Shooting swan by night may seem hardly the correct thing in the estimation of many, but we fowlers of the wild and “feathery” West occasionally obtain under cover of the night what we cannot always acquire by the light of day. And so, at a friend’s suggestion, it came about that he and I decided to put in a night after swans before they left us, perhaps forever.

It was in the early 1880s and in Oregon that this deed of darkness was perpetrated. It had not been a good year for ducks; the home-bred wood ducks and mallards had been pretty well shot out before the winter rains set in, by which waterfowl of the great Northwest are so innumerably augmented. And, because these rains were very late in coming that year, our shooting had been considerably below average, hence our nocturnal visit to the sanctuary of the swans.

Six or seven miles from Portland, on the Oregon side of the mighty Columbia River, runs an immense piece of bottomland known locally as the Columbia slough. Dotted here and there along this bottom are numerous ponds and lakes, every one of which, in turn and season, is well tenanted with wildfowl.

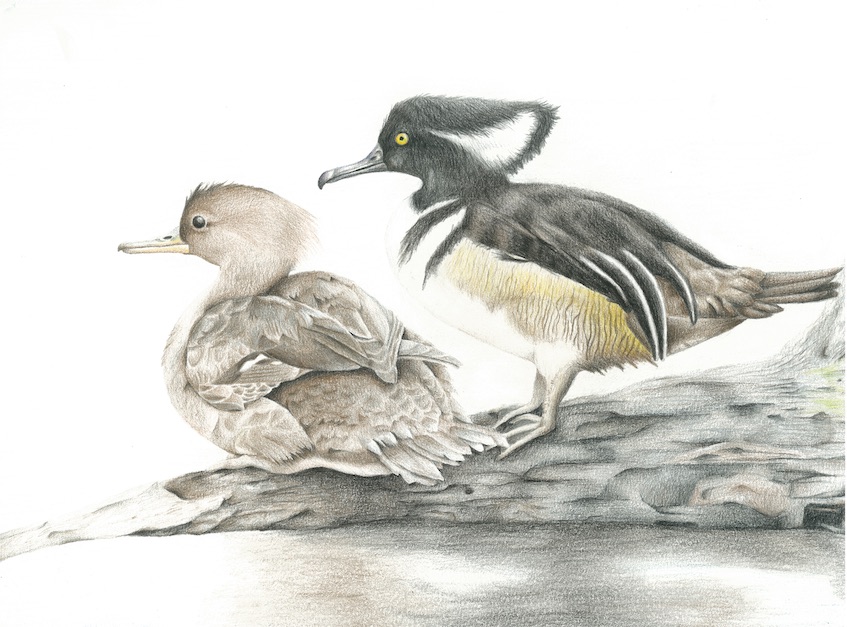

Growing in the greatest profusion on these waters is the succulent wapitou, a bulbous root of acorn shape that to the wildfowl of Oregon is what the wild celery is to waterfowl of the Chesapeake. Only swans and deep-water fowl such as the canvasback are able to dig the bulb from its tenacious muddy bed, usually two to four feet below the surface. Widgeon and other wildfowl ride gracefully at anchor close by the spot where some hungry canvasback has recently disappeared. When it comes to the surface with its hard-earned spoil, they frequently pounce upon the luckless bird, resembling a thieving horde of shallow-water pirates.

The American swan, Cygnus Americanus, also contributes materially to the levying fowl around him. His head and neck will disappear, followed soon after by a rocking motion of the body as his powerful feet excavates the precious root from the mud. Lots of little tidbits thus freed rise to the surface to be immediately seized by the numerous tribe that follows in the swan’s wake.

One evening in December (the night before Christmas), a farmer friend of mine who owns a milk ranch on the Columbia slough drove to my home in East Portland and invited me to get my gun and about a dozen shells and go with him to Old Dave’s place on the slough for “a whack at the swans.”

It had not been a good year for ducks; the home-bred wood ducks and mallards had been pretty well shot out before the winter rains set in

I had been duck shooting that day already, but I never refuse a good offer to shoot wildfowl, so long as I can keep an eye open or have a leg to stand on. So getting back again into my long rubber boots and donning a couple of flannel shirts, my shooting jacket and overcoat, and taking a 12 gauge and 25 shells loaded with No. 3 shot, I jumped into the car and we were soon on our way to the riverbottom.

