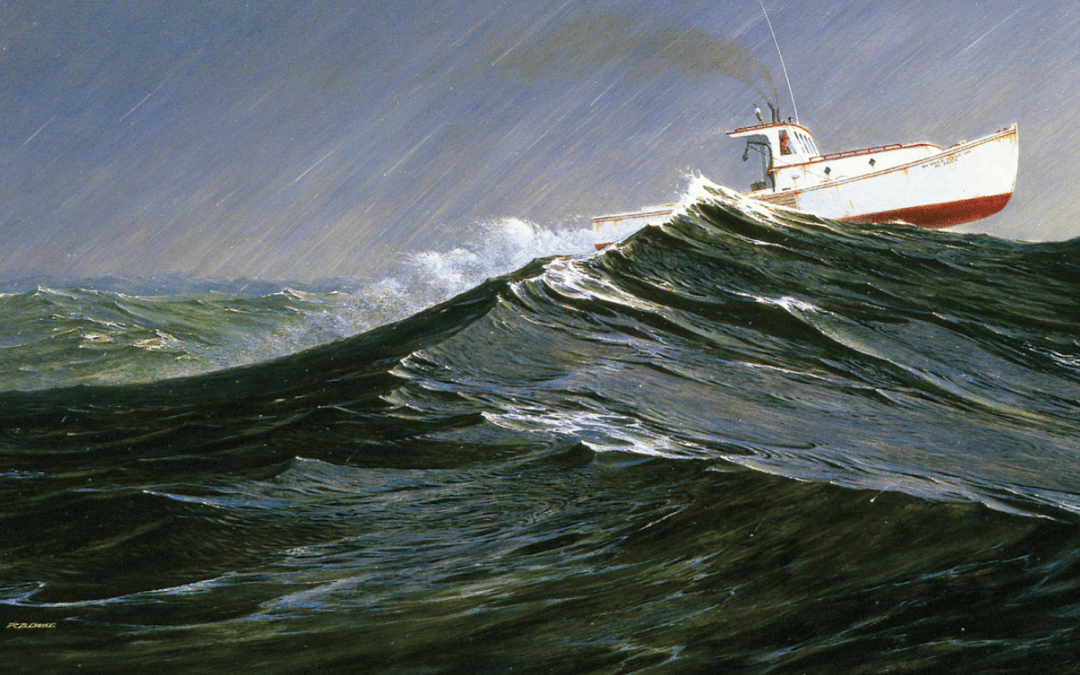

The first swell smacked the port quarter, sent green water clean over the wheelhouse. Aboard Maggie C, a 26-foot Maine Lobsterman, round bottom and rolling like a pig. On the edge of the Stream, no land in sight.

The boat staggered, fell off to starboard. Auto-pilot couldn’t hold her.

In the few seconds it took to disengage the damn thing and grab the helm, we were headed back the way we’d come, and the seas were breaking over the stern. The bilge pump kicked in, a considerable satisfaction, though I could barely hear it above the crash and roar.

We’d been laid up three days in a south Florida marina, waiting out the wind while the ice melted and the rations soured. Squoze down between Florida and the Bahama Bank the way it is here, the stream runs four knots, sometimes five. Don’t try a crossing if there is even a whisper of “northerly” in the marine forecast.

I didn’t know it then, but I damn sure do now. The wind was down to ten knots when we took our chances.

Great God, what a crossing! Wind against the current the way it was, it rolled the water up like you were petting a cat backwards. Ten-foot swells. Three of us, the captain, me and Scotty, too suddenly occupied even to break out life jackets. The Zodiac dingy in tow flipped, wallowed in the wake, everything aboard lost to the storm. I made a line off on a side cleat, tied the other end around my waist and grabbed Scottie by his belt as he struggled the dingy aboard. One slip and he was good as dead.

We took the helm in shifts. Half an hour was all any of us could stand. We collapsed in turn, moaning upon a bunk, rubbing elbows, shoulders, wrists. Then each took the helm again till Gun Key hove into sight. The Stream had swept us north 20 miles. It was the worst crossing of my life, until the Grand Bahama Bank two days later.

That’s a whole nuther story but meanwhile I was fixing to drown us all.

The captain pulled out a dog-eared and water-stained chart, folded this way and that until it was the size of a cigar box, Bimini in the center.

“Look for two tall stakes, it says, line ’em up for safe passage through the reef.”

His glasses were crusty from seawater. He squinted through the windshield, smeared and crusty too. “Can you make ’em out?”

I was taking another shift at the helm. “Dead ahead,” I said.

The captain backed off on the throttle, nodded. But then his brief satisfaction turned to terror. “Great God man! Those are power poles! You are fixing to run us aground!”

Coral down there has no mercy, rip the bottom out of a boat quicker than it takes to tell you. The captain snatched the wheel, jammed the controls into reverse. The gearbox rumbled, whined and the boat shivered stem to stern, bucked but backed down an instant before she struck.

