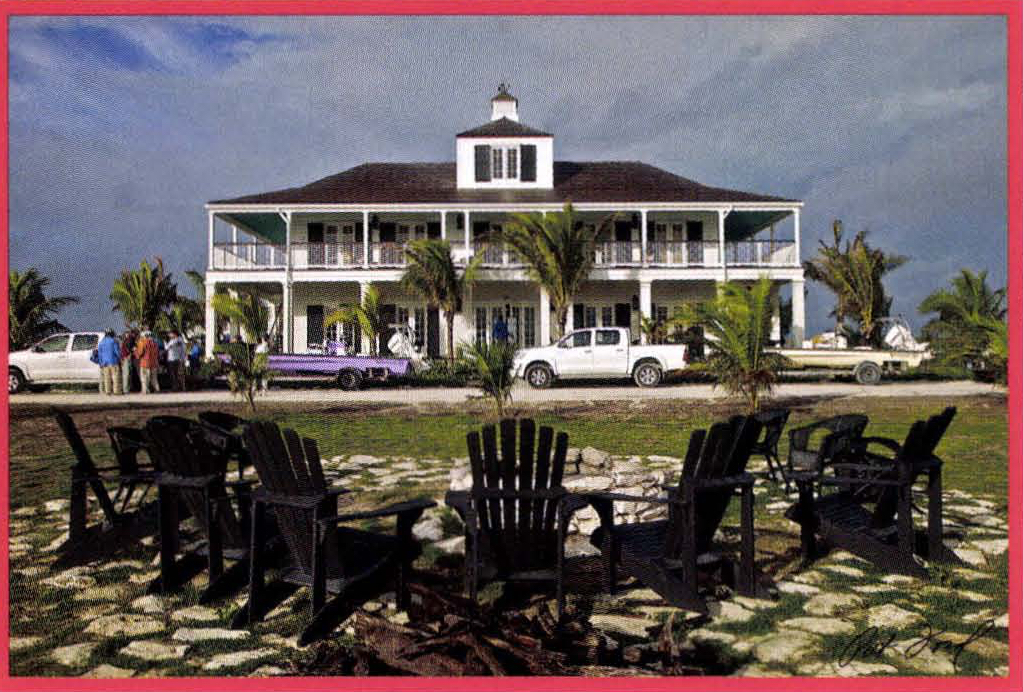

Blackfly Lodge at Schooner Bay anchors a Bahamas community created especially for fishing.

On a calm day, the slight slap of the water on the hull of a flats boat has one of two effects on me. If I’m tired, it can lull me into a trance, the kind that makes me want to find a sandy beach, roll up my shirt into a pillow and take a nap. On those days, I can easily lapse into a slumber so deep and hard that my friends call me Rip van Winkle, and I can account for the audible equivalent of two cords of split and stacked wood.

The other is a completely opposite effect – a heightened focus and intense concentration. I know in my bones where the fish will be and where they will go. I intuitively know when fish will move from the shadows into the open. I am always one step ahead of them and because there is magic in the air, I can jockey into position for a cast that hits the mark.

I felt both effects while standing on the bow of Blackfly Lodge’s East Cape skiff. I could easily have dozed off, but I hadn’t traded the cold, winter winds for the balmy warm breeze just to nap. There were palm trees all around, coral heads and white sand – and schools of bonefish to keep me awake.