Old Dave was then a wealthy man, whose road to riches began when he purchased his first piece of real estate from money raised by selling wildfowl that fell to his gun at a time when land was cheap and ducks were plentiful.

Half-an-hour’s drive by horse-cart brought us to a long muddy lane leading to Dave’s lake. Presently, the pony clattered over the log bridge spanning the last slough and, after pulling up in a fence corner, we threw a blanket over his steaming loin and left him to a heap of hay and his ruminations.

My friend (whom we will designate as P.) had a 16-bore and No. 1 shot, not a gauge most fowlers would advocate for use on swans, but one that did good service nevertheless.

We first walked down to the lake’s end and inspected the boat, which seemed a bit too weather-beaten and frail for two men to put out in. I expressed my opinion to P., who laughed at the idea, assuring me that even if we did swamp, the deepest place in the lake was less than three feet.

To that, I countered: “Deep enough, with twelve inches of mud added, to get thoroughly wet in.”

After caulking some of the seams with contributions from our handkerchiefs, we put off and rowed quietly through the chain of necks and loops into the lake proper.

Presently, P. ceased rowing and, listening an instant, remarked “D’ye hear ’em?”

Yes, I heard them. From way over in the bend of the lake toward the timber, came clear and distinct, the resonant call of swans.

“Now,” said P., “tell you what we’ll do. We’ll pull ashore here, and I’ll run and take a stand just this side of the cottonwoods, while you scare ’em out. And, see here,” he added emphatically, just before stepping from the boat, “if you hear me shoot, have everything ready to pull out the moment I get back ’cause the hired man at Sunderland’s will be down with a gun, for sure, when he hears the shooting. Don’t scare ’em out till I whistle.’’ With that, he disappeared in the night.

It was now about ten o’clock on a peculiar night. No moon was visible, though she must have been riding high somewhere behind the fleecy, quick-traveling clouds. Away across the lake could be heard the calling, flapping and splashing of the fowl we sought. A little breeze was stirring—the only element of the night that caused P. to steer for the cottonwoods, his instinct, born of that breeze, telling him almost to a certainty how the birds would fly once disturbed. The only other sound was the barking of some dogs from where a solitary light twinkled on a distant hill.

Ten minutes perhaps had passed when a long, low whistle came from the vicinity of the dark line of cottonwoods.

Now, how to raise the birds? I clapped and then called as loudly as I dared. All the sounds on the waters immediately ceased, but not a bird moved. There was but one other way I knew of to lift them from the shore, a very subtle and effective method, though not advisable as a rule—simply to strike a light. The lucifer burned within the hollow of my hands and, then at its instant of extreme lightness, I exposed it.

A moment’s quiet supervened that in its intensity was almost oppressive. Then came a clanking roar from out on the lake where the swans were a-wing. A few moments later and the heavy beat of their many wings fell faintly on my ears as they filed complainingly out into the night. A few moments more and seemingly out from under the dark-blue line of the cottonwoods leaped two flashes of flame in quick succession, followed an instant later by two startling reports, then thump, thump as two heavy bodies struck the yielding earth, telling that the little 16 bore had not spoken in vain.

I held the boat’s stern right ashore, and presently I could detect the rapid swish-wish of P.’s corduroys as he hurried over the sward, then his heavy breathing until at last his tall figure appeared at the lakeside. Swinging two heavy swans off his shoulder and into the boat, he gasped, “Pull out,” and jumped in.

Not knowing—and he being too winded to explain—whether he was pursued or not, I bent to the oars and pulled as vigorously as I considered the frail old craft would stand and was soon beyond gunshot. I expected at any moment to see some outraged individual open fire on us from the bank, but we were not molested.

In minutes we arrived at a small patch of reeds near the middle of the lake where we decided to tie up for the night. Pressing an oar into the mud, we made fast, and then placed the two swans in the water as decoys. We let them float whither they would, having nothing to set them up or secure them with.

An hour or more must have elapsed when we heard the beautiful calls of swans approaching from off in the night. P. lifted up his voice, and began answering their calls, which brought them nearer and nearer.

“If they come over,” whispered P., “you take the leaders and I’ll look after the rest.”

At judicious intervals P. would call, and I could not help but admire his clear, flute-like voice as it went echoing through the night. Presently, P. seized an oar and, with a whispered “Look out,” commenced to rock the boat violently, calling vigorously the while. Passing my thumb between the hammers and strikers to be reassured of their position, I prepared myself.

