When Ross Parker described Mana to Van Schalkwyk as ‘God’s Wild Chapel,’ he admits he was a bit skeptical.

Jaco Van Schalkwyk tells the story of a lion — a big male behaving territorially and angling in his direction. The cat has the subtle bloodstain of a fresh kill on his muzzle. Packing an irascible temperament, bothered that his family meal has been rudely interrupted, he’s trying to decide whether we are friend or foe.

Inside the panorama where the iconic animal survives in Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools National Park, artist and lion can feel the 21st century rapidly pinching in. Van Schalkwyk, who turned his recent encounter with the king of all beasts into a wonderfully engaging statement, wants his art to help cure the greatest threat facing Africa, which is how the rest of the world regards what’s happening there as “out of sight, out of mind.”

“When Ross Parker described Mana to me as ‘God’s Wild Chapel,’ I admit I was skeptical,” says the talented young wildlife painter from Johannesburg.

“I couldn’t imagine what could possibly be seen there that I hadn’t encountered elsewhere in my own country,” he adds. “Growing up in South Africa, I kind of smugly thought I knew all about the best wildlife and nature reserves, but what a surprise. The Zambezi Valley, where Mana’s located, is one of the most beautiful places on Earth. It is something quite spectacular and heart-palpitating to walk in a place where there are still free-ranging lions.”

Sebata by Jaco Van Schalkwyk

Van Schalkwyk is a rising star among a new generation of contemporary African artists. His classical approaches to painting wildlife are attracting attention among North American collectors. What’s interesting, however, is that his oil paintings of wild animals stand in marked contrast to a body of work for which Van Schalkwyk is better known in his native land.

For him, there is no conflict or contradiction between delving into idyllic nature scenes on one hand and, on the other, exploring allegorical, sometimes surreal depictions of subject matter involving race relations, religion, equality, freedom, and the environment.

Regarding the latter, heading into the bush has opened his eyes and mind, he says.

Although he does not carry a rifle, Van Schalkwyk could be considered kindred to the romantic artists of the 19th century and sportsmen such as Theodore Roosevelt who banded together in desperate times to save bison, elk, and other game animals in the American West.

“He is painting at a time in history where his artwork is important,” says Parker, a Rhodesian-born art dealer with galleries in Jupiter and Naples, Florida. “That’s why I picked him to be a pillar in a multi-year exhibition to raise awareness. For only being in his thirties, Jaco is amazingly versatile and his feel for his wild subjects is uncanny. It’s as if he has spent his whole life in the bush.”

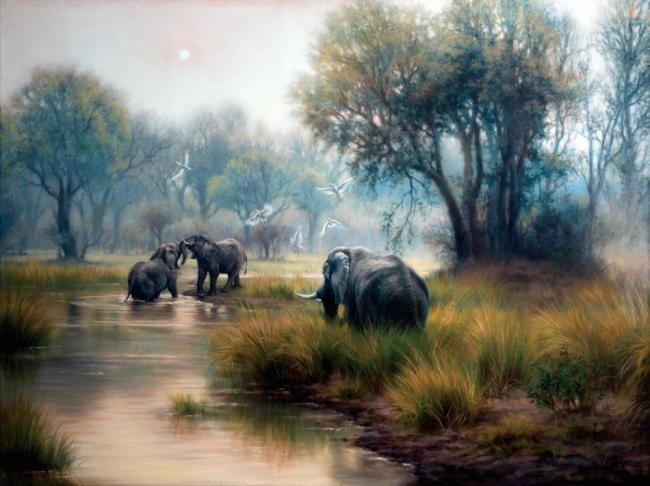

Reflections by Jaco Van Schalkwyk

Called “The Great Zambezi,” Parker has enlisted three artists—Van Schalkwyk, Zimbabwe and South Africa painter David Langmead, and Ndebele sculptor and carver Mopho Gonde—to produce works reflecting three key stretches of the Zambezi River watershed, a biologically rich corridor that many see as a bellwether for African wildlife.

“I brought these three together because they possess some of the greatest genius I’ve encountered in my thirty years of representing African artists,” Parker says.

The ambitious project, which will involve unveilings of new artwork at a handful of exhibitions between 2015 and 2017, visits Mana Pools in the first phase, North Luangwa National Park across the Zambezi in Zambia in the second, and, in the third, the river’s headwaters in the Okavango Delta of Botswana.

Blaze of Glory by David Langmead

As every well-traveled reader of this magazine knows, numerous iconic African species are in trouble—elephants and rhinos being ravaged by organized crime, predators (including all members of the cat family) being eliminated by poachers, and creatures of every hoof and feather being harvested to feed local people.