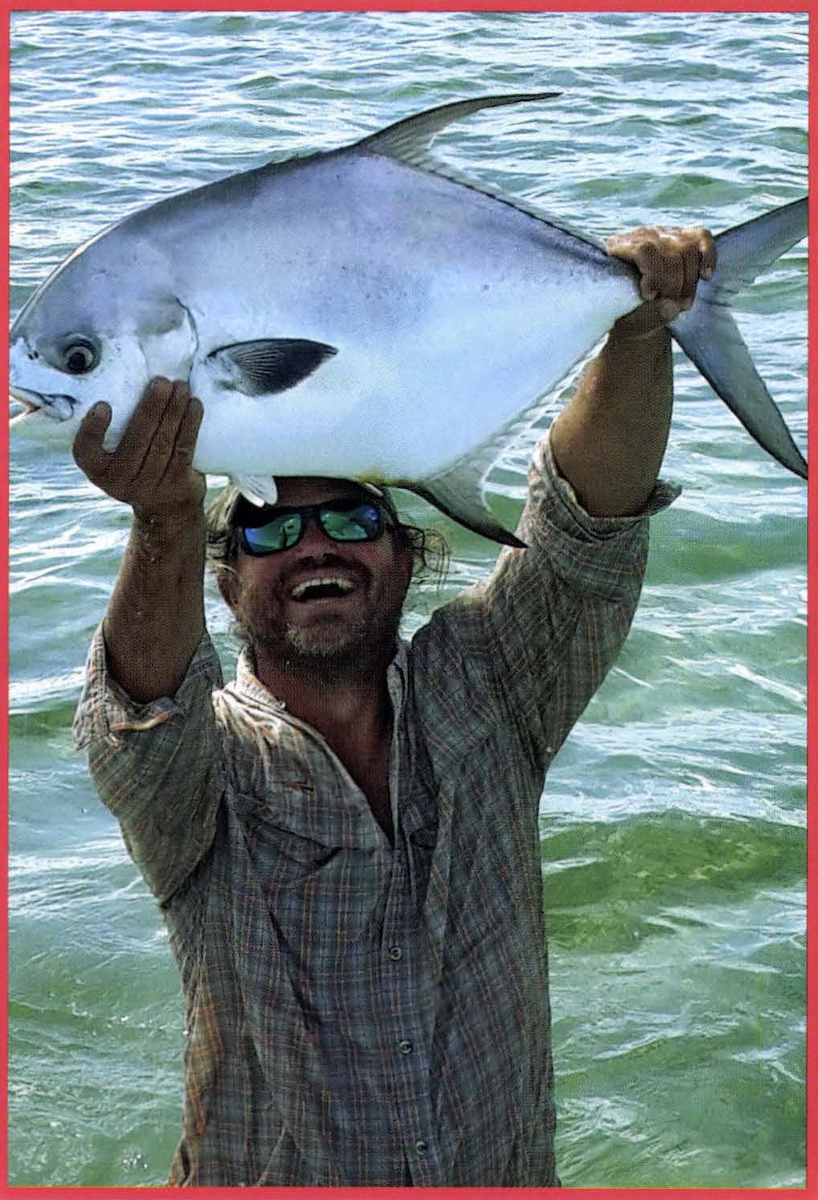

Cochran and a 12-pound bone fish.

I studied the tidal creek that drained out to a medium-sized fiat. It was rimmed by coral, which made it look like a small pond. About a hundred or so yards away was an entrance and about a hundred yards behind me an exit. The dropping tide was strong enough to wash away the sand and uncovered thousands of shrimp and crabs. Bonefish knew the drill and that meant my guide did, too. In short order the bones would move into this protected area from deeper water, tip their heads down and their tails up and feed for hours.

Our plan was to drop the hook, get out of the boat, and wade and stalk. We’d slowly work up to the creek, wading along the flat and seeing the fish the whole time. The water was calf-deep and dropping, and the bottom was firm. Th sun and wind were at our backs, and the sparkling turquoise water carried a slight greenish hue. I took my time for there was no need to rush. Instead, I looked for shadows of moving fish and the silver slivers of tails.

And they came, slow to start, the single fish at first. They were hungry, you see, and that meant that they were easier to fool with a Gotcha, a Peel and Eat or a Queen of Abaco.

A silvery fish moved light up into the current, tipped up and opened its big lips to suck in the fly. When it felt the iron, it turned to exit but found only the rim of coral in its way.

Running bonefish and singing drags are always fantastic, but in this particular spot the fish had only one way to run: across the flat. The fish blasted across the flat, leaving a wake and a cloud of sand as they looked for an escape route, but as we were far from the exit, their only option was to run and run some more.

Vaughn Cochran, co-owner of Blackfly Lodge at Schooner Bay, casts to a pod of bonefish on a sunny flat alongside Abaco Island.

Solo fish were soon replaced by doubles and triples, and after a while bigger schools arrived. I prefer to work small numbers of fish; it’s just plain fun. One or two fish give me the opportunity to really focus on their movements. If they don’t eat I can vary my approach. If they’re calm and relaxed, I might have time to change fly patterns. I feel a tremendous satisfaction when I get one to eat.

