The following narrative is excerpted from Hunting Adventures in the Northern Wilds, A Tramp in the Chateaugay Woods, Over Hills, Lakes and Forest Streams, by S. H. Hammond, published in 1856. As the author travels into the back country wilderness of northern New York State, long before it is given the name “the Adirondacks,” his guide, Joe, relates the following story about a renowned old hunting guide named Pete Meigs, who takes out two inexperienced “sports” from the big city of New York, or “York,” as they called it, on a hunting trip into the hinterlands. Meigs has hired the author’s guide, who at the time was young and unproven in the woods, to help carry the camping gear and do other chores. The author’s guide addresses him as “Squire” in the narrative. His reference to a “painter” is actually a mountain lion. The hunt probably took place in the 1830s.

The next morning we were up by the dawn. Our Yorkers were fresh and fierce for the sights and fun of the woods. Everything around was new to ’em. The thousand voices that one hears in the forest were things for them to admire and talk about. We concluded to have a chase the first thing in the morning, not to run the deer into the lake, for our canoe was gone, and we couldn’t catch ’em there; so we started to drive the ridges, as we call it.

“The old man knew the woods like a book, and could always tell by the make of a country, whichaway a deer would run, when pressed by the dogs. Now, Squire, a deer has ways of his own, which a man who has lived among ’em and hunted ’em, can understand. When pressed, he will take to a ridge, and follow it till he’s tired, and then he’ll take to the water if he can, to throw off the dogs.

“Well, before the sun was up, we started out back of the lake, and old Pete stationed the Yorkers some forty rods apart, on a low ridge that stretched away from the lake, far into the woods, at a spot where he knew the deer would be most likely to pass. Having placed them to suit him, he lent me his rifle, and took me, maybe a quarter of a mile beyond, and placing me near a great oak at the head of a broad, shallow ravine, left me to lay on the dogs. He hadn’t no great notion then of my merits, as a hunter, or as a marksman, and I’ve always believed he placed me there, more to get me out of the way, and keepin’ me from spoilin’ sport for the Yorkers, than anything else, for from what I’ve learned of the animal and the woods since, there wasn’t much danger of a deer’s comin’ near me.

“‘Now,’ said he, ‘Joe understand, we’re here arter deer, and not arter partridges and squirrels, and you’re not to spoil sport by shootin’ anything short of a painter or a big buck;’ and the old man grinned and he started off with his hounds.