While writing this article, new stories about the plague of ivory and rhino-horn poachers, timber thieves in Zambia, and plans to open up Mana to possible oil and gas drilling appeared in only a week’s time.

Van Schalkwyk, Langmead, and Gonde want to prick the consciousness of viewers, not with doom and gloom but scenes of overwhelming beauty. Like the great American painter Thomas Moran, whose portrayals of the northern Rockies helped convince members of Congress to set aside Yellowstone as the world’s first national park, the remarkable trio hopes their art can have a similar impact.

Hunter/Hunted: The Kill by Jaco Van Schalkwyk

“The main focus with my paintings are landscapes where the animals become part of a bigger scene so that we understand the context for where they live,” Van Schalkwyk said while preparing new works that will be formally unveiled in Parker’s gallery displays at Dallas Safari Club and SCI in Las Vegas. “Although I have visited some of the great South African parks from a young age, I considered myself a city boy so this is as much a revelation for me as it will be for the viewers who see what we produce.”

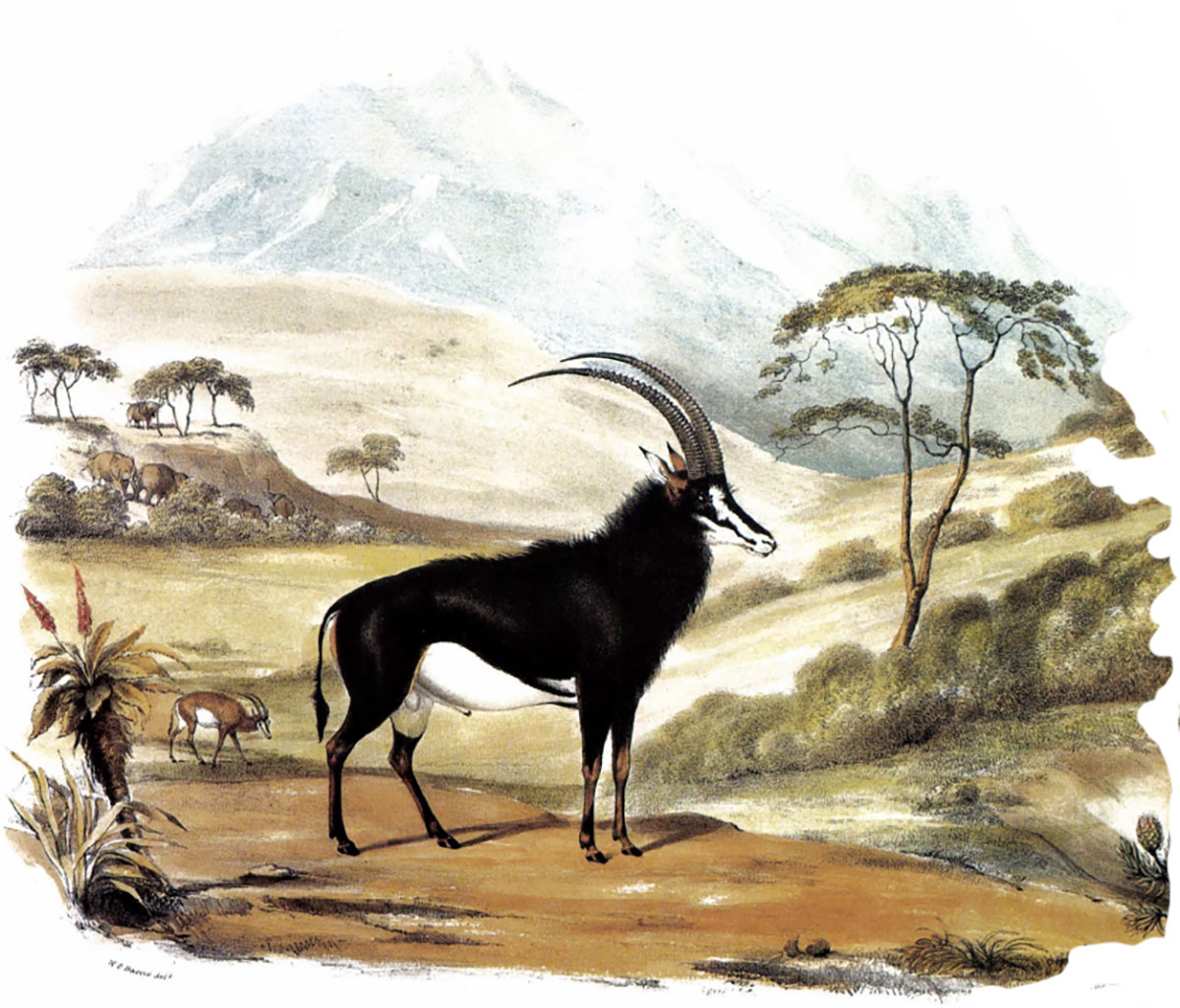

Sable at Mana by Jaco Van Schalkwyk

For a human visitor, Mana Pools is what legendary Africa, shared in family stories and passed down, used to be. It’s a last holdout in a country wracked by political turmoil. Humans who get out of the safe confines of their safari rig and walk—the preserve’s hallmark—are doing it at their own peril. Predators and prey are on equal footing, which arguably heightens the focus of artistic perception.

“Everywhere we’ve gone, we’ve stalked animals as hunters would, but to get the best photographs for research and to convey the vulnerability that exists with the survival of Africa’s most beloved animals—even though sometimes it was quite dangerous,” Van Schalkwyk admits. “I have been the youngster between Ross, David, and Mopho, and fortunately, for the most part they knew what they were doing!”

Those relatively few Americans who have seen the Great Zambezi know it is worth every liquid ounce of the powerful magic ascribed to it. Born unpretentiously—and without drama—in the dambo of Zambia, the river rises westward into Angola and touches upon the border of Namibia. Curving around, it makes a hard turn back again, this time on an ambitious run toward the Indian Ocean, collecting great momentum as it churns through Mozambique.

The Grand Parade by David Langmead

The Zambezi is touched by the shade of miombo subtropical woodlands, ventures near the flanks of the Okavango Delta, then caterwauls over Victoria Falls on its way to Lake Kariba. The fourth-longest river in all of Africa, the Zambezi divides Zambia from Zimbabwe and cuts through rock, savanna, veld, and the strata of time en route to Mozambique, fueling the legends of ancient tribes and weaving together an almost unbelievable assemblage of wildlife and habitat.