That said, there is something exciting about dropping a fly ahead of the leading edge of a big body of fish. The natural competition cranks them up and makes them aggressive, and so it’s anyone’s guess which fish will grab the fly. The smaller bones are more nimble but the bigger fish have greater bursts of speed. Regardless of size, when a bonefish is hooked the entire school erupts like a depth charge blowing up near the surface. These memories are the ones that will carry me through the remainder of the winter.

Guide Robert Albury and a pair of snappers.

Blackfly Lodge at Schooner Bay is dramatically different from any other fishing venue in the Bahamas. Its location on Abaco’s East Coast is interesting; it’s south of Cherokee Sound and north of the famous Hole in the Wall.

What makes the lodge unique is that visionary Orjan Lindroth’s concept was certainly more far-reaching than to just find a location in close proximity to great flats fishing; his was to create an entire town.

A Swedish-born and Bahamas-raised entrepreneur, Lindroth was committed to creating a village that was in keeping with the relaxed, low-key plantation style that typifies traditional island life.

“Our new urbanist style is a representation of a community where work and life are combined,” he said. “The homes are small and efficient; there is an economic band of goods and services that surrounds the harbor, and even our hundred acres uses a vertigro system where lettuce hangs from lines.

“For heating and cooling we use a geothermal plant that draws water from wells 600 feet deep. The water from that depth is naturally cold and adds a 40 percent greater efficiency in cooling. Cold water instead of air conditioning maintains a perfect temperature, and it’s environmentally sound. Since everything is so close, we’re a low traffic area. Schooner Bay is wonderful in every way.”

To Lindroth’s way of thinking, a fishing lodge was the perfect anchor location to attract a wide-variety of likeminded people to Schooner Bay. And as fate would have it, a company that specialized in fly fishing destinations already existed on the island, and had grown to the point where it needed to expand.

The foundation of many good things in life comes from art, and Blackfly Lodge at Schooner Bay is one of them. Several years ago, guide Clint Kemp called renowned nautical artist Vaughn Cochran to discuss a commissioned painting. A number of the long-time Bahamian guides were aging, and Kemp thought it would be nice to commemorate them and their dedication to the sport through a series of commissioned paintings. He asked Cochran if he would do a portrait of Crazy Charlie Smith. Many anglers know Smith as the creator of the Crazy Charlie shrimp pattern that led to universal acceptance not just of the fly but of the style used by other modem tiers to imitate shrimp. Cochran loved the sound of the project, quickly agreed and began painting.

The lodge and two of its East Cape skiffs.

When he was done with the portrait, Cochran flew to the island and the pair spent a day fishing with legendary Abaco guide Paul Pinder. On their outing Cochran said something prophetic: “Abaco reminds me of the Florida Keys twenty years ago.”

“Later that day we went to Pete and Gay’s in Sandy Point where we had a few cocktails and cigars and hashed out the concept of a fishing lodge,” said Kemp. “As most know, Vaughn has been around the fly fishing entertainment business since the 1970s. He has worked with countless lodges over the past forty years throughout the tropics and Mexico, developing some, and owning and then selling others. At this point in his life he owns Blackfly Outfitters in Jacksonville, a restaurant, and an art gallery. Creating a team with this high-skilled entrepreneur was a no-brainer.

Blackfly Lodge co-owner Clint Kemp gleefully

hoists a big permit.

“We began by literally testing the waters with a rental property to see if there was in fact a market. We bought some boats and created the traditional Bahamian plantation house concept and quickly proved that it was viable. One of my clients was a Canadian named Dave Byler. Dave was a long-standing, well-traveled sportsman who focused on fly fishing in his home waters on the world-renowned Bow River.

“Dave is a passionate and excellent angler, and when he retired from Sun Corporation he asked if we needed an equity partner. In the process, Vaughn and Dave had become fast friends, and the three agreed to launch Black Fly Lodge at Schooner Bay. We were meant to be.”