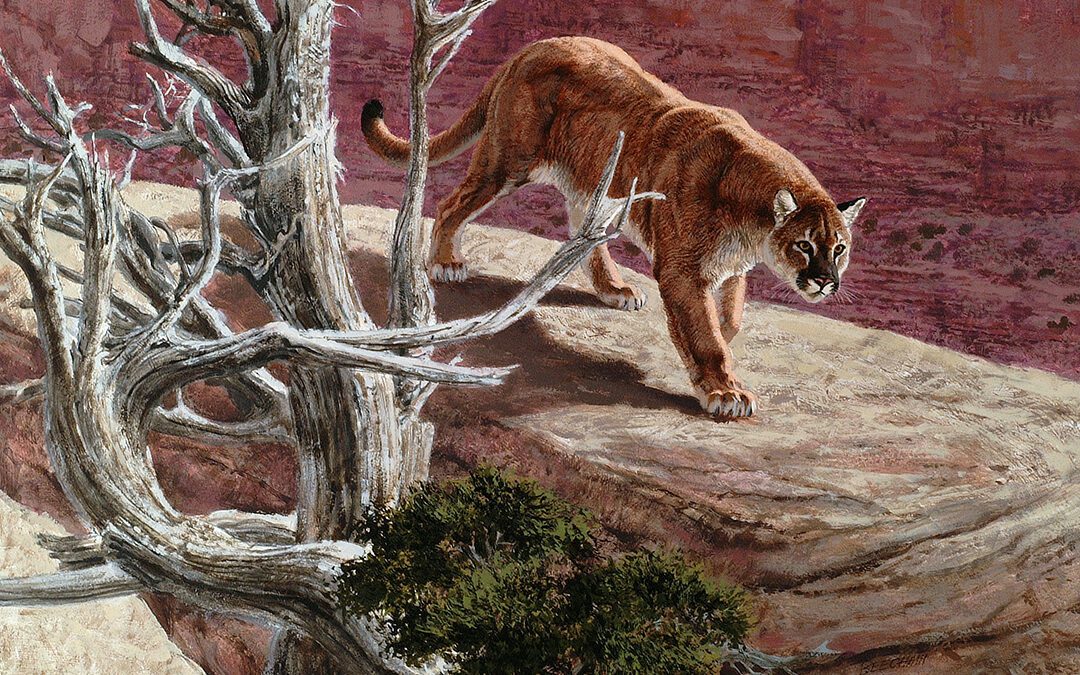

“He hadn’t been out of sight long, and I’d seen ’twas all right with the rifle, when I heard a scrathin’ like among the branches of a great oak, six or eight rods from where I was standing. Looking over that way, Squire, I’m blamed if I didn’t see laying stretched out among one of the great branches that put out towards me from the trunk of that old oak, maybe thirty feet from the ground, a great painter, lookin’ with most villainous fierceness straight at me. That was the first of these varmints that I’d ever seen alive in the woods, and the way I kinda crept all over wasn’t pleasant. I was standin’ by the side of a maple, which was partly between me and the animal, and I wasn’t sorry it was so. I don’t know as the painter meant me any harm. It’s very likely he made up his mind to let me alone, if I’d let him alone; but I didn’t like the way he eyed me. I drew up old Pete’s rifle by the side of a tree, and my hand shook some as I sighted at his head. I wasn’t fool enough to fire till my hand was steady, for I knew if it was calm, I could put a ball between his eyes from where I stood, and no mistake. I sighted him close and steady at last, and pulled. The painter leaped straight towards, and fell a few yards from me, dead, with his skull shattered from my ball. ‘There,’ said I to myself, as I fell to reloading my rifle, ‘old Pete didn’t think when he told me to fire only at a painter, or a big buck, that that cussed critter was about.’ I was a big feelin’ man then, Squire, and about the proudest one in the Shatagee country.

“I was examinin’ the beast, when I heard far off in the woods, the voice of old Roarer, deep and drawn-out-like at first; after a moment I heard it again. The time between his baying became shorter, till the dogs both broke out in a fierce, continuous cry, and I knew the game was up and away. I needn’t tell you, Squire, of the music there is in the voice of a pair of stag hounds, in the deep forests of a still morning. How it echoes among the mountains, and swells over the quiet lake; how it comes up like a trumpet from the forest dells, and glancin’ away upward, seems to fill the whole air with its joyous notes.

“The dogs took a turn away to the westward. The sound of the chase grew fainter and fainter, as it receded, until it was lost to the ear in the distance, and the low voice of the morning breeze whisperin’ among the forest leaves, alone was heard. After a few minutes, I heard, faint and far off, the music of the chase again, swellin’ up in the distance, and then dyin’ away like the sound of a flute in the distance, when the night air is still. Louder and more distinct it became, as the dogs coursed over a distant ridge.

“I stood, as I said, at the head of a shallow but broad ravine, or rather valley; to the right and left, the ridge stretched away like a horse-shoe, havin’ within its curve a densely wooded hollow. I heard the hounds as they crossed this ridge far below me, and loud and joyous, makin’ the woods vocal with the melody of their voices.

“Again the music died away, as they plunged into the hollow way before me, until it seemed to come up like the faint voice of an echo from that leafy dell. Again it swelled louder, and fiercer, as the chase changin’ its direction swept up the valley. Louder and louder grew the music; I heard the measured bounds of a deer, as he dashed up the ridge on which I stood, some forty rods from me, and wheelin’ suddenly from the direction in which he was goin,’ an enormous buck broke, with the speed of a race-horse from the thicket of underbrush that had concealed him, directly toward where I was standin’. I was ready, and when he came within a few rods of me, I fired. He leaped high into the air and fell to the ground. My huntin’ knife was soon passed across his throat, and his struggles were over. It was a noble buck. I have been a hunter ever since, and I have seen few larger than the one I shot that morning.

“In the meantime, the dogs swept by me in full cry from where the Yorkers were stationed. It seemed that two deer had been started by the hounds and had run together, until they struck the ridge on which I stood, when one had turned suddenly from his course, and the other fled forward. I heard two shots in quick succession.

“In a few minutes the music of the dogs ceased, and I knew the chase was over. I passed down to the Yorkers and found them rejoicin’ over a fine doe they had slain. Both had fired upon her—the one woundin’, and the other killin’ her. They supposed she had passed me, and took it for granted I had missed her.

“Old Pete came in. He had heard my first shot, and supposed of course, I had been firin’ at some triflin’ game. The old man joined the Yorkers in laughin’ at me. ‘Come,’ said I, as I took him by the arm, ‘go with me and I’ll show you what a hunter can do. ‘We went up to where the buck lay, and you ought to have seen the old man’s eyes open, as he rolled him over. ‘Joe,’ said he, as he held out his hand, ‘skin me if you haven’t done it. I’ve been after that buck for two years. Why he’s the one of the old Shatagee.’

“I led him to where lay the painter, ‘There,’ said I, ‘you told me to kill a painter and a big buck and I’ve done it.’

“The old man threw his arms around me, and from that time, I was to him as a son. Many and many’s the time I’ve heard him tell that story, and been pointed out by him as the man that shot the painter and the big buck.”

This article originally appeared in Duncan Dobie’s Dawn of American Deer Hunting VIII. Featuring over 375 images, it will transport you back to simpler but more challenging times when rugged outdoorsmen had to endure whatever nature threw their way and sometimes suffer mightily in order to “bring home the bacon.” Order your copy today!