“The Zambezi and its tendrils are the lifeblood of the region,” says Parker.

Apart from photographers who have explored the river valley piecemeal, there’s never been a cohesive fine-art interpretation of the watershed as seen through the eyes of wildlife artists.

Impala-Kruger by Jaco Van Schalkwyk

Born in 1981 in the East Rand city of Benoni, South Africa, Van Schalkwyk says he grew up speaking Afrikaans; English is not his mother tongue. During his youth, his religious family made trips to Kruger National Park and his country’s other reserves, but by and large he was a town kid. Later, he spent two years working on a dairy farm where his feelings for nature intensified. As he received fine-art training and an informal apprenticeship with painter Marié Vermeulen Breedt, he started to develop a representational style in which the lines between realism and impressionism were blurred.

Apart from his wildlife work, he’s acclaimed as a contemporary painter who pushes the envelope, using art to address social issues in his homeland and experimenting with an iconography that is a mix of sacred and profane. Part of what makes Van Schalkwyk’s portfolio so intriguing is the contrast between his classic naturalism beloved by sportsmen and women and his corpus of edgier, avant-garde paintings.

Van Schalkwyk has been accepted into residency programs at the Art Students League in New York and in 2013 won a merit award in the Absa L’Atelier competition, earning a stint of study at the Kunst: Raum Sylt Quelle Foundation in Germany. The work that netted him the prize, a provocative painting titled Promised Land, portrays a black South African couple next to a burning field.

Grey Ghost by Mopho Gonde

Unlike many of their contemporaries, Van Schalkwyk and Langmead are not just wildlife documentarians. Their mature perspective is one reason why their work has attracted attention from many museums.

Resonant in both of their works is the dreamy shadow light of Mana, the gallery forests with massive canopies and predators and prey moving through them—elephants, lions, and buffalo skirting waterholes inhabited by hippos and always flanked by the mighty river, a sanguine magnet for birdlife yet just beneath the surface are 12-foot crocodiles that can snatch anything not paying attention.

If Van Schalkwyk’s new lion painting could talk, its brushstrokes would speak to the adrenalin surge that raced through him when, unarmed, he saw the lion’s golden eyes glinting in the sun as the big predator walked toward him. The male and his large 12-member pride had moments earlier taken down a calf elephant, while its frantic, trumpeting mother tried futilely to fend off the swarming circle of felid hunters.

