It tumbles off the east face of Big Back Mountain, leaping and flowing down its stony, laurel-lined course as it has for eons. Dad and I had fished its lower reaches when we’d first moved to Tennessee back in the early sixties, and many times we had talked about someday fishing all the way up to the big granite boulder we’d heard about that was supposed to give birth to this little spring-fed creek.

But with Dad gone, I hadn’t fished the stream for years, and even then I’d never been above the flat nearly halfway up the mountain that the locals call Frog Level.

The old gentleman who first told us about the creek had shown us an ancient, faded photograph of himself as a boy with his own father, standing with three coonhounds beside the big rock that he said sheltered the little spring that gives the stream its birth. But we knew from experience that he was sometimes mistaken about such places and events, and so we weren’t at all sure that this was actually the source of Cole Creek.

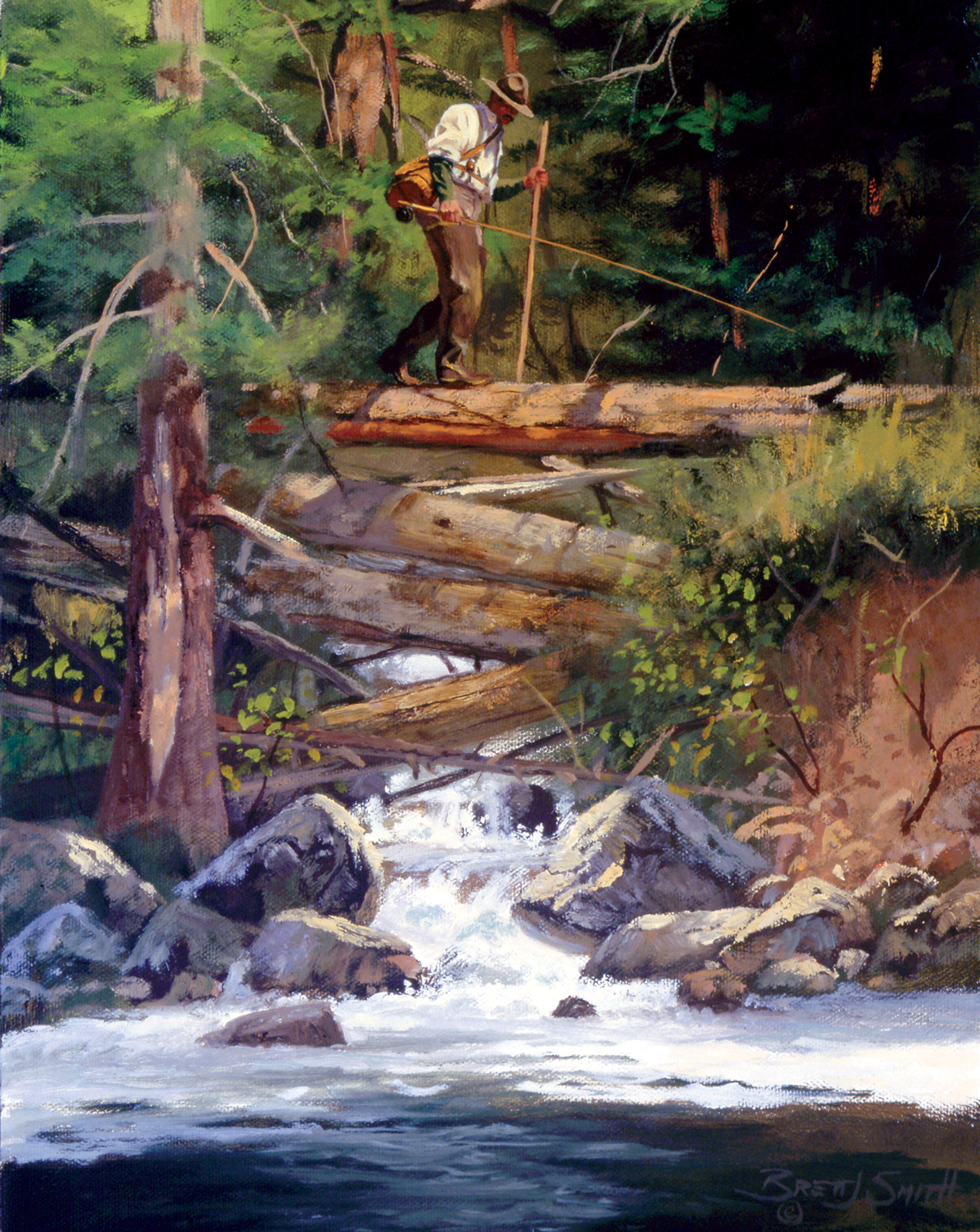

On a cool April evening approaching midnight in my 51st year, I decided it was finally time to fish Cole Creek all the way to the top. My fly fishing gear is always ready for such late-night or early morning impulses; so at five o’clock on a crisp Saturday morning I stepped out into the starry night and struck the narrow trail up the mountain as the first faint rays of daylight began feathering the sky at my back.

Firmly focused on finding the big source rock before the day was done, I eased quietly along the darkened trail beside the lower reaches of the stream for the first mile or so as the birds began to awaken around me. I knew these lower waters well from decades of fishing them, and when I came to the low and angular rock shelf that holds back the high grassy meadow along the outer edge of a long-familiar bend, I made my first cast of the morning.

I had rigged my fly rod the night before just for this run, for it was here where I had caught my first trout on Cole Creek over 40 years ago. Now I swung my little streamer deep along the rock shelf as I had swung it then, and a fat little rainbow hammered it within three feet of where its ancestor had taken my fly as a boy.

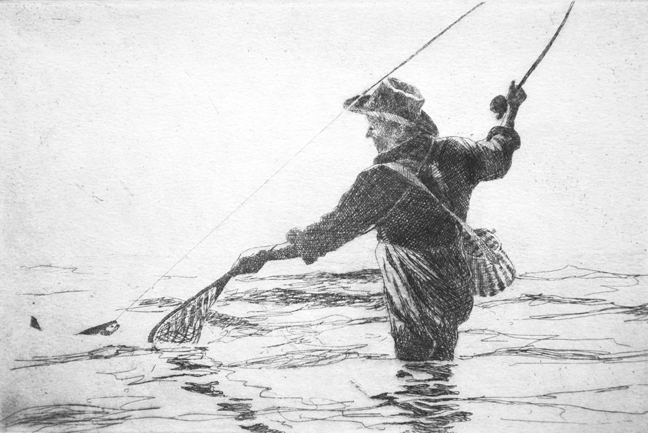

The trout pivoted in mid-air and dove deep beneath the edge of the rock and shook its head in vehement protest of this interruption to his morning routine. When I finally convinced him to join me for a moment, I slipped my net around him only long enough to remove the little barbless hook from his lip and apologize for the intrusion.

