The most important advance in 80-plus years in our understanding of bobwhite quail ecology—or, more to the point, bobwhite quail mortality—has been the discovery that a certain parasitic eyeworm, Oxyspirura petrowi, not only has the potential to devastate quail populations on a landscape scale, but to do so with breathtaking, even frightening, rapidity. While this parasite has been known to science for some time, it’s only been within the last seven years that researchers have taken a hard look at it.

And they’ve been blown away by what they’ve found.

For starters, the eyeworm turned out to be vastly more debilitating than was previously believed. It attaches to the back of the eye and to the nasal membranes, where it feeds ravenously on its host’s blood. (It’s analogous in this respect to a hookworm in dogs.) An infestation of eyeworms will impair vision and breathing, cause anemia, and in general weaken the affected bird to the point that it becomes irresistibly easy pickings for predators.

The real game-changer, though, was the discovery that once the eyeworm becomes established in a population of quail, it can spread with dizzying speed.

On one study area in the Rolling Plains ecoregion of West Texas (one of the few places on earth where bobwhite quail remain widely abundant), the infection rate went from negligible to 90 percent in a matter of weeks. Not months, not years, but weeks. Scientists call outbreaks like this “epizootic events”—pandemics, essentially.

The upshot is that there’s a growing consensus that parasites may be the “smoking gun”—the “X-factor” that quail biologists have been searching for over the past decades in an attempt to explain population declines that seem to occur spontaneously and can’t be explained by habitat or weather.

It was just such a crash in 2010, when what appeared to be a healthy quail population all but vanished between July and November, that in 2011 prompted the leadership of the Rolling Plains Quail Research Foundation to implement Operation Idiopathic Decline: a massive, first-of-its-kind effort aimed at determining if disease, parasites, toxins in the environment, or some combination thereof could be behind these inexplicable (i.e., idiopathic) mortality events.

Within a remarkably short period of time—three years, basically—the team assembled by the RPQRF and led by the Wildlife Toxicology Laboratory at Texas Tech University had zeroed in on the eyeworm as having the potential to be “a significant limiting factor” on bobwhite populations in the Rolling Plains.

A parasitic cecal (intestinal) worm, Aulonecephalus pennula, was also identified as a significant mortality factor. Even more widely distributed than the eyeworm (and especially prevalent among South Texas bobwhites), it inhibits the ability of affected birds to absorb nutrients, causing them to literally starve to death.

Since then, the team has gone on to develop an anthelmintic that’s proven to be highly effective at eliminating both the eyeworm and the cecal worm and to incorporate this compound into a medicated feed. Trademarked under the name QuailGuard, the feed is soon expected to win FDA approval and become commercially available. The challenge ahead will be to puzzle out the most effective, efficient way to deliver it to a wild population of birds.

“I’m confident that we will,” says Rick Snipes, the former president of the RPQRF’s board of directors and the driving force behind Operation Idiopathic Decline. “I tell people that right now we’re still in the ‘bag phone’ stage, but it won’t be long before we’re in the ‘iPhone’ stage.”

Adds Snipes, whose visionary leadership at the helm of RPQRF helped him become the 2018 recipient of the T. Boone Pickens Lifetime Sportsman Award from Park Cities Quail (joining the likes of Tom Brokaw, Delmar Smith, and George Strait): “We’re not going to eradicate these parasites. Our hope is that we can control them and prevent the kind of outbreak that can cause quail populations to crash even when the weather’s favorable, as we saw in 2010 and as we appear to be seeing to a somewhat lesser extent this year.”

Adds Snipes, whose visionary leadership at the helm of RPQRF helped him become the 2018 recipient of the T. Boone Pickens Lifetime Sportsman Award from Park Cities Quail (joining the likes of Tom Brokaw, Delmar Smith, and George Strait): “We’re not going to eradicate these parasites. Our hope is that we can control them and prevent the kind of outbreak that can cause quail populations to crash even when the weather’s favorable, as we saw in 2010 and as we appear to be seeing to a somewhat lesser extent this year.”

Needless to say, all this R&D hasn’t come cheap. The RPQRF has invested some $4 million in Operation Idiopathic Decline thus far, and while they’ve made tremendous strides, there’s still a long way to go to reach the finish line. Plus, that $4 million is on top of the nearly $3 million spent since 2007 (when the RPQRF came into existence) on other research projects, educational outreach, and operational expenses, including management of the 4,700-acre property near Roby, Texas, that serves as the Foundation’s headquarters and distinguishes it as the only quail conservation organization in the world with its own research ranch.

Since its inception, the RPQRF’s primary financial benefactor has been Park Cities Quail, the Dallas-based entity whose annual banquets have on several occasions raised more than $1 million in a single night. The Texas Quail Coalition, a group comprised of a number of member chapters throughout the Lone Star state, has been another important supporter, as has the Reversing the Decline of Quail Initiative of the Texas A&M Agricultural Extension Service.

But these groups can’t do it alone, and with more funding sorely needed not only to maintain the momentum the RPQRF has generated over its first decade but to propel it into its second and beyond, it recently rolled out the Campaign for Quail.

But these groups can’t do it alone, and with more funding sorely needed not only to maintain the momentum the RPQRF has generated over its first decade but to propel it into its second and beyond, it recently rolled out the Campaign for Quail.

