“This is the kind of bear George wanted me to find,” I managed. “This bear is more his than mine. Always will be.”

It would not be even the slightest untruth to declare that the friendship I am fortunate to share with George Butler was born of chance and solidified through a progression of odd circumstances. Of course, many relationships follow a similar path. What makes this tale worth telling is the tremendous adventure it has added to both of our lives.

I sell guns for a living, mostly fine sporting arms entrusted by collectors and estates. One of these, a double rifle, captured George’s attention. Following an exchange of particulars, he anxiously took delivery and soon reported back with initial satisfaction. That was that, or so I thought.

George phoned several weeks later with a range report. Being a talker, a common affliction of those hailing from Mississippi, he eventually swung the conversation from guns and hunting toward the personal. George was acting as the principal care provider for Bonnie, his wife of many years, and shared some highlights of their wonderful life together.

“I’m right there with you,” I somehow managed to interject. “My mother is also in failing health, and every evening is dedicated to helping my father make her as comfortable as possible.”

From then on George and I were in touch nearly every day, usually visiting about our common challenges and interests. George and Bonnie never had children, so he was always quick to prompt discussion about my son and daughter. When my mother passed away, George was the first to send flowers. When my son announced that I was soon to be a grandfather and my daughter’s wonderful boyfriend asked me for her hand, George was among the first to hear the happy news.

My granddaughter, Annabel, came into the world on the heels of an October blizzard, and Bonnie slipped away hours later as we were fighting our way home. It took some time before I could find a safe place to pull off the highway and make the call. George made it easy, continually steering the conversation away from his sadness to the tremendous joy he knew my family was experiencing.

Several days later I invited George to fly out to Montana and tag along on a weekend hunt. To my surprise, he accepted, and it wasn’t long before he greeted me at the airport with a crushing handshake. I showed him some wonderful country, and George was right there when the finest whitetail buck I’d seen in years gave me the slip. Naturally, I assigned him all the blame.

George was quick to fall in love with Montana, but what he really longed for was Africa. His desire to go on safari burned as strong as any I’ve ever seen, so it didn’t take too much convincing to get him to join me at the Safari Club International Convention a few months later. He took it all in, and then booked his first safari, a plains game hunt in Namibia, with my favorite Professional Hunter, Jamy Traut.

George touched down in Windhoek several months later. The stars rightfully aligned, and he took a full bag highlighted by a tremendous kudu bull. Not long after returning he contacted Jamy again and grabbed the first opening for Cape buffalo in the Caprivi Strip. By just about any standard, the solid-bossed whopper of a bull he shot through a window in the tall grass was grand. For Namibia, it was spectacular.

George bought his own little piece of Montana the next spring, a little cabin not far from my home. He then established a routine of coming out from Mississippi as often as possible. Now fully a part of my family, he joined us for nearly every outing and celebration. Granddaughter Annabel began to call him “Bad-Bad George” for reasons only she could determine and much to his delight.

Late last winter George mentioned that he really wanted to go on a bear hunt, so I began researching options and found what appeared to be a wonderful opportunity for black bears on Vancouver Island. This particular camp was full, but a final slot was offered at auction. George bid high, but someone wanted it more. He took the news well, and then remarked, “I’d rather hunt Alaska, anyway. How about you put me in touch with Dave Leonard? You always speak highly of him, and anyone who can get your sorry ass an Arctic grizzly ought to be able to find a big Peninsula brownie for a real hunter like me.”

I happily did as instructed and discovered Dave had a cancellation for the spring season, just weeks away. George jumped on the chance like a chicken on a June bug, then flew off to Mississippi and began preparations.

Helping George order gear and make other arrangements became something of a full-time job, but I was glad to do it. So when he called one afternoon, I naturally assumed he wanted to go over more details. Instead, his words hit like a sledge.

“I went to the doctor this morning ’cause I’ve been feeling a little rough in the guts lately. I didn’t say anything because I didn’t want anyone to worry. Anyway, they put me under and did a test. I’ve got cancer; stage four. Things don’t look real good.”

The next few days were a whirlwind. George talked more with his doctor and also consulted a specialist. My family and I researched frantically in an effort to help him plan the best course of treatment. At first, George remained determined to go to Alaska, then changed his mind and asked me to sell the bear hunt.

“You know the kind of people who might be interested, even on short notice. Do what you can to find someone else. I still feel like I can go, but two weeks in the middle of nowhere might change that, and I don’t want to worry Dave or put anyone at risk in case I turn sick.”