The next two trout also came from old familiar runs, one beneath the roots of an ancient hemlock growing along an outer bend, the other next to a boulder that split a seam where the current edged around a shelf of stone that nearly cut the creek in two. Like the first trout, both of these were around 11 inches, and both were cleanly hooked and quickly released back into the morning.

The next three trout came on a #16 green-bodied elk hair caddis, for the creek had now changed from the familiar extended pools and bends that define its lower reaches to more stair-stepped pocket waters, offering drifts that averaged at most only eight or ten feet. Two were rainbows and one was a small brown, and all were fat and healthy. I hoped there would be more browns as the day progressed, for I dearly love the colors of fish like these from little high-mountain streams. Perhaps I would even find brookies as I worked into the unknown upper reaches of the creek.

I certainly hoped so.

Somewhere I passed into virgin territory, at least for me, and now I was becoming the boy I once had been, feeling the same anxious excitement I’d felt back when I had first fished this little creek with my Dad, along with the same exhilaration I always feel when I find myself on new water with an old fly rod. I cast short beneath a dark cut to my left, gave a quick upstream mend to clear the laurel and struck too soon as I saw a swirl of color coming up from the depths toward my caddis.

It took just long enough to find and disentangle my fly and leader from the overhanging limbs for the trout to reorient itself to its lie. Easing back into position, I was determined to control my nerves and this time wait for the strike.

My first cast was far too tentative. But the second cast landed perfectly, four feet above where the trout had just risen. The little caddis drifted through a tiny dapple of sunlight where I expected the trout to rise, but it failed to appear. And just as I was about to lift the fly from the water, the fish rose daintily at the tail of the run and sipped it in.

I struck lightly but firmly and she immediately swirled for the dark depths beneath the overhang, nearly entwining my leader with the laurel. I prayed she wouldn’t jump. Quickly I bowed and lowered my little six-foot wisp of graphite to the left, and in response she turned back into the main flow.

