“I had no idea she was pregnant,” said Skinner, who’d been trying to breed her to his accomplished retriever, Drake, for close to seven years with no luck. But when no one was looking, the seniors became parents to Duke with his ingrown tail, and a brother, whose front leg was so severely deformed it had to be removed.

“The only thing I can do is put him down,” pronounced the vet while jamming the x-ray into a lit frame to prove his point. “For some reason the tail grew internally and is wrapped around his spinal cord. Probably an injury while in utero. He has scoliosis, so he’ll probably never walk.”

While cradling the three-day-old black Lab that had yet to open his eyes to the world, Skinner could smell that sweet puppy breath. The tiny deformed blob yelped and retreated into Skinner’s chest as if disputing the charges. The pup’s life was truly in Skinner’s hands. He knew what had to be done, but couldn’t silence the nagging question from his 16-year-old son, Hunter.

“You’re not going to put him down are you, Dad?”

The troubled boy had looked up to him with overwhelming sympathy for the animal.

Skinner found a home for the three-legged male, but knew he couldn’t burden someone with Duke, since odds were better than good that the dog would eventually have to be put down. Soon as Duke opened his eyes, he seemed ready to take on the world as he dragged himself around the house. Skinner was not convinced the disabled dog would live a decent life. He prepared himself and Hunter for the worst, until the day Duke suddenly stood. Wobbling on all fours, the pup looked up at Hunter, then at Skinner—and ran! Ran across the living room, then smacked into the wall. He went down hard, but got right back up. A told-you-so smile filled Hunter’s face as he looked at his dad.

Like a truck with a bent frame, Duke’s swiftness was remarkable. His bowed back legs worked in unison like the world’s fastest bunny.

“He never slows down and he’s the most intense pup I’ve ever seen,” says Skinner, who’s been breeding and training dogs for more than 30 years at Camanche Hills Hunting Preserve in northern California where he’s an owner. His days are spent releasing ducks, pheasants, quail and chukars for members throughout 1,500 acres of Sierra foothills. He also guides hunters, which calls for retrieving thousands of birds—making good dogs a basic necessity.

Duke sports a dazzling smile whenever he’s around owner Marshall Skinner.

Unfortunately, the years were catching up to Skinner’s best dogs. They were declining with age. Although Duke was instinctively retrieving most anything he could get his mouth around, it was unlikely he’d ever be anything more than a pet.

Skinner had no notion of the hell to come and how crucial his decision to keep Duke would eventually become. Before the pup was given the chance to become a genuine bird dog, Hunter Skinner ended his own life. Like many parents of teen suicide, the dark cloud of guilt and grief that followed was nearly unbearable. Skinner dug deep and somehow found the courage to get up and go on living with what was left.

There was a comfort in the bond being forged with Duke. A reflection of the love and goodness that Hunter had to offer the world. Skinner and Duke became inseparable.

A soft yellow sun gently lifted the veil of frost from Camanche Hills as nine-week-old Duke rode shotgun with Skinner in his beat-up Toyota truck. They planted pheasants, one after another, deep into tawny ryegrass cover.

As the crisp fall day thawed, Skinner decided to let Duke explore one of the empty fields. Little Duke took off, rooted his snout below the swells of tangled grass and began snorting. Louder and louder, like a locomotive gaining speed—he seemed to be on track. Skinner doubted there were birds, but grabbed his gun just in case. Duke acted “birdie,” but with no tail—communication was difficult at best.

Within minutes, Duke pushed a big rooster pheasant into the air. Skinner shot and the bird fell into a nearby pond. Despite zero water experience, Duke dove in and swam to the struggling pheasant. But when the bird suddenly sank, the confused pup stopped swimming and disappeared under the murky water.

Skinner’s heart flapped in his chest. After all they’d been through, the thought of the pup drowning on his first retrieve was unbearable. Skinner dropped his gun, pulled off his shirt, and was nearing the shore when Duke emerged from the darkness. A wave of emotion swelled in Skinner as he stood shirtless and watched Duke claim and deliver his first bird as if he’d done it a million times.

Skinner decided to fast-track Duke and, by six months, he was a full-time hunting savant.

The dog’s I-got-this attitude was no more apparent than the day he plunged from a craggy lava bluff high above Rabbit Creek to fetch a crippled goose twice his size. Skinner figured Duke would drop the bird due to the difficulty of climbing up the lichen-pocked rocks with the cumbersome weight. Instead, pure determination fueled him as he struggled for almost an hour to drag the massive goose up the steep ledge. A bald eagle circled above—watching. Waiting until Duke dropped the gander at Skinner’s feet.

Primarily used for 100-yard-plus water retrieves, Duke turned into an amazingly fast swimmer.

“I’ve used him on extended retrieves over five hundred yards and he loves it,” Skinner notes. Or, it could be the Camanche Hills pancakes topped with gravy awarded after each and every hunt that keeps Duke eager to please and always craving more.

Now in his third year, Duke averages 3,500 water retrieves per season—he finds and flushes upland birds—and recently did three half-mile land retrieves. He catapults from the Rabbit Creek bluffs so often for extended retrieves that Skinner has lost count. Nimrods notice the dog’s disability and rib Skinner about the runt, his missing tail and funky gait, until they see him work. Skinner could cash in. Sell Duke to the highest bidder for a pretty penny, but admits he wouldn’t trade him for the world.

“He’s the coolest little dog I’ve ever seen. He’ll do anything for Marshall,” says gun dog guide, Pat Russell. “They’re devoted to each other.”

The superstar sports a dazzling smile when he sees Skinner since tail-wagging is not an option.

“Now, he does backflips when he knows we’re going hunting.” Skinner smiles, but his eyes can’t hide the hurt and well with tears. He knows Hunter would have been proud. Knows the reason he did not discard the malformed pup.

“You’re not going to put him down are you, Dad?”

Devastated and neck deep in grief, Marshall Skinner is beyond grateful to have Duke by his side.

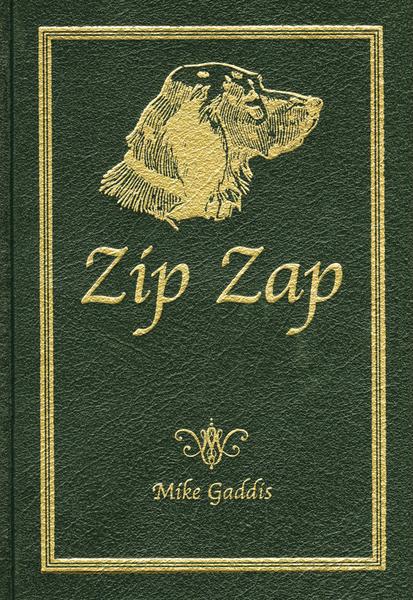

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now