The violence of survival is tempered with Van Schalkwyk’s gentle, respectful interpretation of the aftermath. The humans had heard uproars from the harrowing clash that happened beyond view. After all had gone quiet, the anguished mother elephant had lumbered away, alone. And then, when Van Schalkwyk, Langmead, and Parker assumed they had safely skirted the lions, the simba stepped forward, making certain the intruders had no designs on interrupting the family feast. It approached within feet but let them be.

Langmead, raised on a farm in Zimbabwe, has enjoyed his bush travels with Van Schalkwyk. “He is, first, a good friend with a keen intellect and highly tuned sensitivity to his environment. He is clearly inspired by the African landscape.

“Jaco has mastered his craft superbly and has a mature palette and brushstroke. I love looking at his paintings––discovering the layers of painterliness and feeling his interpretation of things we’ve witnessed together.”

Notes Parker: “David’s been a mentor to Jaco. He’s not only an excellent painter and naturalist, he’s a fearless wanderer.”

Langmead is not interested in portraying African wildlife as a cliché gleaned from viewing subjects behind a long camera lens. He enjoys following tracks and disappearing into the maze of game trails, examining spoor to glean what the animals are eating, and observing wildlife at its most mysterious times—in the edges between night and day.

Second Liaison by Mopho Gonde

Of Parker, Langmead says that few art dealers push the limits of artists in their galleries by putting them in challenging conditions and forcing them to directly observe from nature.

“When we travel to the bush, we are totally at one with our environment,” Langmead says. “It’s a place where we find a common spiritual reinforcement. On one occasion Ross and I spent an entire day in a hide in the Kalahari watching a waterhole, and there were times when we spent several hours in total silence, just absorbing.”

The research expedition to Mana was followed by a recent journey across the river to North Luangwa Park in Zambia. Artwork produced from that mission will be unveiled in 2016.

“Upon arrival in Zambia, I thought this is what Africa must have looked like when the first European explorers and settlers arrived,” says Van Schalkwyk. “Once again the landscape was breathtaking and one got the feeling that its wildlife is still untouched.”

On the way to the park, they stayed at the historical Shiwa Ng’andu Estate. “A true colonial beaut,” Van Schalkwyk says. The 40-room colonial castle was built by Sir Stewart Gore-Browne in the early 20th century and is still occupied by his grandchildren.

“I felt transported back in time and relived the golden days of British colonial life in Zambia,” he says. “A definite must for anyone who wants to make Zambia their next adventure.”

The same kind of Manifest Destiny that swept across the American West, premised on the myth of an endless frontier, is bearing down on the region. “Sadly, our last remaining wildlife areas in Africa are all under threat from the monsters of greed and mindless commerce,” Langmead says. “All the great parks currently exist in a state of nervous apprehension.”

The art that he, Van Schalkwyk, and Gonde create is intended to generate awareness but he admits it will take help from influential collectors to spread the word. In this age of viral technology, outside pressure is what’s needed, and he knows of no group more passionate than sportsmen.

Force To Be Reckoned With by Mopho Gonde

“I am always hopeful that sanity will prevail, and I would encourage international trading partners to persuade the Zambian and Zimbabwean governments to manage the treasure trove of nature in the Zambezi Valley as a much more valuable asset than any finite amount of minerals, fossil fuels, or ivory,” he says. “I fear we’ve reached a turning point.”

As for Van Schalkwyk, his art is already spurring meaningful conversations in Johannesburg and Cape Town. “For me, art that doesn’t elicit a response in its viewers isn’t accomplishing its purpose,” he says. “When viewers see the works we are producing, I hope the subjects give them a single reaction: Awe.”

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2015 Jan/Feb issue of Sporting Classics.

As exhibited in this section of 150 paintings and in Langmead’s absorbing and enlightening text, The Light Fantastic is a transcendental journey, a 20-year love affair between the artist and the beauty of the natural world. For those who have fallen under the spell of the unspoiled wilderness, and those who yet dream of new journeys, wether they be wildlife enthusiasts or travelers, this is a book to treasure.

As exhibited in this section of 150 paintings and in Langmead’s absorbing and enlightening text, The Light Fantastic is a transcendental journey, a 20-year love affair between the artist and the beauty of the natural world. For those who have fallen under the spell of the unspoiled wilderness, and those who yet dream of new journeys, wether they be wildlife enthusiasts or travelers, this is a book to treasure.

The Light Fantastic invites you on a journey into the secret heart of the African bushveld and beyond. Traveler and artist David Langmead has returned time and again to his favorite wilderness areas in passionate pursuit of their sensual beauty. Buy Now