For a “sporting artist” could there be a name more fitting than Bob White?

I will answer the question for you. Obviously, the correct response is: “No, there could not.” It isn’t as if this modern fine art painter and illustrator who lives near the St. Croix River in Minnesota had to invent a pseudonym to seize our attention with his hunting and fishing scenes. White’s motifs deliver all that’s required; they call out our names and when we see them, written words are unnecessary in our interpretation of what’s going on.

What may not be readily apparent is that White’s feel for the visual adventures he presents come from a rarefied place of authenticity inhabited by few other 21st century artists. White is also a legendary guide, revered even by others of that profession who lead clients on hunting and fishing trips into the wildest corners of North America.

“He’s one of the big ones out there in terms of modern sporting artists, but he wouldn’t think of himself that way,” says John Gierach, a dean of trout water writing and who has had many of his memorable magazine pieces enhanced by the presence of White’s illustrations. “Like all the best people, Bob modestly portrays himself more as being a student instead of a master. But that’s the way it is with masters who never allow themselves to believe they can’t learn more, can’t get better or that they fool themselves into thinking they know all there is to know.”

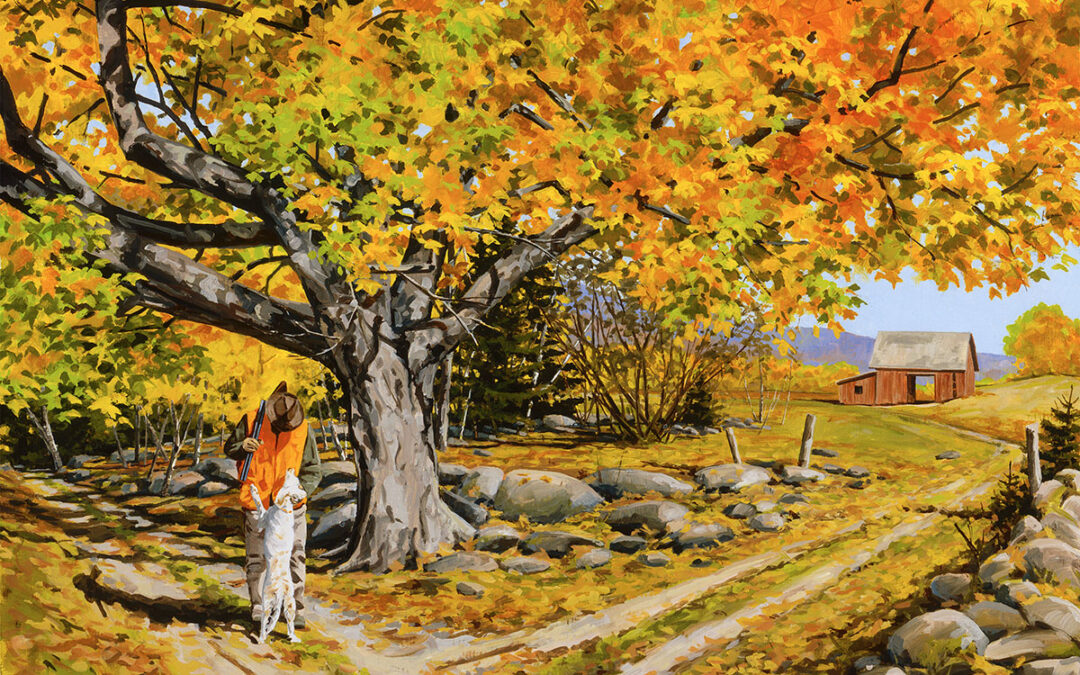

“Prairie Still Life” by Bob White

The fact is, White knows plenty, Gierach says, about the natural world and the myriad ways of absorbing its wonder then attempting to translate it through visual art or words.

“To give you an idea, Bob White is the kind of guide in Alaska who others come to for advice,” Gierach adds. “I was having a shore lunch recently with a guide and I said this looks just like a shore lunch Bob would make. And he said, ‘One of the first things we learn pretty fast is that if you want to be a good guide, you realize that how Bob approaches things is pretty much the way things ought to be done.’”