As P. ceased his call and commotion, there came clear and distinct from the heavens above us the purring whistle of the deluded fowl.

“Let ’em circle, let ’em circle,” whispered P. “They’ll come right down to the decoys if we let ’em.”

We could now hear the beat of their wings and, as they passed a lighter patch in the clouds overhead, I counted five of the noble birds.

Another well-timed call or two from P. and their line was broken as three swans, with wings steadily set, slanted down to the decoys, now some distance away from the boat. Two birds seemed hardly satisfied yet and took another turn around to my left. Then, feeling that the supreme moment had arrived, I pulled on the first and, as quickly as possible swung on the second which, with its wing snapped close to the body, whirled round and round like a windmill and struck the water with terrific force only a dozen yards from the boat.

Hastily reloading, I stopped my first bird as it flapped noisily along the surface, and P. winged a third from way out over the decoys.

In our haste to recover the game, the oar in the mud was snapped at the blade but, with the remaining one as a paddle and a couple of timely shots, P.’s cripple was secured and the other two gathered.

The two decoys had seemingly stranded, so we left them where they were. Only their bodies were visible, their heads and necks being under water, but at night, they were just as attractive as any other mute decoy would be, however shapely and good looking.

Deciding that no swans would come in again for a while, we lighted our pipes and made ourselves comfortable. The renewed barking of dogs away on the hill, and the occasional hurried wingbeats of some smaller fowl hurrying by were the only sounds that broke the stillness. After the warmth and excitement had abated somewhat, it seemed to get awfully cold. We buttoned our coats around us, but soon we were so cold that our pipes shook between our teeth.

One of the three swans was lying in the boat at my feet and a touch of warmth therefrom seemed to penetrate my boot. Leaning forward, I pulled the heavy fowl toward me and observed that both its wings were broken. Grasping the bird by the neck, I slung its body over my back where it seemed to lie quite admirably. Then taking a wing in each hand, I drew them under my arms and crossed them over my breast. Then giving the beautiful, boa-like neck a twist around my own, I laid my gun across my knees, folded my arms over the wings and complacently awaited the result of my experiment. Soon, a subtle warmth pervaded my whole body, and I was deliciously comfortable.

P. requested me to “take off that ghostlike apparition.” I suggested that he try the idea himself and, then, as far as appearances went, we should at least be equal. I was perfectly satisfied with mine. He tried it and, though “his wings” were a trifle intractable, being unbroken, he finally fixed them, and ten minutes after that he was snoring soundly.

It must now have been early morning—Christmas morning. The fleecy clouds of earlier night had become heavier and darker, and the moon at her highest altitude was barely distinguishable, shedding little or no light on the darkening waters that flip-flapped restlessly against the sides of the gently rocking boat. The warmth of my downy quilt, supplemented by the slow-dying heat of the swan’s body, induced sleepiness and, in a moment of unconsciousness, I fell asleep. How long, I know not, but my dreams were angelic.

Sleep had transported me into other realms, where the air seemed filled with soft musical sounds and seraphic forms floated lightly about me. Suddenly, my garb of snowy whiteness fell from me and I seemed to be rushing back to the “cold” earth with terrible velocity, fetching up in the boat (at that agonizing instant when annihilation seemed certain) with a start and shiver that waked me most effectually.

Snow was falling in large, downy flakes, and around and above us the air was alive with forms as nearly angelic in their beauty, whiteness and purity as deign to visit us here below.

Soon, from away to my right, came a clear, bugle-like call, and I knew that a magnificent bird was afloat somewhere in the air above me.

As we stood there waist-deep in water, clutching our battered craft, I explained as well as my chattering teeth would permit the cause of the catastrophe, and requested P. to hold the boat while I fished up the guns.

Almost like an echo to the call came another from the far left, and yet more distant bugles sounded softly over the lake. Fate had played us one of her kindest pranks, and more by good luck than anything else, we had situated ourselves in the best spot for sport under the existing conditions.

We were evidently upon their feeding grounds, and I was beginning to conjure up in imagination the pile of game we might have down and around us when morning dawned, if we only played our cards right.