I honestly believed George would change his mind, though I pulled out all the stops to turn up a replacement. I struck out. It just wasn’t possible to find someone who could make the necessary scheduling adjustments.

The David River base camp provides all the comforts of home in this vast, lonely land.

Dave Leonard phoned about three weeks before George was slated to leave.

“Dwight, I just got off a call with George. He’s made up his mind and wants you take the bear hunt. We’ve discussed all his options, and I’ve even offered to try to get him a bear from base camp, but he’s worried all that would be too much of a burden. Can you clear your schedule?”

Promising to get right back, I immediately called George. We went over everything two or three times until nothing was left to discuss. Then we flat argued about it, me thinking some pressure might prompt him to give it a try. His mind was made up.

“Dwight, I figure someone ought to go who has a chance of remembering the hunt for a long time. It wouldn’t be right for me to shoot a bear and then maybe not be around when it comes in from the taxidermist. I know you and understand how much you’ll enjoy the trip. Please, let me do this in appreciation for all you and your family have done for me.”

Choking on emotion, I mumbled something of a preliminary thanks, accepted and then called Dave back to set things in motion. I held on to a faint hope that George would step back in, right up to the morning I drove to the airport.

Dave Leonard’s outfit, Mountain Monarchs of Alaska, hunts the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, possibly the best big bear country in the state. It is a wild land, little changed since John Eddy explored it in the early days of the Great Depression and then chronicled it in his book, Hunting the Alaska Brown Bear. Eddy wrote well of it, with vivid descriptions of magnificent valleys crowned by spectacular peaks and of the “Big Brown Bear” that broke out of their dens and lumbered across vast snowfields.

Basing from the David River Bear Camp, established by Dick Gunlogson in 1971 hard on the Bering Sea shore, Dave shuttles hunters to spike camps that have proven themselves time and again. Once there, hunters anchor tents against the tremendous winds and then glass pristine valleys and huge mountains, hoping to catch a glimpse of a big boar lumbering in their direction.

As it was, hunters were weathered in at base camp for two days, and when the sky finally cleared, Dave frantically began flying everyone out on what should have been their first hunting day. I pulled Dave aside between shuttles and told him to get all the other hunters and their guides out first.

“Take care of everyone else,” I remember saying. “George is here with us in spirit, and I have a feeling that everything is going to work out accordingly. In truth, I think it is going to be magical.”

The following morning Dave and his wingman flew my guide, Todd, and I to the most beautiful Alaska valley I’ve ever seen. When we landed I asked where we were. His answer chilled right to the bone. Described in vivid detail in Eddy’s book, it was the very place I first read about as a boy and had dreamed of hunting ever since.

Hunters and guides are shuttled via Super Cubs to proven spike camp locations.

“This is a fantastic spot,” Dave continued. “One of my hunters took a boar that squared over ten feet right there,” he said, pointing to a patch of alders not 400 yards away. “Another shot a ten-six in almost the same spot. Be patient, and it’ll happen. This valley is always full of bears.”

We quickly unloaded and piled a mound of gear at the side of the strip. Dave hurriedly climbed back into his plane, then motioned me over. Rather than wishing good luck, he took my hand in his and softly said, “For George.” Then he was gone.

Todd and I shuttled gear, spread the tents in a low spot that promised some protection from the winds, and then staked them down with enough line to anchor a circus big top. Once everything was sorted we took on a quick dinner, then hurried to Dave’s recommended overlook and began glassing, knowing full well that Alaska’s same-day airborne law meant I couldn’t put my rifle to work.

It wasn’t long before we were looking at a giant. The nearly black boar must have been lying in one of the many wrinkles in the valley floor, as he simply appeared where moments before there was nothing.

“That’s a good one,” Todd hissed, “the kind we’ve come here to hunt.”

Swinging his great head from side to side as if deciding which way to go, the bear eventually began to work across the valley. His hind legs first swung out and then around his great belly in the awkward sore-footed stride of the largest boars. In the spotting scope, he looked short-legged and small-headed. His thick fur ran riot, shooting arrows from the sun’s reflection and rippling in the evening breeze.

“I wish George was here,” I whispered, as much to myself as to Todd. “He’s never seen anything like this place, or that bear, and this moment would have made his entire trip worthwhile.”

We watched the bear for a long time as he crossed the valley, climbed a mountain and then disappeared. I wondered if we might see him again another day and how many times Eddy had watched and then wished the same thing just as hard all those years ago.