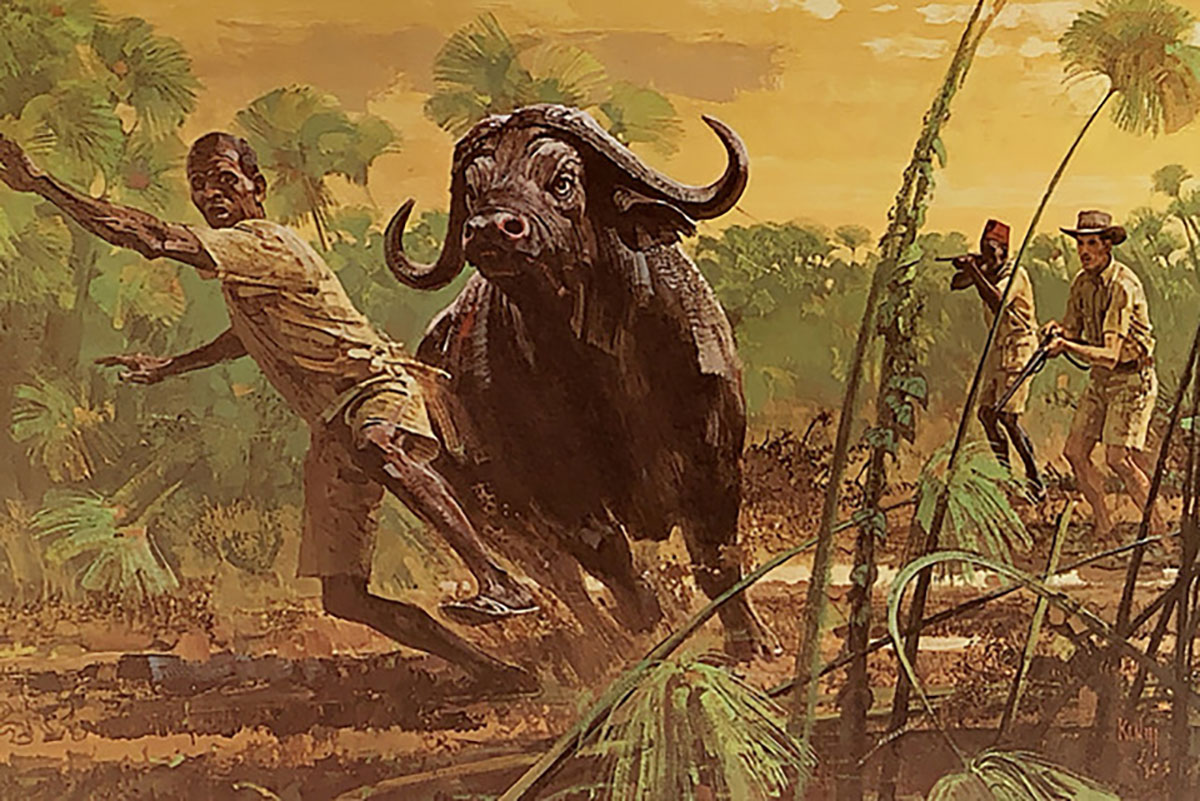

The power of White the painter is all there in the handsome coffee table book, The Classic Sporting Art of Bob White. If you’ve enjoyed the likes of — get ready for some serious name dropping — Winslow Homer, Frank Benson, Francis Lee Jacques, Chet Reneson, Ogden Pleissner, Aiden Lassell Ripley, David Maass, Brett Smith, the late Bob Abbett and Eldridge Hardie, LeRoy Nieman and dozens of others, then you’ll love exploring the diverse terrain on White’s map. Likely, you’ll experience a strong sense of déjà vu, having encountered it before in many of your favorite outdoor publications.

White grew up in southern Illinois and, as with many young people his age, in the absence of helicopter parenting. Suffice it to say, starting with his semi-feral pre-adolescent years of wearing coonskin caps, carrying BB guns and having a buck knife in the pocket, he did a lot of exploring the habitat associated with hunting and fishing. And, of course, he got his imagination piqued while pouring over classic magazines at the local barber and doctor and dentist offices. Apart from the masters mentioned above, he notes. “Two lesser known artists who strongly influenced my life were Eric Sloane and Hollings Clancy Hollings. Though not particularly ‘sporting artists,’ they were great storytellers about subjects in the natural world, and it was from them that I began to imagine that writers could illustrate their own essays, and that artists might write to the images they create.”

