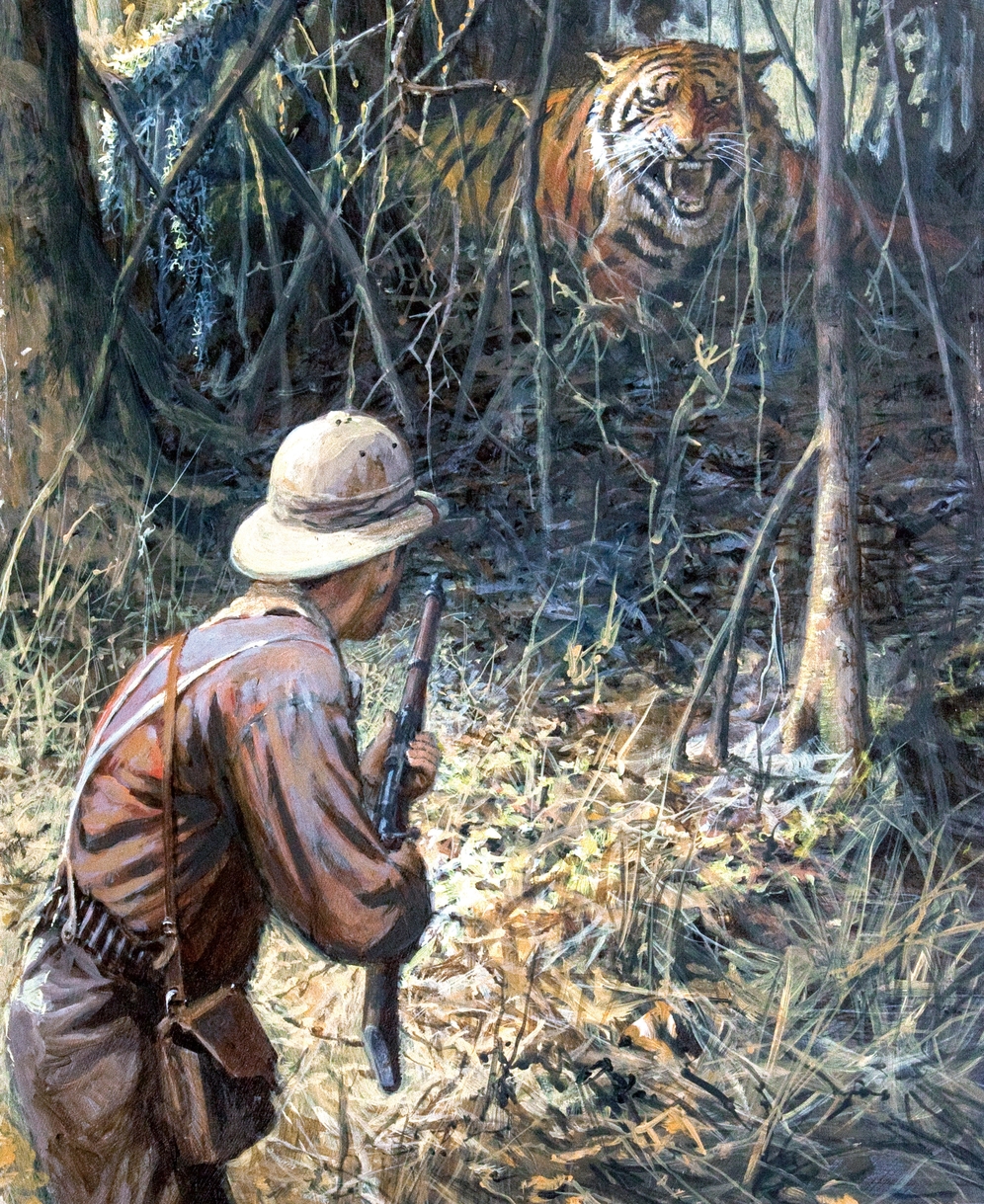

The long search for the man-eating tigress was coming to an end and the hunter was poised to bring a permanent halt to the killer’s reign of terror.