Another bear showed on a distant, snowy face, quickly morphing into a sow with a pair of yearling cubs. Evening must have been playtime, for they spent two hours alternately climbing and sliding, the cubs wrestling on the way down and playing an enthusiastic games of tag on the way back up. The sow eventually joined in, rolling on her back and tobogganing down tail first with one of the cubs cradled on her belly. I couldn’t help but think how this might be one of their last days together, as the rut was coming on and they would likely be separated for good when a suitor appeared.

“Watching them makes me think of the friendship I have with George,” I observed softly, the words more a stream of consciousness than meant for Todd. “I like things just the way they are and wish I could keep them that way. Those bears are lucky. They can’t hear the footsteps of coming change, and simply live in the moment.”

Todd and I were in the glass by first light the next morning, and it wasn’t long before we began checking off bears. The sow and her cubs showed first, then two medium-size boars appeared on opposite sides of the valley. One was lazing near the mouth of a den he had kicked open during the night, and the other was on the move. Neither came closer than two miles, but watching them prompted Todd and I to discuss expectations.

“I’m hoping to find a bear for the ages,” I began, “a grand old boar that takes my breath away at first glance. The kind of bear that would make any hunter proud. This one isn’t for me. It’s for George, and I want to do right by him. I’ve got a strong feeling it’s going to happen, and I want to savor every moment so I can take it all back and tell him the story.”

Todd and I kept loose track of every bear we spotted. When darkness shut us down the tally stood at 15. While none had been a contender, it was clear that the rut was on and that we were in the right place. Sleep came easily, and getting back out the next morning was effortless.

Weather was with us that day, clear and warm. By the time the sun was overhead at least six bears had come and gone. Todd was watching as one worked along a distant patch of snow, then told me to take a look.

“There’s a big bear following that sow. I saw him just as he ducked behind some rocks, but he’ll be back on her trail soon.” I was set up by the time he reappeared.

Even at two miles, it was obvious the boar was special. He had the waddle-walk, extended stride, and small head that betrayed great size.

“That is the type of bear you described,” Todd said softly. “Very big. Ten-plus for sure.”

This caribou may have fallen prey to one of the bears the author observed hunting.

There was only a slim chance, but we were both anxious to give it a try. After shedding as much gear as possible, we climbed up and out of the valley then moved along the main ridgeline, hoping to intersect the pair. Slowed by an alder hell, it took at least an hour longer than expected to get where we wanted. The bears were long gone, their tracks angling across the top and down the other side.

“Maybe one of Dave’s other hunters will see them coming and have a chance,” Todd said in that positive tone of the best guides. “One of our guys is camped about five miles out in the direction they’re headed. Anyway, lets stay here a bit and see what turns up.”

We gave it an hour, as much to rest as to take advantage of the elevation. Several more bears showed in the distance, though nothing of size. When the sun drifted close to the horizon, we backtracked and made it back to the tents right at dark. The Mountain House tasted great and the Tang even better.

Clouds blew in from the ocean early the next morning. The flat light made the bears more difficult to spot, or maybe they just weren’t moving as much. We counted eight, but after seeing more than a dozen each of the first two days, things seemed slow.

The weather cleared for a couple of hours that afternoon. As it did the clouds lifted to reveal a big boar ambling in our direction.

“He’s pretty good, just under ten feet, but he’s young. Better chamber up in case he decides to come see if you’ve got anything worth eating in your pack,” Todd ordered.

Changing course a bit, the bear passed just below and then set a course for a boulder standing vertically in the middle of an open area to our front. He first sniffed it intently, then spent the next few minutes rubbing against it, mouth open in an expression of sublime relief.

“George would take that bear,” I volunteered. “He’s big and beautiful. Equally important, he’s right there!” It would have been an easy pack, too, just over 100 yards to the strip.

Not long after, another boar crossed three miles up the valley. If anything, he was bigger than the first and might have made ten, but distance kept him safe. The wind picked up and rain began to fall, pretty much a normal day in May for the Peninsula. We stayed at it several more hours, kept company by a few rough-looking caribou cruising around in their constant search for food.

The author prepares for follow-up shots, but after three .375 rounds, this bear was down for the count.

We didn’t see many bears the following morning, but a good boar spent most of the day chasing caribou around near the head of the valley. A good four miles away, we watched him sneak in on several small bands. We had already decided to try a stalk if he managed to pull one down, but luck wasn’t with him. By the time we were back at camp, it was evident that the weather was taking a turn for the worse.