It’s a well-known fact that a parent’s zealous passion for anything can suck all of the air out of a space when it comes to their children and allowing them to breathe in the sublime joy of being outdoors in their own way. Many a resentful kid has been turned away from hunting, fishing and hiking by parents who forced them to do things they weren’t ready for. White’s dad didn’t do that, and it’s one of the reasons why we have White’s art.

“I was one of those fortunate kids whose father introduced them to fly-fishing and upland hunting — and the benefits of those experiences have deeply shaped my life,” he says. “My father wasn’t a duck hunter, and looking back on it, I think that’s why I became so obsessed with it. It was my personal adventure; something that I explored and taught myself. I’ve benefited immensely because of my father, but I think it’s safe to say that he wouldn’t understand the suffering duck hunters seek.”

Starving artists, trying to support themselves while also trying to immerse themselves in the experiential medium that inspire their work, have tough choices to make. “As a young man I collected old issues of Ducks Unlimited from the local barbershop. I coveted them for the artwork, which I loved, but the idea of joining the organization never crossed my mind. When I was 16 years old, a box of shot shells was $2.50. I don’t recall what the cost of a membership to DU was in 1974, but it would have cut into my hunting budget,” he says.

White studied painting, sculpture and art history in college. Then, in his senior year, he kind of panicked at the thought of what he’d do with that training. “It occurred to me that I liked to eat on a regular basis, so I pursued a degree in social work and upon graduating, moved to Minnesota to work as a therapist with adolescents and their families.”

Human services work is incredibly difficult emotionally, so White landed a job with an Alaskan fly-out fishing lodge and he’s notched 45 seasons doing that since 1984. They’ve given him plenty of fodder for written essays and illustrated artwork. It’s worth noting that in 1988 he was awarded Guide of the Year by Fly Rod & Reel magazine. He also was featured as a guide and artist on ESPN’s “Fly Fishing the World” and “Fly Fishing America” segments.

Among the talents of sporting art literature and associated art that he’s collaborated with are Nick Lyons, Gierach, E. Donnall Thomas, Jr., Bill Tapply, Paul Guernsey, Judith Schnell and, most recently, Steve Ramirez.

White started providing artwork for the DU magazine about 15 years ago. Looking back, he notes being inspired by the legendary David Maass, the Minnesota artist. “I’ve always admired his evocative landscapes and skies, which I believe are as descriptive of the day afield as any of the waterfowl painted in them,” he says.

“First Cast” by Bob White

Paintings are forest expressions of the heart. Consider the sense of gratitude that informs the work, First Casts. “Remember the guy who put up with all your knotted leaders and dodged those first awkward attempts at a back cast? Yeah, that was probably your dad,” he says. “You thought that you stood alone in the stream that day, but he was there, beside and behind you, to keep you dry if you stumbled, and coach you if you needed it.”

For White, it’s also about trying to move deeper into the mystery. A painting in this story is titled Chippewa River Nocturne—Below Wanigan. It’s a work that has never before been published and White has held onto it as his own personal meditation. “It’s a self-portrait with two of my heroes — Tom Waters, professor emeritus of entomology at the University of Minnesota and bamboo rod maker Dave Norling,” he says. “Tom crossed his last river a few years ago, but Dave is still with us, and still producing some of the finest bamboo rods around.”

It can be a tricky thing, however, communicating the language of nostalgia without being overly sentimental or allowing the imagery in a painting to become kitschy, like a bad greeting card. “I believe that when an image prompts sensory responses beyond just the visual it can elicit memories and communicate nostalgia without becoming overly sentimental. When a painting causes the viewer to feel, for example, the bitter cold of wind-driven snow, hear waves pounding on a rocky shoreline, taste the tang of a salt marsh or smell the ripeness of a cedar swamp at dusk, then the image is transformative; transporting the viewer back in time to a memory,” he explains.

“When someone views a painting and says, ‘I know that feeling, I’ve been there,’ then the artist has gotten something right.” Winslow Homer nailed it. A painting when done well summons not merely a singular moment but it provides a window into re-savoring the entire experience.

