What compels hunters to enter into difficult, even life-threatening situations? Dangerous terrain, fierce winds and bitter cold are never fun, yet many hunters not only accept these hardships, they’re challenged by them.

The mountain climber’s answer, “because it’s there,” falls short. There’s more to it, much more than this space allows. But most hunters would agree that by persevering in the face of tough conditions, they experience life on a different, shall we say, higher level.

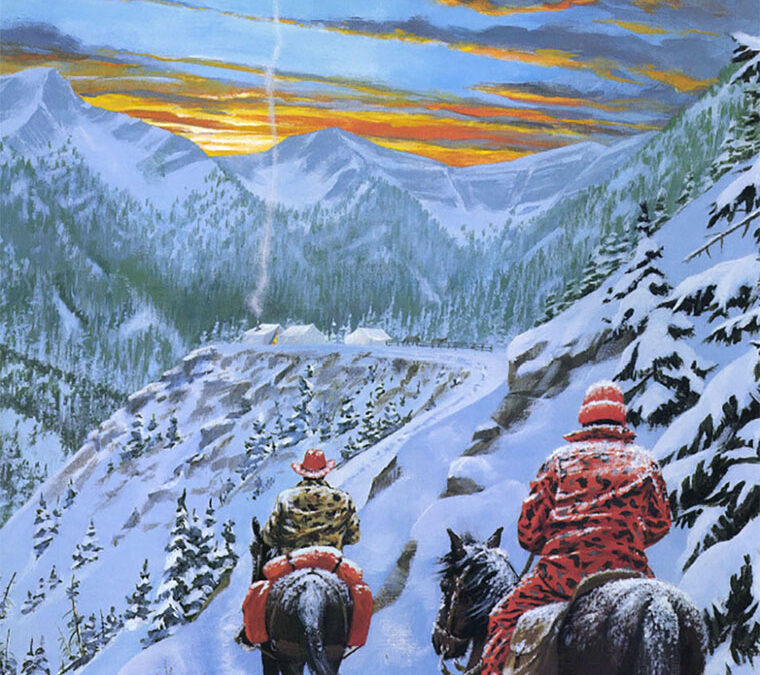

There are times, of course, when the severity is not seen beforehand. Such was the case one pleasant mid-December morning near Cody, Wyoming as we rode out on the first day of a weeklong hunt for elk. It didn’t take long before the horses were plodding through two feet of fresh snow. Somehow the guide’s horse ferreted out a trail beneath the deep drifts, but then he’d been over it before. I hadn’t. With only my toes in the stirrups, I shifted my weight toward the upslope side, figuring that if my horse slipped, stumbled or fell, I could roll off and save myself from a 200-foot freefall to the river below.

Another reason that only my toes touched the stirrups was my over-sized pac boots. “I won’t take you up there without pacs,” Charlie, my guide had said the previous evening when he saw my insulated leather boots.

“They’re well waterproofed,” I maintained.

“No! It’s just too cold up there. Your boots will thaw by the fire and soon your feet will be wet. You won’t be able to leave camp.”

So instead of riding out early, we had waited for the store in Cody to open. I bought a pair of the largest felt-lined, rubber-bottomed Sorel boots I could find. It was one of the best investments I’ve ever made.

Our little pack train continued along the south branch of the Shoshone River, climbing toward the high country east of Yellowstone National Park. Charlie explained that elk, turned back by hunting pressure around Jackson Hole, were migrating east around Pinnacle Peak. “They’ll cross the river at Pinnacle Creek,” he said confidently. “It’s the only place they can get across the gorge. We’ll hunt there.”

Wyoming game officials had authorized the late hunt the previous year. Few knew of it except Charlie, who had guided me on an unsuccessful hunt several years earlier and being the conscientious type that he is, was bound and determined to get me a bull. We wouldn’t see any other hunters, but we should see lots of elk, Charlie predicted.

Higher and higher we rode. With each hundred feet of elevation, the cold intensified. I wrapped my neck with a wool scarf as big flakes swirled down through the heavy overcast. During five hours of riding, I hadn’t seen a level spot big enough for a tent.

The horses plodded on, up and up, and as darkness closed in I realized, this hunt must be taken seriously. I’d come to formidable country, made even more dangerous by the time of year. Then, just around a bend in the canyon, I saw a thin column of blue smoke drifting into the leaden sky. Minutes later, we rode into camp.

It was a foreboding scene. On a couple of acres of relatively flat land stood a long-abandoned cabin, most of its roof collapsed. Nearby were two low-wall sleeping tents and a large cook tent, all with chimneys. At least we’d have a chance to get out of the cold.

I pulled my snowy duffel and sleeping bags from the pannier and chose a mattress in one of the tents. The mattress was only two inches thick, but it and the tarp beneath it would insulate me from the frozen earth; padding for comfort was a secondary consideration.

While wrangler Joe fired up the sheep-herder stove, I found an empty feed bag to cover my rifle, which I learned to leave outside the tent. One morning years earlier, I saw a hunter disarmed after he’d taken his rifle into the tent, where moisture from breathing condensed on the cold metal. The bolt froze in the receiver.