Safe inside the harbor, we moored at Weech’s Marina, where Papa Hemingway had tied up 50 years before. Scottie grabbed a jug, took a good long pull. It was Jim Beam, the King James Version, we called it.

“Beam me up, Scottie,” I said.

He did.

I came into the world in the usual way but shortly thereafter, there was scarcely a normal day. The Carolina Lowcountry, maybe you know it, that watery wilderness between the Great Santee and the Great Savannah, two rivers that define my soul, the estuaries, inlets, sounds and side creeks in between, two-thirds of it underwater at high tide. If you strung out all this coastline, our 150 miles would be longer than the entire coast of California.

On my 10th birthday, Pappy gave me a boat, not a bicycle. Appropriate to the geography.

They called it a bateau and if you could afford more than one, it was bateaux. They were flat-bottomed, hard chined and came in assorted sizes, 10 to 24 feet, though the larger ones were called 50 bushel or 100 bushel, the amount of oysters they could carry.

Mine was a beauty: 10 feet, oak frame and oh so thin cypress along the sides, so nimble she’d throw a wake with just the oars. Good thing, as there was no motor, no place even where a motor might fit. There were no life jackets either, a curiosity continuing to this day.

Learn the river, son, and mind your wind. Have fun and for God’s sake, don’t drown your fool self.

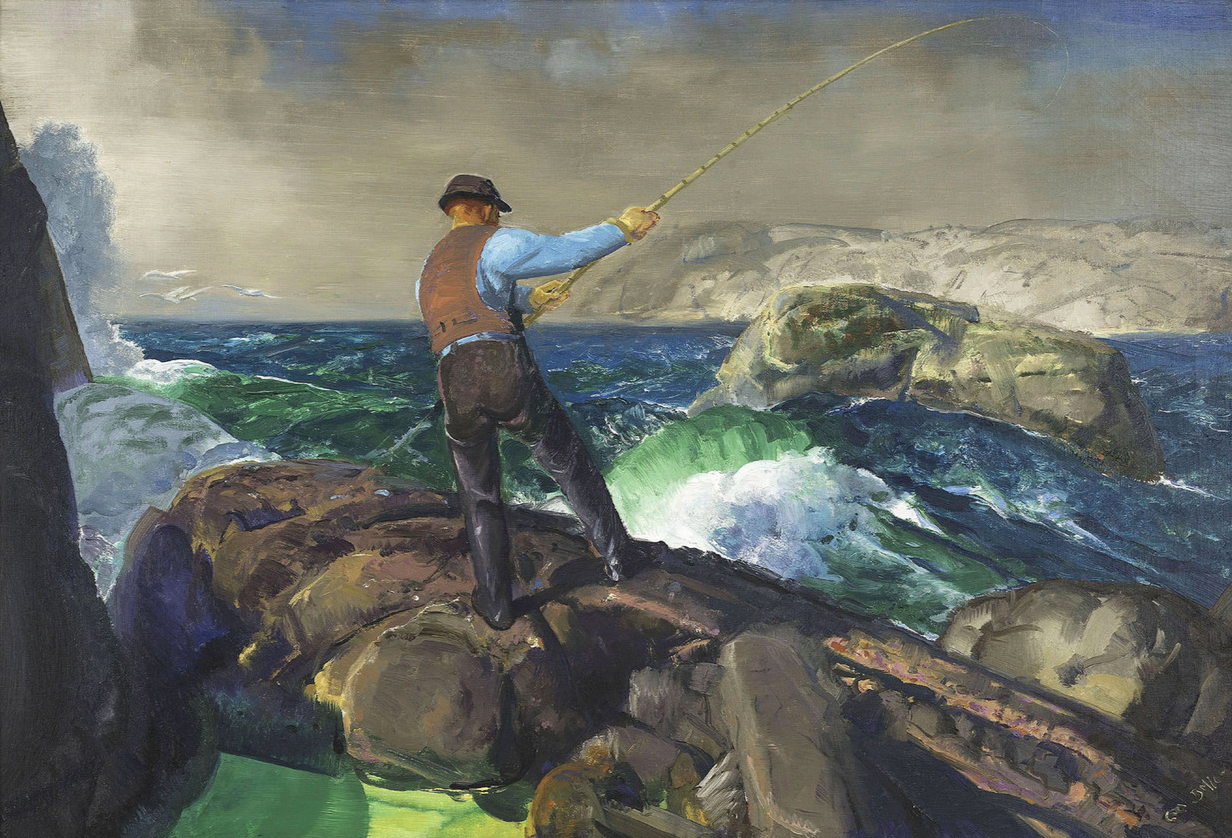

Daytrips and sack lunches, Vienna sausages, sardines and soda-crackers, a Honey Bun and a Dixie Cola, sometimes a few beers if I could swipe them out of the ice box. I’d ride the ebb tide out, ride the new flood home. Hunting, fishing, throwing the net, picking oysters and clams, mostly just loafing, barefoot, cut-foot, sunburnt, free and wild, it was a mighty fine time to be a boy.