After a trek lasting three days, he was finally going to come face to face with his deadly quarry. He knew that the slightest disturbance in the bush could cause the tigress to flee.

That day and on previous days, Jim Corbett had a team of some 30 beaters working hard to flush and drive the tigress toward him. They were not having much luck and were about to call it a day and try again the following morning when Corbett’s attention was drawn to a distant field adjacent to a village.

Man Eater of Kumaon by John Seerey-Lester

He couldn’t believe his eyes. The elusive tigress was casually walking toward them about 400 yards away. Corbett looked for some cover and a good position from which to take his shot. Meanwhile, the big cat started down a ravine toward a narrow stream. Corbett quickly made his way to where he hoped to get a shot before or after she crossed the water, but there was insufficient cover.

As the tigress began to climb over the crest of the hill, Corbett knew he’d have to move fast if he was going to cut her off before she disappeared. Determined not to lose his chance, he had no other option but to race headlong through a tunnel of thorn bushes that tore at his skin and clothes.

With blood trickling down his face, the hunter eventually scrambled out the thorns and found a vantage point above the ravine where he expected to see the tigress feeding on the carcass of an old bullock he had put there the day before. As he crawled up to the rim, he was relieved to hear bones cracking below him, which meant the tigress had found the kill.

During the early half of the 20th century, Jim Corbett was one of the most famous hunters of man-eating tigers and leopards. Born in 1875 of Irish ancestry in the small Himalayan town of Nainital in the Kumaon area of northern British India (now the State of Uttarakhand), Edward James Corbett soon became dedicated to ridding Indian villages of the killer cats.

During his long hunting career, he never slayed a tiger or leopard unless it was killing humans. It’s estimated that the cats he killed were responsible for the deaths of some 1,200 men, women and children.

Around the mid 1920s, Corbett had been called to Muktesar, a small picturesque settlement in the shadow of the Himalayas. Apparently a troublesome tigress had taken up residence in the forest area near a Veterinary Research Institute specializing in fighting cattle diseases.

The tigress had quickly graduated from attacking livestock to killing humans. At least 24 people had been killed by the tigress and something had to be done about her. Like most man-eaters, the big cat had probably suffered an injury that caused a change in her diet from wild animals to humans, a much easier source of prey.

The tigress was terrorizing and endangering the lives of the villagers as well as workers at the institute. Because it was a Government-run facility that was doing important work, it became a priority to find someone who could resolve the situation.

Corbett was called in, though at first he was hesitant; he worried that he might be stepping on the toes of the sportsmen who lived around the institute and who had tried unsuccessfully to kill the tigress. But after hearing the horror stories of how people had been brutally slain, he signed on for the task.

Corbett always required physical evidence of an attack or to be taken to the site of the tragedy. Upon his arrival, he was shown where a local woman had been cutting grass for her cattle when the tigress pounced, striking her with a fatal blow and then crushing her skull. The woman’s death was instantaneous, but surprisingly, the cat chose to seek refuge elsewhere instead of feeding on the corpse.

Two days later, a man had found the woman’s body, still clutching a clump of grass in one hand and a sickle in the other. The man was also killed by the tigress, which had been lying in wait not far away. For some reason, the tigress fed on the man, but had decided to leave the woman untouched.