Blackfly Lodge has been a reality for a few years now. There are eight guest suites with private bathrooms and stunning views. Each room is named after a fishing personality, including Lefty Kreh, Flip Pallot, Joan Wulff and the like. You’ll know which room you’re in by the original Vaughn Cochran painting hanging on the wall. The open kitchen format enables guests to watch Chef Devon Roker curried conch chowder, steamed hog snapper in parchment paper and guava cobbler with a rum butter sauce, and also to taste a goat cheese, pesto and spiny lobster pizza appetizers.

Guest anglers Bob Sylverstein with a huge bonefish.

On a cool everning, guests relax in the living room, and when the weather is perfect (which is much of the time), they’ll relax on the veranda and watch boats enter the harbor. For those who prefer privacy there is a home rental program, too.

Fishing in the area is perfectly ideal, and none of it requires extensive runs or drive times (the boat ramp to fish the west side is a mile away). There are the protected flats of Cross Harbor and Sandy Point to the south, the famous Marls of Abaco to the north, and miles of flats, channels and mangroves to suit every angler’s fancy.

On a clear day anglers can run to Moore’s Island, renowned for its phenomenal fishing for trophy bones. The crew operates four custom East Cape Vantage skiffs, each brightly colored with customized leaning posts with cushioned seats. The skiffs are phenomenally dry and stable and comfortable for long or short hops. They also run two Beavertails and one Hewes Redfisher.

The lighting in the afternoon was exquisite. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky and the soft wind didn’t create so much as a ripple. I could see more clearly than ever. Sometimes I saw a flash of silver when the sun hit a fish’s side while other times I saw the fish tilt their heads down to suck in a shrimp. When the fish turned to swim away I lost sight of them and knew where to cast when their shadows appeared on the bottom.

David Hughes with his 60-pound tarpon.

One fish, a good one at that, worked a seam about 30 feet from the bow and turned to swim away. He wasn’t spooked, he just wanted to go in a different direction. I did a roll-cast pick-up, false-caste to the side, and worked out about 50 feet of line. I looked down to be sure I wasn’t standing on the running line, picked a spot out in front of the slowly cruising fish and shot some line. The fly dropped softly about ten feet in front of him and slowly sank to the bottom.

The fish stopped and didn’t move.

I began my retrieve. Strip, strip, strip . . . he just sat there. Strip, strip … and he lurched forward.

Damn, I thought, I spooked him.

And then, just as a vacuum cleaner sucks up a ball of setter fur from the corner of a room, my line went tight. I gave two strip-strikes and watched the line jump from the bow of the boat into the air. In an instant my reel was singing and my line was slicing through the water. The sound of a hard-running bonefish is perfectly sweet. And this, too, is exactly why I came to Blackfly Lodge.

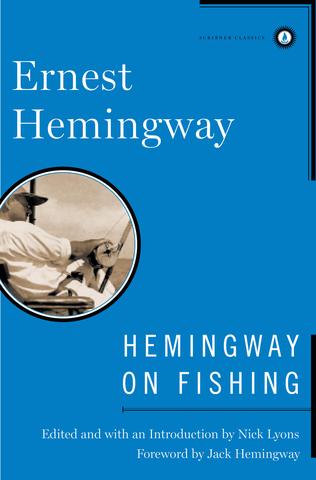

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature.

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature.

From childhood on, Ernest Hemingway was a passionate fisherman. He fished the lakes and creeks near the family’s summer home at Walloon Lake, Michigan, and his first stories and pieces of journalism were often about his favorite sport. Here, collected for the first time in one volume, are all of his great writings about the many kinds of fishing he did—from angling for trout in the rivers of northern Michigan to fishing for marlin in the Gulf Stream.

In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway speaks of sitting in a café in Paris and writing about what he knew best—and when it came time to stop, he “did not want to leave the river.” The story was the unforgettable classic “Big Two-Hearted River,” and from its first words we do not want to leave the river either. He also wrote articles for The Toronto Star on fishing in Canada and Europe and, later, articles for Esquire about his growing passion for big-game fishing. Two of his last books, The Old Man and the Sea and Islands in the Stream, celebrate his vast knowledge of the ocean and his affection for its great denizens.

Anglers and lovers of great writing alike will welcome this important collection. Buy Now