She rippled dark green and crimson in the morning light, and I finally knelt in the stream and tucked the little rod under my arm as I slipped my hand beneath her. I eased the tiny hook from her lip, and as I released her, she slashed the surface with her broad square tail and dove for the depths.

Still kneeling in the edge of the current, I looked up and around and thought of just how unique an experience this was – to be fishing a stream I had known since childhood, yet fishing it as I had never fished it before. I stood and eased to the bank, leaned my fly rod into a clump of laurel and then dug a biscuit and flask of water from my side pouch. I then stretched out against an old hemlock and enjoyed a slow, leisurely breakfast and a quick morning nap.

The stream began to narrow perceptibly as its angle of decline became steeper, and its character began to make a subtle change as I and the sun climbed higher.

I added a little weighted Black Gnat with clipped hackles to the caddis on a light 16-inch dropper, catching one trout after another as I progressed.

They were still mostly rainbows. But a few more brown trout now began to show up, and I wondered again if I might find the little native brookies as I neared the headwaters still high above.

Some of the trout continued to take the caddis, but most of them now took the Black Gnat, and as I moved higher and the creek became narrower, I removed the dry fly entirely and retied the little weighted nymph straight onto my 6X tippet.

Somewhere morning turned to afternoon and the light started to change, and I noticed the temperature beginning to drop dramatically as the sky lowered and dark clouds began creeping over the ragged ridges above. Mist began to feather the air and my visibility dropped perceptibly, and for a moment it began to rain.

Then to my utter delight, the raindrops turned to big white flakes, and for a few minutes I was enveloped in a classic high country snow shower that lasted just long enough for me to pull my old wool sweater and raincoat from my day pack.

The snow ended as quickly as it had begun and the sky cleared rapidly, leaving the entire landscape bathed in a rich, golden afternoon glow. I had continued fishing, even with the falling rain and snow. And now as the sun broke free above me, the first brook trout of the day took my little nymph deep beside a submerged tangle of roots.

I dipped my rod tip to the surface and applied as much pressure as I dared to ease him out into open water. I could feel him shaking his head, but within a couple of minutes he was securely in my net, where I held him until I could work the fly free and release him.

With the sky clearing and the mid-afternoon sun edging toward the west ridge still high above, the temperature slowly began to rise.

My next two fish were browns, the largest of the day so far, and I slipped them into my creel with eager thoughts of supper when I returned home at day’s end.

I continued to climb, fishing as I made my way higher. From this point on, all the trout were brookies. Some were mere fingerlings and some were as long as nine or ten inches, quite large for these high mountain streams. The ridges on either side of the creek were beginning to steepen noticeably, but the angle of the water started to flatten out and the creek began to widen as it bent around the base of a hundred-foot cliff.

Then suddenly I found myself facing a long, open cut through the very spine of the mountain, with a deep, inviting run stretching out before me and the afternoon sunlight glinting off its rippling surface.

I stopped and tied on a nine-foot leader with a #14 yellow-bodied Stimulator at the end of a new 18-inch piece of 7X tippet. After the tight quarters of the last few hours, it was pure bliss to make a long, sweeping cast up through the slot, where the fly eased lightly into the top edge of the run without so much as a ripple and began dancing down the outer seam of the current toward me.

The old brook trout came to dinner like a kid at Thanksgiving, and as I struck he dove deep. But soon he burst high into the air, the spray from his leap backlit by the late-afternoon sun, then headed deep once more, holding tight to the current for all he was worth.

Even from so far downstream I could tell he was a magnificent brook trout, for the sun that had lit up the spray from his leap had lit him up as well. I began working my way up the left-hand edge of the creek along a shallow underwater ledge, hugging the rock wall at my shoulder as I went, trying to gain every foot, then every inch of line I could gather back onto the reel.

Now he turned and began moving downstream. I did not want him to get below me, and so I turned myself and carefully retraced the steps along the narrow ledge until we were once again nearly even with one another.

He found a new lie and held there long enough for me to cross the creek below him and then work back upstream against the current. I came in from below, and when I was in position, I lifted the rod tip, hoping to position him for the net. Now for the first time he saw me, and he suddenly seemed to comprehend what was happening and tore away again, back out into the long main run, taking fifteen yards of line with him.

