I realized no matter how long I lived or what future hunts might bring, nothing else would ever compare. Such it is when one takes a lion.

It seems customary for those who write about hunting lions to begin by citing influences of others gone before. They will first recall youthful rereads of Patterson, Akeley, Taylor and Hunter, then just as certainly mention the more recent adventures of Mellon, Ruark and Sanchez-Arino.

Metaphoric throat thus cleared, they will hold forth on previous encounters when a lion was not on license, every unsuccessful attempt after a permit was secured and the horrific amount of money unhanded in their quest. Somewhere in the mix will be a recounting of shooting practice, a most careful selection of the professional hunter and, finally, the agonizing wait for their safari to begin. It is with absolute certainty they know the reader will suffer these ramblings, for they are writing of lions and thereby command the floor.

I’ll simply confirm this was the well-worn path I followed and get to it.

I went all in for a lion some years ago, writing the check in anticipation that a permit would shortly open in Namibia’s Kalahari Desert. My reasoning was solid. The Kalahari is a wild place that supports a healthy population of equally wild lions. It is also one of the few areas where lions can be tracked, and I wanted to get close.

For several succeeding years, I was offered the opportunity to hunt with the stipulation that only a younger lion could be taken. Those fully mature types ramrodding prides were off limits. It took some doing to convince those who needed convincing that I was not interested in hunting a young lion or even a pride male. Rather, I wanted to try for a grand old lion, one who had fathered his generations and was no longer associated with a pride.

Professional hunter Jamy Traut holds the hunting rights to a fantastic Kalahari concession and spends a great deal of time keeping track of developments in the region. Frankly, by the time the call came, I had all but given up on ever following a set of those great, splayed tracks. Jamy’s simple declaration that the Namibian Government had designated two old males as problem animals was beyond my ability to comprehend.

“When can you come?” Jamy asked.

What followed was a whirlwind of preparation. For the first time, I took the Kimber Model 8400 Caprivi Special Edition from the vault. The only one ever made, it is chambered in .375 H&H Magnum, making it both ideal and proper.

The red sands of Namibia’s Kalahari Desert afford the hunter the unique opportunity to track a lion. Nothing in the hunting world approaches this level of excitement.

I ordered a set of Talley Quick-Detachable rings and the finest dangerous game scope ever conceived, a Swarovski Z6i 1-6×24. Benched, the rifle consistently put three Federal Premium Cape-Shok Trophy Bonded Bear Claw 300-grain bullets into a ragged hole from 100 yards. More importantly, performance on the sticks was consistently MOA. In a bow to excess, I also acquired a pair of Swarovski EL Range 10×42 binoculars. This selection of equipment proved flawless.

I arrived in Windhoek in advance of the hunt to “assist with preparations,” although I suspected Jamy just wanted me to cool my heels. Several days later we completed the long drive to the Kalahari. Our hosts were waiting and I did my best to follow conversations having little to do with lions. Nothing came up until we were circling the campfire.

“One of the old lions has been frequenting the northern end of the property, although he hasn’t been seen for six weeks,” the ranch manager offered. “His son drove him from the pride some time ago. He occasionally rejoins but is generally alone. I hope he is still out there, and I really hope we don’t find him near the pride. An old lioness among them is frightening, and I’m certain she will come for us if we approach.”

I waited quietly, hoping Jamy would ask.

“Does he have a black mane?” Jamy finally prodded.

“Oh yes, full and black. He’s very big, too, although the years are telling on his weight.”

We outlined a plan to locate the old lion, discover if he was with the pride and then build the hunt around circumstance.

Our group entered the concession at daylight, drove for a bit and bumped a lioness from the two-track. She glowered, then slunk into cover. Window down, I heard excited whispers from the bed of the Toyota, then noticed lion heads popping up all around.

“There’s the male!” someone in back said, so I jumped on the running board and did my best to follow his gaze.

To say he was the most magnificent animal I had ever seen doesn’t begin to describe the lion. He was at least twice the size of a nearby lioness, and through a break in the brush, I finally glimpsed his mane. Coal black and full, it extended well down his back then trailed off to a point behind his shoulder blades.

“Dwight,” someone whispered through controlled laughter, “The big one is over there!”

I went up the side of the Cruiser like a spastic monkey and followed pointed fingers to a thick patch of cover. A nose resolved. Through the binoculars I made out a great muzzle scar, then a golden eye floating in a black pool.

His mane, I realized. That’s his mane!

The moment he stepped clear is burned into my memory, for he was even larger than the first great male. Longer, heavier through the mane and, although noticeably thinner, the thing I had waited a lifetime to hunt.