In the warm cook tent, coffee and conversation flowed hot and heavy. Both the cook and wrangler complained of the bitter cold. I grew even more concerned. They’re natives, I thought. How’s this Texan going to cope with these conditions?

Joe had a bad cough and looked a little ashen. Still, he insisted on taking me to the river, where we found the fresh tracks of a crossing herd. At dusk, I sat behind a bush, while Joe rested on the snow. “Go on back to camp, Joe,” I urged. “Naw, I’m okay. It’s just a cold.” He refused to leave, even though we sat there for over two hours.

I slept well that evening, though the temperature in our tent plunged nearly a hundred degrees. The stove had us toasty warm while we undressed and slid into our sleeping bags. Then the fire slowly died, and our tent assumed mountain-top temperature — somewhere near absolute zero.

When I first felt the stabbing cold, I zipped up my goose-down mummy bag. When I felt it again, I pulled the pucker strings, drawing the down snugly around my shoulders and face. I awakened a third time, cold again, reached out and flipped my summer bag over me. It had half as much down, but kept me warm enough so I was able to sleep comfortably. Each night my two tent-mates covered their sleeping bags with clothing — jackets, pants, sweaters — anything for more insulation.

Long before sunrise wrangler Joe arrived with his dog to build a fire. The dog awoke me by stepping across my legs, then snuggled against my goose down, while Joe started the fire with kindling — just splinters because of the thin air.

“Dog,” as he was called, came from casual breeding, but he showed champion behavior, will and devotion. The wrangler and Dog were inseparable. One day I watched Joe cross the river on horseback. Dog edged out on the ice, hesitated, then jumped in. The current flowed so fast that it carried the little animal about 20 yards downstream before he climbed out of the slush, shook and ran eagerly after his master.

My big horse hated crossing the river, and he’d invariably balk ’til my heels on his belly finally persuaded him to move. The thick ice would support us well out into the stream, then we would suddenly plunge through into water that came up to his knees. The experience was unnerving, because I’d never ridden across ice before and there was always the danger of the horse slipping before we broke through.

My big horse hated crossing the river, and he’d invariably balk ’til my heels on his belly finally persuaded him to move. The thick ice would support us well out into the stream, then we would suddenly plunge through into water that came up to his knees. The experience was unnerving, because I’d never ridden across ice before and there was always the danger of the horse slipping before we broke through.

That morning we put away a high-cholesterol breakfast while Joe saddled the horses. He looked worse, and coughed more than he did the night before. We all felt he should stay in camp and argued with him until he finally agreed.

It was still dark as Charlie guided Mitch Murry and me up Pinnacle Creek through a dense stand of pines and then into low scrub-oak higher up. Charlie and Mitch dropped me off, then rode around to the back side of the mountain, trailing my horse.

In pale starlight I climbed the south side, high enough to see down through the trees. I kicked snow off a rock and sat down, warmed by the climb. I glassed my field of fire, estimating distances below and across the deep canyon.

My peace and comfort were short-lived. With first light, Pinnacle Canyon became a wind tunnel and I quickly realized why tall pines didn’t grow here. A cowboy once showed me how to tie a neckerchief around your face to protect it from the wind. I tied on a wool scarf the same way and it provided a good barrier against the stabbing cold. My 32-ounce wool pants, thermal underwear, wool sweater and down jacket had never failed me, and I was confident my feet would stay warm inside my new pacs. I wiggled my fingers and stressed my arm and leg muscles with isometrics, but if any heat was generated, I couldn’t feel it.

Light came slowly. I studied the trees below, looking for brown elk against white snow in the black forest. Before climbing, we’d seen fresh tracks; elk had moved up the valley during the night. I watched, waited and shivered.

Soon I needed relief from the cold. I wanted to escape the wind by moving down into the trees, but I wouldn’t be able to spot much from there. Also, I needed to see Charlie and Mitch when they rode back. Walking to camp was out of the question — too much snow and a river to cross on foot. I knew I was losing body heat rapidly and I began to think about hypothermia and how long it took to lose one’s senses.

“You damn fool,” I said to myself, almost out loud. “It’s in the game bag.” In my jacket’s game bag, I kept a saw and a Space Blanket for emergencies. The blanket of thin plastic had a silver reflector surface on one side. Wrapped in it, one couldn’t freeze. I’d carried it for years and never needed it. With as little motion as possible, I draped the plastic over my windward side and tucked it underneath me. I still shivered a bit in the swirling cold, but I felt secure.

From my lofty vantage point, I watched the treetops bend and heard the forest moan in the swirling wind. Being alone in harsh conditions can be a profound experience, one that entices men into all kinds of chancy ventures. My awareness heightened to a feeling of total comprehension — a sensation of thrill. Knowing that my life depended on my clothing and gear which I’d carefully selected and tested many times, I felt almost a friendship with them. In control and totally self-responsible, I found myself enjoying the “edge.”

My reverie ended sometime later when I saw motion below: Charlie, Mitch and my ride back to camp. Obviously, the elk had bedded down out of the wind. We headed for our hot stove.