Pappy took that little bateau back five years later, replacing it with a 16-footer with a tiller steer Evinrude 18 and my 10-mile round trips suddenly became 30, even 40. My comrades were similarly equipped, and we tacked together a tin-roof fish camp on a remote barrier island, spending nearly every weekend entirely unencumbered by any adult supervision for the next half-dozen years. If it wasn’t heaven, it was close enough.

The child is father to the man, the poet says. Blasted, windblown, shot at, cast ashore and marooned, I suffered severely from that lack of sensible supervision from adults.

Pappy said don’t drown my fool self. I didn’t but I came close.

Twenty-five hundred miles from Bimini, along the shore of a nameless lake along the Little Churchill River 50-odd miles southwest of Hudson’s Bay.

Nameless. There are a half-million lakes in Manitoba, more than words in English, Ojibwe and Cree combined. The provincial government gave each an eight-digit number instead to avoid obvious confusion from having one 127 Fish Lakes. Locals might have given the lakes names, but there were no locals, none whatsoever.

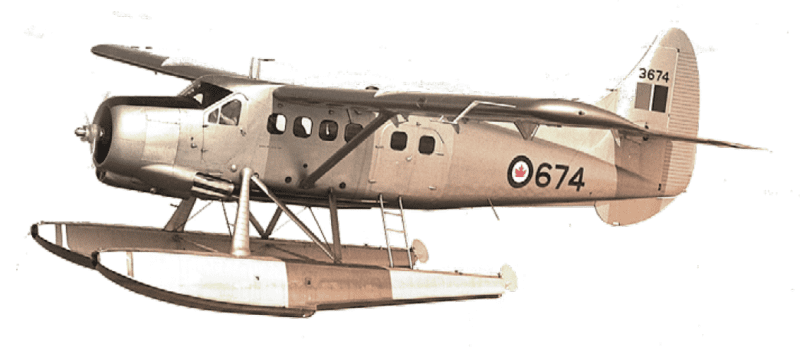

The road ran out at Thompson some 200 miles away. Rapids above the lake and rapids below, you could not get there by boat. Snow machines in winter? Nope. The muskeg cooked below ground, heat from the fermenting mass of cattail roots kept the ice sketchy, even at 40 below. The only access was by floatplane, in this case a 1956 de Havilland Otter loaded with jerry-cans of gasoline, a 15-horse outboard Mercury, a hundred-pound bottle of propane, a rifle and me. It was a non-smoking flight.

There were boats at the lodge— 16-foot aluminum Lunds flown in as needed, lashed to the Otter’s pontoons. Other guests were fishing, but I was hunting black bear. They were hammering the pike, the cook was saving the guts and heads, and I was running a half-dozen bear baits.

It worked like this: Six piles of logs along a 40-mile route, logs too heavy for a fisher or wolf, ripening pike below. Each was in a bay or on a point, visible from the water. I brought along wire survey stakes; you know, those orange and yellow little thingies you get when you Call-Before-You-Dig. I’d twist a loop in the shank, fix it to a log with a shingle nail, then bend it down and fix it to another log with fishing line and a clothespin. If anything fooled with it, the flag would pop up and show from offshore.

Brilliant, indeed. But everything fooled with them, from chipmunks to ravens. They never got the bait, but they incessantly tripped the trigger. I never saw a bear, nor any sign of any bear. And just when I figured I might die in a bush plane, there I was trying to drown my fool self again. Sorry, Pappy.

I came around a stony point into a stiff northwest wind. Light boat and the scant fuel was far aft, jammed up against the transom. First a wave and then the wind got under the Lund and it rose and rose and rose ‘til my bear lust gave way to common sense. Almost too late I said, “This sumbitch is fixing to flip bow to stern and I’ll be dead quick in the damn Canada cold water.”

But I did not have time to think all that. I wrung the throttle back to idle and jumped with all my strength to the bow of the Lund, uphill as it was. The Lund settled down, cut a 180-degree course change just like Maggie C did when that first swell hit her off Bimini. My ribs were sore for a month, but Oh, Death Angel, I spat in your eye—again.

That was a good long while ago. I’m past 70 now and I sold my last boat, skiffs, sailboats, inboards, outboards, kayaks and canoes, first time in 60 years without one. I made Pappy that promise so many years ago and I have kept it so far. And now I make myself another: When I go to take my last drink, it won’t be seawater, lake water either.

And thank you Pappy for that gift of water and wind. Three-fifths of the world is water and the wind courses over all of it. So when you gave me that 10-foot bateau, you gave me the world, all of it, the whole blessed thing.

We’ll Do It Tomorrow: Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories by John P. Faris, Jr. is reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” 253 pages, Hardcover, Signed by the author.

We’ll Do It Tomorrow: Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories by John P. Faris, Jr. is reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” 253 pages, Hardcover, Signed by the author.