Some of these men returned safely, but many others who sought the “white gold” … would die in the process.

When the ruthless King Leopold II of Belgium died on December 17,1909, so did the severe restrictions on hunting the King’s elephants in the Lado Enclave of the Congo Free State (now southeast Sudan and northwest Uganda).

King Leopold had ruled from an annexed throne and made the Lado Enclave his own personal domain to do with as he wished. After his death, the district became a no-man’s land until the Belgian and British Royals could decide who should control it.

This meant the area was open to hunters who could bag as much ivory as they could carry out. The only obstacle was the large number of loyal Belgian askaris who remained. They were a disorganized bunch of dangerous savages who did not hesitate to shoot on sight.

Soon the “ivory rush” was on and, despite the risks, hunters from all corners of British and German East Africa raced to take advantage of it. Even Theodore Roosevelt made a point of going to the Enclave that December (1909) before completing his safari. Although the President went there for white rhino, not elephant, it was really to meet the poachers.

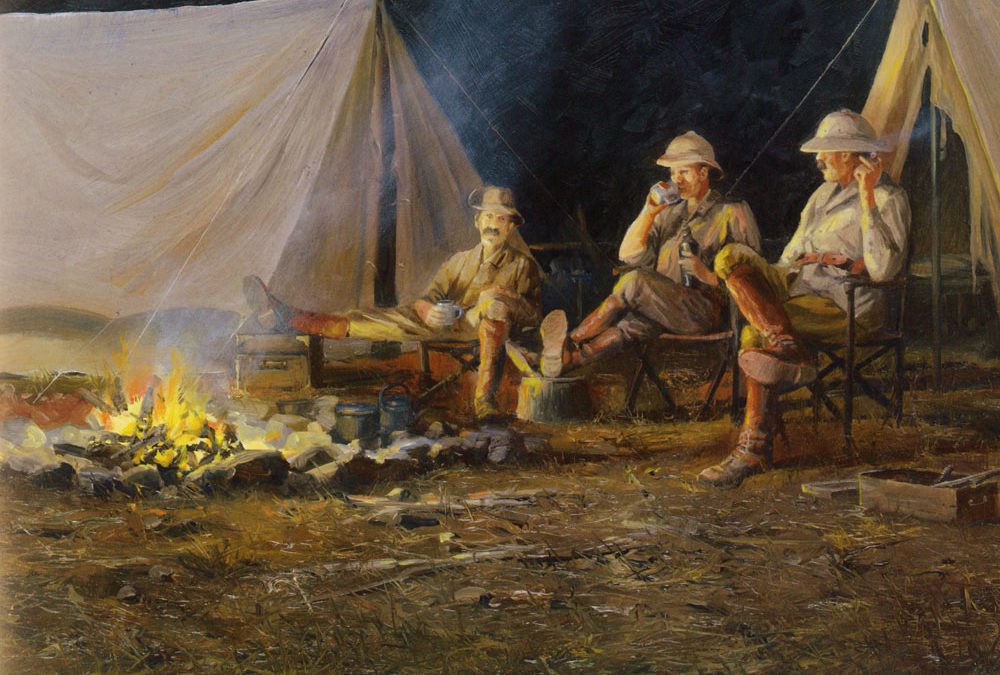

TR referred to the men who flocked there as “a hard-bit set,” but affectionately called them “a company of gentleman adventurers.” In reality, they were nothing more than poachers raiding an unadopted territory of its ivory resources before some authority could put a stop to it.

The situation in the Lado Enclave would last only about nine months, until the district became a province of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan with the southern half being controlled by the British Colony of Uganda.

In the meantime, some of the most prominent hunters of the time went to the Enclave in search of the big prize: huge herds of elephants, some containing as many as 500 animals, and bulls carrying ivory up to 200 pounds per side.

Some of these men returned safely, but many others who sought the “white gold,” particularly the lesser known and inexperienced, would die in the process. One such hunter was William Pickering, who literally lost his head doing it.

A well-known poacher and extremely good shot, Pickering was charged and killed by a bull elephant. It seems that he froze with his gun raised as the elephant bore down on him. The huge beast ripped off Pickering’s head and then stomped the man’s lifeless body into the ground.

For most hunters, however, their biggest challenge was outwitting the Belgians and getting themselves and their ivory safely out of the country. The British were sympathetic to the poachers, as it wasn’t “their” ivory, and they benefited from a 25 percent tax on any ivory brought into the British Protectorate from the Belgian side.

One ingenious deception was orchestrated by famed elephant hunter Bill Judd when trying to get across the Nile with a huge haul of ivory. Local natives told him that a Belgian patrol was hidden atop a hill watching the swamp he had to cross to reach the Nile. His only chance was to create a diversion.

He arranged to have some wooden poles whitewashed with the clay used on the inside of native huts and then divided his pagazi into two teams. He went with the group carrying the white poles, which drew the patrol down the hill while the real ivory went ’round the other side of the hill and made it safely across the Nile. It’s ironic that it was an elephant that would end Judd’s life years later (see “Last Safari”).

Robert Foran hatched another ingenious ruse. This was the same Foran who acted as correspondent for the Associated Press, while unofficially covering the Roosevelt safari a year earlier (see “Codename ‘Rex'”).

The former policeman decided to sneak ivory over to the British side under the cover of a moonless night. He hid his heavily laden canoes along the bank on the British side, then at daybreak he and his men paddled the ivory, as though being chased, back to the Belgian side where they pretended it had been poached in the British territory.

Happy to get one over on the British, Belgian officials agreed to buy the ivory from Foran, who made a handsome profit on the deal, all tax-free.

There is no doubt the activities that took place during the Congo’s transition did much to enhance the frontier atmosphere of early East Africa and the legends it spawned.