Joe had been sleeping on a small cot in the back of the cook tent, but he awakened to our voices around the lunch table. I wanted to know his temperature. No way. No thermometer. Even in the warm tent, my hands were cold, so everyone’s forehead felt hot. And, Joe’s cough still rattled. He slept the rest of the day and through the night.

The next morning, Joe was up building fires and saddling horses. “He’s a hard man, who’ll do his job come hell or high water,” Charlie said. Obviously, Joe was pushing himself. His cough had not improved, and pneumonia came to mind, a deadly serious illness which can develop quickly. With pneumonia, the lung membrane thickens, slowing the passage of oxygen. I worried that at this altitude, with less oxygen, even a little pneumonia could be fatal. Though not complaining, Joe readily agreed to stay in camp. And, the horses were ready.

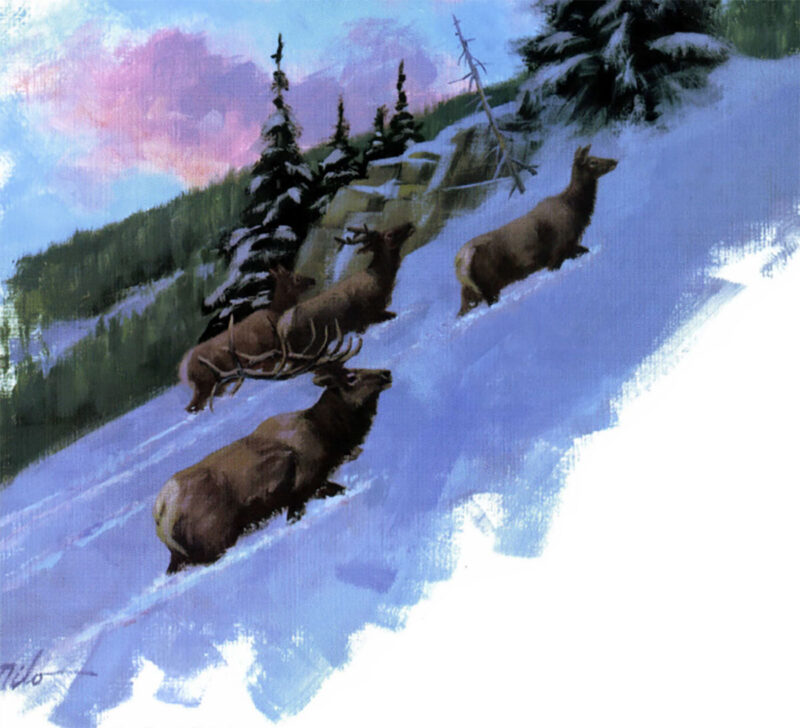

Shortly after dawn we spotted a small herd of elk, among them a big bull. They saw us, too, and raced up the mountainside. Not knowing the country, the herd moved into a pocket with sheer rock walls on three sides. Though high above us, they were trapped.

I slid off my horse, pulled my rifle from the scabbard, sat down and leaned back into deep snow which held my body like a rock. I used the sling to steady my Winchester 70 and I began scanning the elk as they milled about. Finally, I managed to scope the bull Charlie had been almost yelling about.

By now, my bare right hand was aching from the cold. I didn’t know how to hold, never having shot at such a steep upward angle over such a long distance. The longer I studied the elk and steadied the rifle, the more my hand hurt and my fingers got so cold they lost all feeling and function. Still, I managed two shots, both misses.

I decided to pull on my down-filled glove, even though I had never fingered a trigger through a glove so thick and wasn’t sure that I could. With the rifle on safe, I barely squeezed into the trigger guard of the 338 Magnum.

“Just barely over him,” Charlie exclaimed after my next shot. The glove cost me lots of feel, though I felt some degree of control. My timing suffered, but the squeeze was soft. Shooting habits developed from long hours of practice paid off; my next bullet hit.

The bull staggered, fell, and tumbled down the slope before hanging up on a jagged rock outcrop, still high above us. If my bullet hadn’t killed him, the fall onto the rocks probably would have. We struggled up to the fallen animal, wading through waist-deep snow over a layer of slippery rocks. He’d fractured his jaw, but the antlers were intact. Blood showed a chest hit, and while field-dressing the animal we found a bullet hole just above the spine.

Getting the big five-by-five down the mountain proved dicey. Free of any obstacles, the carcass would slide or roll easily down the steep slope, and once moving, it could crunch one of us against a rock or tree as we tried to steer its descent.

That morning the wind died and the elk started moving. Back at camp, Mitch’s grin reflected his first elk after years of trying and he was feeling exuberant. Joe said he felt better, though he didn’t look it. He obviously needed medical attention. Charley was boss; there would be no argument. We would take Joe down after lunch, then come back for the tents and trophies.

Before long we were on the horses, riding out into brilliant white light and total silence. We tiny men and horses moved slowly past towering, snow-covered pinnacles. The air was still. Ice muted the sound of the river and snow the horses’ hoofbeats. For hours we rode through the wintertime spectacle, warmed by its beauty and our thick wool clothing. Still, I felt a tingling in my fingers and nose. And the moisture of our every breath froze in the thin air.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself. Buy Now

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself. Buy Now