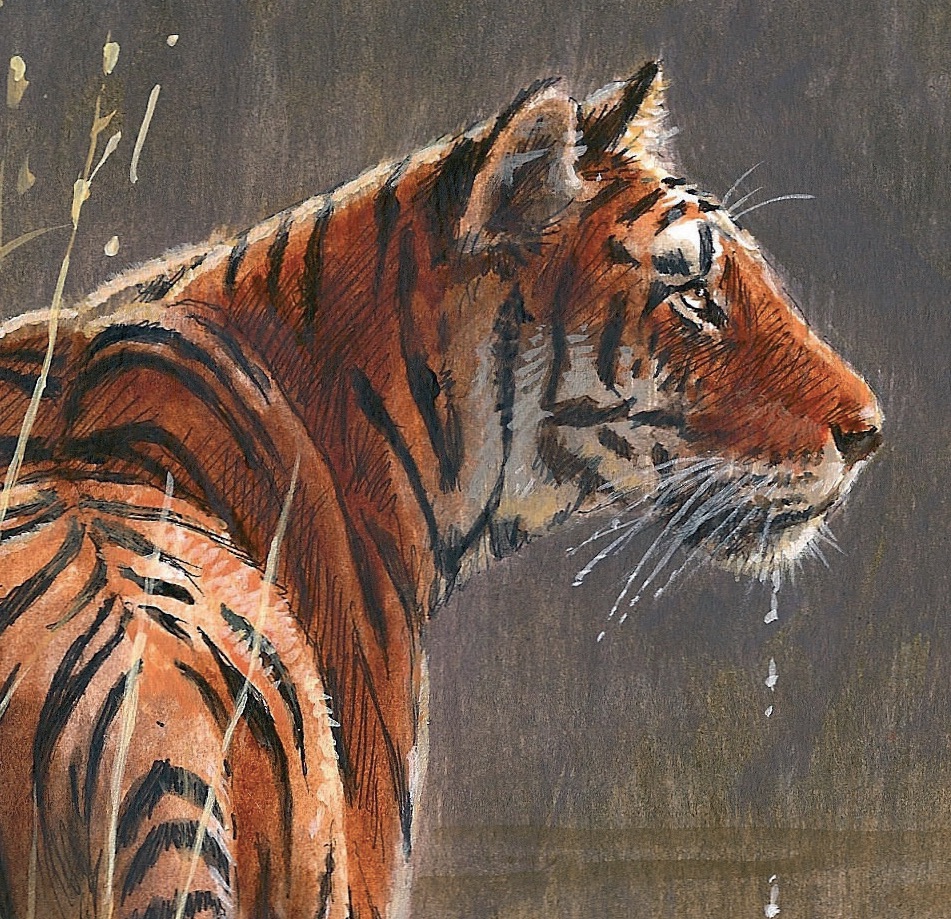

Detail from Distant Danger by John Seerey-Lester

A day later, she killed a third villager without any provocation, which elevated her to the top of the wanted list.

Now Corbett was within striking distance of bagging the big cat, unless something unexpected happened. From his vantage point above the tigress, he watched as she left the kill and began to move out on to open ground. Suddenly he was startled by a sound behind him; it was one of the beaters who had retrieved Corbett’s hat that he’d lost during his run through the thorn tunnel.

Corbett thanked the beater, then motioned for him to keep quiet. The tigress was close by, climbing up the opposite bank and walking along the top toward a hill where she would soon be obscured by a thicket of poplar saplings, each about six inches thick. Although he could only see a shadow of the cat moving through the trees, Corbett decided to take the shot.

The blast from his rifle echoed through the valley as the bullet hit a sapling near the cat’s head. The tigress reacted instantly, swinging around and charging down the hill toward Corbett, who realized he was trapped with his back to a sheer 50-foot drop to the stream below.

When the cat was only two yards away, Corbett leaned forward and fired his last bullet, which struck the tiger at the base of her neck. The impact of the 500-caliber bullet pushed the tigress off course, but her momentum carried her past Corbett and over the cliff to where she fell into the stream with a huge splash.

As the villagers and beaters cheered from the cliff-top, the dead cat was hauled up from the stream and laid on a bed of straw for all to see. An hour later, by the light of lanterns and in front of a growing crowd, which by then included several local sportsmen, Corbett skinned the tigress. He found that one of her forelegs had some 50 porcupine quills imbedded under the pad, which had become ingrown. This was obviously what had turned the cat into a man-eater.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers. Buy Now

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers. Buy Now