Reaching forward, I endeavored to waken my sleeping companion with as little noise as possible when a swan suddenly appeared off to my left. I could hear the beat of its wings and dimly discern its form as it headed straight for the boat.

As I raised the gun to shoot, I became conscious of another bird approaching rapidly from behind, but sticking to the first, which I felt sure was the noble trumpeter, I pulled. Then, without waiting an instant to see the result of my shot, I swung around on the other, now presenting a beautiful side shot.

As I touched the trigger, a body went rushing past my head and behind me with a screech that was positively maniacal, and so close as to actually brush me with its wing.

A sharp collision, a tilt of the boat, and men, guns, swans and all were pitched unceremoniously into the chilly water. I knew how it all happened, for I saw enough of it to know. Excruciatingly uncomfortable as the cold ducking was, I could not help laughing at P.’s gasping and rude awakening from what perhaps but an instant before had been the sweetest of sleep and pleasantest of dreams.

Whether he thought we had been struck by a typhoon or a whirlwind, I could never satisfactorily learn; in fact, he told me afterward, confidentially, that he imagined he was “home and that the house was on fire.”

As we stood there waist-deep in water, clutching our battered craft, I explained as well as my chattering teeth would permit the cause of the catastrophe, and requested P. to hold the boat while I fished up the guns. But owing to the deepness and tenacity of the mud, I could not do this alone, so we two sorry-looking specimens tilted the boat until her keel was formed by the angle of one side and the bottom, then baling the remains of her out as well as we could with my cap (for P.’s had disappeared), I manipulated her from the stern, while P. stood clinging affectionately to an oar he had thrust in the mud.

Steering cautiously about the scene of the wreck, I soon felt a gun with my foot and, reaching down until my nose was almost under water, I recovered and placed it in the boat. It was my own, but P.’s was stepped on a minute later and recovered.

Then, I cruised around and picked up our dead swans along with the forcibly ejected side of the skiff. Upon the latter I laid out the birds and, there in the middle, looming up larger than any of the rest, and with a gaping wound extending across the breast from wing to wing, lay my beautiful trumpeter, the cause of our cruel collapse.

With both wings broken close to its body, it had fallen from high in the air, its heavy body striking with resistless force the inside upper edge of the boat’s side, dashing it from its fastenings. As the swan and timber went by the board on the port side, we were as unceremoniously tumbled out on the other.

Each now taking hold of our battered boat, we waded ashore where, having no further use for our craft, we cast her adrift. Then we shouldered our guns and game and started for the pony and cart.

Oh, how cold it was during those few minutes it took to reach the farmhouse. When we reached P.’s home, the early milkman was in the act of raising a cup of hot coffee to his lips, but it never reached there for, whether through astonishment or not, he replaced it on the table, while he contemplated our appearance with open-mouthed surprise. Meanwhile, I thoughtfully seized his cup and shared its hot, fragrant contents with my unfortunate comrade.

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the January, 1892 issue of Outing magazine.

The North Atlantic, the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the waves and the wind and the ducks – there’s no doubt that big water holds a lure for waterfowlers unlike any other.

The North Atlantic, the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the waves and the wind and the ducks – there’s no doubt that big water holds a lure for waterfowlers unlike any other.

But when it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you.

However, each of these places requires a separate technique, alternate decoys spreads and calling concepts, and different gear to use. He tells you how to approach each type of hunting for the weather and conditions. He knows when and when not to call. He describes the skills a good waterfowl dog needs to know for each place, things he’s taught his succession of Labrador retrievers over the years.

His knowledge of duck and goose hunting has been earned through both experience and education. A native of Michigan, he holds a BS in Wildlife Management from LSSU in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula which, he jokes, “was a good way to go to class in the morning and duck hunt in the afternoon.” His love for waterfowl has come through in the 20-plus years panting wildlife in his “other” job, with four state duck stamp titles and two state Ducks Unlimited Sponsor Print titles to his credit, as well as placing high in the national event.

But what sets him apart is his skill, his knowledge, and his techniques accumulated over nearly four decades, a dozen states, and a half-dozen Canadian provinces.

In a spot where more is often viewed as better, Smith weaves throughout personal hunting stories the important roles ethics play for the modern-day ‘fowler, how a full bag limit isn’t the end goal, but rather icing on the cake.

In all, this is one of the finest treatises on waterfowling to come out in years—because small water means big sport. Buy Now