Here, White riffs on what he means: “A waterfowl hunter might spend hours on the road driving in the dead of night, then spend a pre-dawn hour poling out into a marsh, gathering marsh hay around himself and his retriever to stay warm when an unexpected squall rips through. Then freezing his fingers while recovering decoys that are iced over; dragging his canoe out of the marsh because it’s too windy to paddle, and when he finally gets home, perhaps — if he’s lucky — hanging a duck or two under the eave of the back porch and watching them twist in the wind on his lanyard,” he says. “Of course, there was that instant when he rose in the blind, stiff with cold, swung on a pair of birds and pulled the trigger. But that represents such a small part of the experience, and it’s not necessarily the way it’s remembered. I’m more likely to paint any of those ‘other’ moments than a hunter rising for the shot.”

Donnall Thomas, friend, outdoor writer and collaborator with White, observes, “One element missing too often from sporting art is intimate knowledge of the subject. Bob White’s work makes it obvious that this is not an issue for him. Bob has been there and done that, always with his eyes open to the visual nuances of the hunting and fishing world. His ability to capture light is unequalled, and his unique style often makes me see outdoor settings more clearly than I saw them when I was there,” he says. “Bob and I have worked together on numerous magazine pieces and being asked to contribute the prose introduction to the “Wingshooting” section of his recent coffee table book was a real honor. I refer to his art frequently when I am searching for just the right words to convey the sense of a special place.”

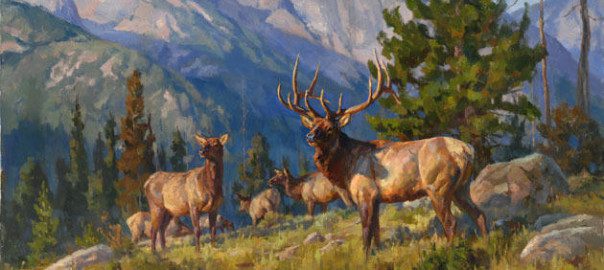

“The Last Day” by Bob White

When White paints a landscape, a rendering of a sporting environment, he’s as likely not to paint a person into the scene. He would rather have viewers place themselves in the picture. “I feel that a landscape without a participant allows the viewer to more easily insert him or herself into the scene than one in which there is a sportsperson present, in which case they are relegated to the role of voyeur.”

All of us have contended with that bittersweet feeling that comes with the biting cold advance of winter and the end of another hunting season. White explores it in his piece, The Last Day.

“Years ago, I made a pact with myself to go hunting the last day of the season, no matter what the conditions,” he shares. “I’ll go, even if I have to walk across a frozen river to find an open spring hole to float my decoys. It’s a good excuse to spend time with myself, and I usually bring home a duck or two. It’s also the opportunity for soul-cleansing solitude.”

“Color and Light Reflected—Brown Trout” by Bob White

White is also endlessly fascinated by the luminosity of fish, which is explored in Color and Light Reflected — Brown Trout. “He was so beautiful and the light so perfect that I decided to take some photographs. But I knew the instant I took the shot that the reflective quality of the fish and the wonderous patterns of color and light in the water would inspire a painting,” says White.

The Classic Sporting Art of Bob White features 200 images in oil, watercolor, pencil and ink of fresh and saltwater fly-fishing, upland and waterfowl hunting, game fish and birds, sporting dogs in field and portrait and landscapes from Alaska to Patagonia. The book is a feast and yet it’s only an appetizer. There’s nothing like seeing a White original, which is nearly as impactful as living the moments that inspired it.

With clean-finished seams, single chest pocket and buttondown collar, it has all the makings of your favorite dress shirts. It’s treated to fight wrinkles and stains. Plus, it comes out of the dryer looking neatly pressed and ready to wear. Embroidered with “Sporting Classics Patron” in gold thread above the pocket. Shirt made by Lands End. Buy Now

With clean-finished seams, single chest pocket and buttondown collar, it has all the makings of your favorite dress shirts. It’s treated to fight wrinkles and stains. Plus, it comes out of the dryer looking neatly pressed and ready to wear. Embroidered with “Sporting Classics Patron” in gold thread above the pocket. Shirt made by Lands End. Buy Now