He was by far the wildest, most beautiful brook trout I had ever seen, and his panicked response to his unnatural constraint was worthy of the most ferocious chinook salmon I ever hooked in Alaska. Again he shredded the silver surface of the pool and then leapt so high that he nearly brushed the overhanging rhododendron along its near edge before arching back into the water. I tried to bring him in quickly so as not to tire him any further and was finally able to reach him with the net. He was still surprisingly fresh, and I quickly removed the fly that hung lightly from his lower lip, all the time keeping him in the stream. I held him there for a minute or more, making absolutely certain he was fully revived before sending him back to his watery lair.

The moment was perfect, and with the afternoon waning I briefly considered abandoning the idea of fishing all the way up to the source of this wonderful little stream.

But no, I wouldn’t give up now, for was this not why I had come?

And so I eased farther upstream and around the bend where I could see that this was indeed the last long run, for here the little creek narrowed once more and began to ascend more steeply toward the deepening late-day sky. I paused and shortened my leader and switched back to my little Black Gnat, for the water had now grown tight and narrow.

Moving lightly and swiftly from pool to stair-stepping pool, I continued to fish as I climbed. I could see the north and west ridges converging to a true summit, now only a few hundred feet above, and I knew that the Source Rock, if it was real, had to be getting close.

But was it real? Did it actually exist as the old man had told us so long ago? Or was it just a figment of his fertile imagination – a good story to be sure, both for himself and for us, but a story nonetheless?

I wanted to believe it, just as I wanted to hurry, to finally find the truth for myself. But even more I wanted to fish, alone here in this most perfect of moments with nearly the entire mountain now beneath my feet.

The warm evening light and the presence of brook trout made the moment far too compelling to hurry. And so I continued to dip my little fly into each riffle and pocket and pool as I moved higher. Another brookie struck and I missed him, and three runs higher yet another one hit and I hooked him well and played him into a little side pocket where I lifted him from the water only long enough to work the fly from deep inside his jaw with my hemostat, then held him in the clear current until he finally realized he was free.

Three more pools and three more trout, all brookies; and now I too am finally and completely free. Even the looming lateness of the hour is not enough to diminish the lightness of my spirit, and I continue casting as I move upstream.

My fly rod is weightless and seems to do its work all on its own, leaving me free and unencumbered to internalize the experience. The fly line moves effortlessly low above the water’s surface, close beneath the overhanging laurel and rhododendron in short, tight loops that cast after cast deposit the fly lightly onto the narrowing stream’s surface.

The last trout of the evening hits in a little oxygen-rich plunge pool at the base of a narrow two-and-a-half-foot waterfall and then makes the grand tour of the tiny pool as he fights to free himself. Not at all content to confine his efforts to his known element, he leaps high into the cool late-evening air, hanging for a moment in a low wisp of sunlight before arching back into the water. Twice I fail to get the net into position, but finally I am able sweep it around him and watch with delight as the tiny hook falls free. I am careful not to touch him, but instead hold the rim of the old wooden net even with the surface for a moment until he manages to right himself.

Then I lower the net deep into the water and out from under him and smile as he darts away.

Kneeling in the tight confines of the tiny stream, I look around and then glance up toward the burnished sunset sky hovering out in front of me. And there I see it. A great backlit monolith of pure pink granite, perfectly haloed by the sun setting directly behind it. I stand and slip the point of my fly into the hook-keeper of my reel and wade the final 40 yards upstream to source of my dreams.

I slept alone by the rock that night.

Jane and Carly were in London, and there was no one to miss me or worry if I failed to make it home on time. I built a small fire and cooked the two trout I had kept earlier over its glowing coals, adding wine and lemon and the few choice seasonings I always carry in my little pack. I had a salad of fresh-picked watercress from the spring and drank from the clear sweet flow coming from deep beneath my host rock.

During the night I was occasionally awakened by the soft scurrying sounds of some of the local residents, some curious, some small, some not so small, as they eased past on their nocturnal errands and paused to drink from the living water we all temporarily shared.

In the morning I awoke to a coral sunrise, arose from my warm bed of hemlock and spruce, washed my face, dug breakfast from my pack, then slipped a small granite pebble into my coat pocket and turned and fished my way back out to the sunlit world below.

Note: A Cole Creek Diary is one of 34 chapters in Michael Altizer’s The Last Best Day – A Trout Fisher’s Perspective.