Undoubtedly the most ambitious undertaking in the history of quail conservation, the Campaign for Quail seeks to raise $22.9 million over the next five years—money that will enable the RPQRF to continue the important work it’s started, the parasite research in particular; to expand its reach beyond the Rolling Plains to other areas of the country where bobwhite and/or scaled quail were historically abundant and where restoration appears feasible; and to launch new initiatives aimed at preserving the legacy and culture of quail hunting and recruit new participants to the sport.

The defining focus, of course, remains what it has always been: to increase populations of bobwhite and scaled quail in the wild and, thereby, “preserve the heritage of wild quail hunting for this and future generations.”

“We’re at an exciting place,” notes Justin Trail, the sportsman from Albany, Texas, who took over as the RPQRF’s president last November. “I like to say that we’re not at a stopping point, but at a going point. We’re on the cusp of making the medicated feed available to the public, and we’re teed up to figure out the best way to deliver it to the birds.”

“What we’ve accomplished so far has been mind-boggling—a testament to Rick Snipes’ leadership—but the next two to three years will be crucial.”

Adds Trail: “The eyeworm research has become our sort of sexy public persona, but there’s so much other important work we do, and intend to continue to do, in terms of educational outreach and utilizing our ranch as an outdoor classroom. We need to help create a new generation of quail hunters and quail ‘enthusiasts,’ too, and we’re committed to moving the needle in that respect. Our philosophy is, ‘If we build it, they will come,’ and that’s what makes the Campaign for Quail such an urgent priority.”

“We were fortunate,” reflects Rick Snipes, “to experience that ‘existential moment’ that every good organization comes to sooner or later in 2010, when we were still in our infancy. When the birds simply seemed to vanish that year, it became incumbent on us to find out why and to put that quest ahead of our own existence, even if it meant spending every dollar we had. And we did!

“So now the question is: Is this organization worth having around? Obviously, I believe the answer is yes. When we instituted Operation Idiopathic Decline in 2011—the project that eventually led us to the eyeworm and the cecal worm—it was the first time anyone had seriously looked beyond the parameters of weather and habitat in an effort to solve the mystery of declining quail populations. This has clearly established us as the forward thinkers of this business—the guys who are willing to ask the hard questions.

“I also firmly believe that the answers we find with respect to quail will prove to be transferable at some level to other Western gamebirds—lesser prairie chickens, for example—and that biologists will be able to build upon that knowledge to restore those species, as well.”

Dallas sportsman Joe Crafton, who as chairman of Park Cities Quail and a member of the RPQRF board of directors has a foot in both the demand and supply sides of this equation, offers a final thought.

“There’s no FEMA for quail,” Crafton observes. “It’s up to us as sportsmen to step up, give back to this bird that’s been so meaningful to us, and put the RPQRF on secure financial footing for the future. An organization that’s become the nation’s standard-bearer for quail research and the heritage of quail hunting shouldn’t have to survive banquet-to-banquet.”

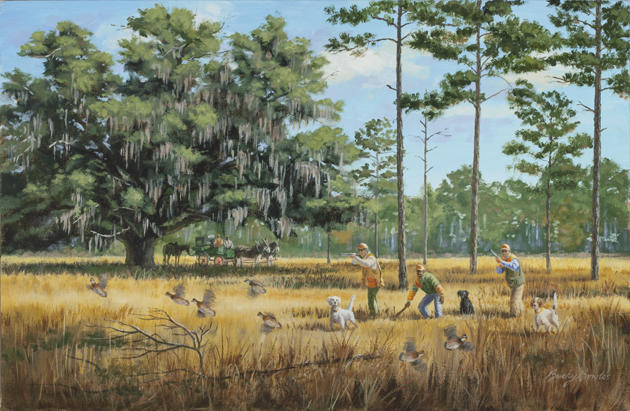

Bottomly Quail Hunt

Crafton notes, too, that the Campaign for Quail includes a variety of naming opportunities for major donors, from renaming the Foundation itself to endowing ongoing programs and permanent staff positions (similar to endowed professorships at a university).

To receive a prospectus or make a donation to the Campaign for Quail—I can think of no finer way to honor anyone who thrills to the sight of bird dogs drawn up tight on point and the roar of whirring wings—contact Phil Lamb, the RPQRF’s director of development, at (214) 498-1234 or plamb@quailresearch.org.

Will the sweet sound of whistling wings, the heart-stopping beauty of a sunset point, the timeless partnership of a man and a dog wise in the ways of wild birds ever return? Perhaps, but for now we can rejoice in the fact that we can, through the writings of some of the finest sporting scribes America has ever produced, experience those golden days vicariously. This 368-page book opens with compelling tales by the literary giants from quail hunting’s golden era, including Nash Buckingham, Robert Ruark, Havilah Babcock, Archibald Rutledge and Horatio Bigelow. Shop Now

Will the sweet sound of whistling wings, the heart-stopping beauty of a sunset point, the timeless partnership of a man and a dog wise in the ways of wild birds ever return? Perhaps, but for now we can rejoice in the fact that we can, through the writings of some of the finest sporting scribes America has ever produced, experience those golden days vicariously. This 368-page book opens with compelling tales by the literary giants from quail hunting’s golden era, including Nash Buckingham, Robert Ruark, Havilah Babcock, Archibald Rutledge and Horatio Bigelow. Shop Now