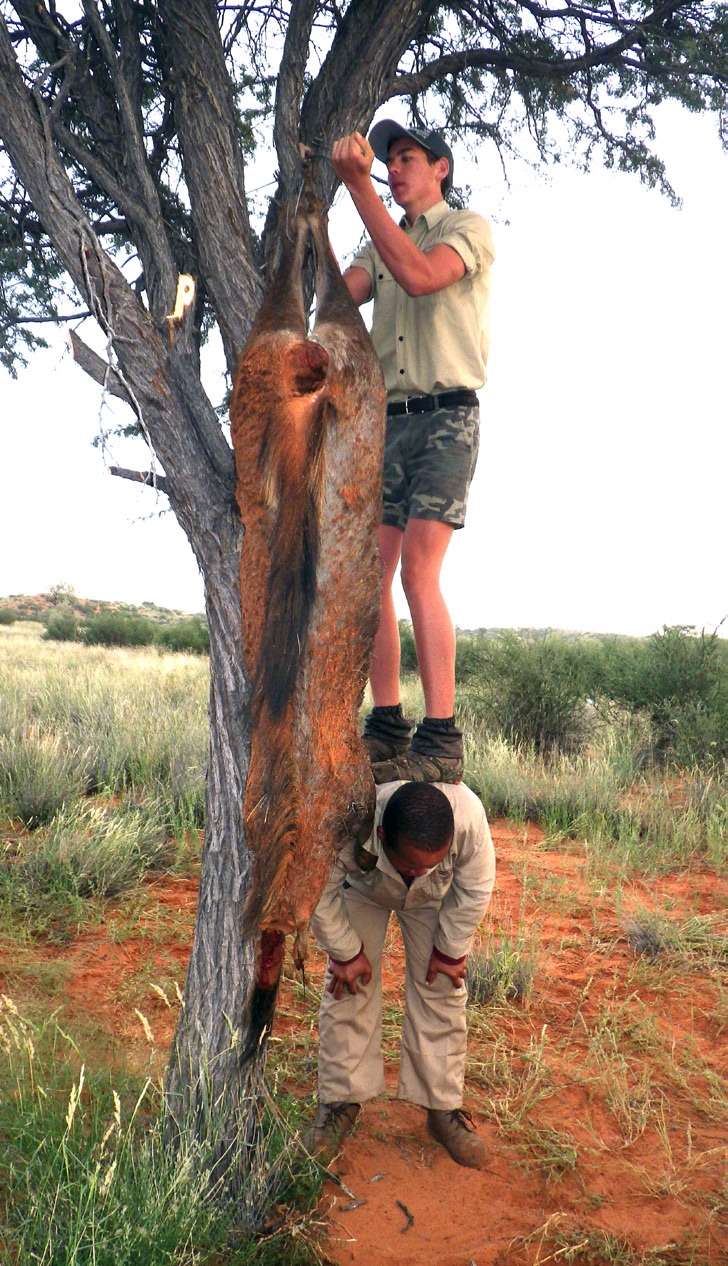

After locating a large pride, Jamy’s son, Nicky and the driver, Harald, quickly teamed up to hang a bait to attract the lions. After determining a very old male was following the pride, the hunt began.

“Let’s move before they catch on,” Jamy said, firing the Toyota. “We’ll return with a bait and draw them out.”

After hanging the best part of a gemsbok in a promising tree, we retreated to a distant dune. Eventually lions showed, the pride male sauntering in and confidently feeding. Sometime later, the old lion turned up, but when he approached the bait, the younger male attacked and drove him away.

Back in position at daylight, no lions were evident and the gemsbok was gone. Moving closer, we discovered the old lion watching from a pocket of dense brush and guarding the picked-over bones.

The sun was high by the time we satisfied ourselves that the pride had left the area. We then tried a stalk, but there was not even the slightest chance for a shot. The lion broke cover at speed and didn’t stop for a long time. Tracking, we found him again that afternoon with much the same results. After discovering a huge track by flashlight the next morning, we backtracked for three miles to see if it was the right one, for it would be him or nothing. Once certain, we turned back and followed the track for a dozen miles before glassing him bedded near the top of a dune. The approach was perfect, but when we crept over the top, he was already 300 yards away and going flat out.

Back on the track, it was well into the afternoon before we saw him in the distance.

“He’s calming,” Jamy whispered, “looking for a place to rest.”

We began another approach, with Jamy eventually indicating the lion was meandering about in search of a bed. Creeping now, I stayed in Jamy’s hip pocket until he hit the ground.

“Right there,” Jamy pointed.

The lion was lying in the shade of a shepherd’s tree about 80 yards away. From Jamy’s motions, it was evident he was alert.

“Crawl,” came the command.

It took us 20 minutes to gain 30 yards, as we didn’t have much cover and Jamy would move only when he thought the lion was looking away. Finally, Jamy signed that the cat’s head was down.

“Calm,” he mouthed.

I didn’t know if he meant the lion, if he was asking me a question or giving me an order.

Jamy rose and positioned the shooting sticks. I followed, set the rifle and found the lion. He was still for an instant, then turned in our direction. As he stood I broke the trigger. The lion whirled twice, roaring, took several great bounds and fell.

At least 11 years old, broad through the muzzle and with a tremendous black mane, the lion was so spectacular he remains beyond my ability to describe or comprehend. We carefully skinned the great cat, then prepared the meat for distribution to the locals. Through a fog, I realized that, no matter how long I lived or what future hunts might bring, nothing else would ever compare. Such it is when one takes a lion.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt, Markham – the legends in outdoor literature are all here, sharing their stories of deadly encounters with dangerous game, of bizarre run-ins with witch doctors, gorillas and man-eaters, of safaris into the uncharted wilds of deepest Africa.

Illustrated by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Shop Now