“Tomorrow might be tough for glassing,” Todd warned. “Out here, storms usually hold on for two or three days. The fog gets thick and comes right down to the ground. If that happens, we won’t be able to see fifty feet.”

For some reason I’ll never understand, I wasn’t worried.

“I guess we’ll just roll out at the regular time and see what happens,” I replied. “At least it isn’t really cold or snowing, and if things get bad we’ll come back for a nap. For sure, we can’t hunt from our sleeping bags.”

It was dark long into morning. Thick fog cut visibility dramatically, sometimes to the point that a bear could have walked right by without being seen. The wind was strong, occasionally opening a hole here and there. When it did we would frantically wipe the water off our binoculars and scour the open patch until it shut back down. The first bears of the day didn’t show up until late in the afternoon when a little sow led her cub across the valley just behind camp.

Evening found us hunkered down against driving rain, hoods pulled down tight, as much to protect our faces as to keep the water off tripod-mounted binoculars. Todd even put his spotting scope back in his pack, for it was all but useless in the fog. For the first time, we were getting cold and miserable, but we stuck it out.

As much to keep warm as anything else, Todd and I alternated walking over to a point where it was possible to look down the valley. Conditions were so bad that binoculars were useless. All we could do is stand there and look for brown spots, so I was surprised when Todd came running back and tore open his pack to get at his spotting scope.

I jumped behind him to gain his line of sight, then threw up my binoculars just in time to see a bear clear the alders.

The author and his . . . George’s brown bear.

“I think . . . that’s . . . yeah, that’s a good boar,” Todd hissed. “Solid ten. Take a look.”

I leaned into Todd and took a quick look, managing to watch the bear take two steps before the rain soaked the lens.

“He’s big. Let’s go,” I responded quickly, rolling away and reaching for my rifle.

The boar was 600 yards away, on the other side of the valley’s pinch point and moving down. We ran to keep the wind in our favor, stopping twice to relocate him and adjust our course accordingly.

I got my first good look at the boar when we were 300 yards out as he moved slowly through an opening. His forehead had the sharp slope that comes with age. His walk was stiff, almost arthritic, and his chin ruff was long and scalloped like those in a Rungius painting.

“I want that bear,” I whispered. Quite possibly, those were the most unnecessary and superfluous words ever uttered by a hunter.

We closed the distance until cover gave out, and when the boar walked into the open Todd set the range at 179 yards. I was already prone over a pack and triggered the .375 H&H. The bullet smacked the point of the shoulder, dropping the bear almost completely out of sight in the grass. He tried to rise moments later, and I followed with another in the same spot, then stood and fired again to be sure.

“George is going to be thrilled with this bear,” I whispered to Todd. “Thanks for making this such a wonderful hunt.”

I topped off the magazine before we approached, Todd insisting that we watch for a bit to make sure it was safe. The bear seemed to grow larger with every step, and when I finally knelt down next to him, no words would come.

“He’s a solid ten for sure, maybe a lot more,” Todd said with clear admiration. “Really old, too. Look at the wear on his teeth.”

“This is the kind of bear George wanted me to find,” I managed. “This bear is more his than mine. Always will be.”

Even with an early start, it took us almost all of the next day to get the bear skinned and packed back to camp. With an 80-pound pack, it was a struggle for me. How Todd managed the tundra with twice that on his back is beyond comprehension.

Dave picked us up the next day, and it was something of a show to watch him wrestle all that bear into his Super Cub. Once at base camp, he offered the satellite phone so I could call George. I held off, mostly because I knew George would want to know just how big of a bear I was bringing home.

Some of the other hunters had already taken their bears and departed, so Dave put three guides to work fleshing and cleaning the skull. Once done, proper field measurements would be taken.

The brown bear’s huge cape, which squared 10 feet, 10.5 inches, towers above (l-r) guide Todd, the author, and outfitter Dave Leonard.

I flew out the next day, and just after landing in Anchorage my phone rang.

“Dwight, this is a very big bear,” Dave began. His skull is right at B&C, and the hide squares ten feet, ten and a half inches.” The rest of the conversation is gone, for all I could do is stand there in the rain and cry.

As soon as I recovered, I called George. He answered with the enthusiasm of a boy on Christmas morning.

“Get him?”

“Sure did, my friend. An old monarch, bigger than I ever dreamed possible and far better than I deserve.”

“I’m so happy for you. Now, get your ass home and show me some pictures!”

“I’ll be there late tomorrow afternoon, in time for dinner. See you then.”

As soon as the call clicked off, I cried again for a very long time.

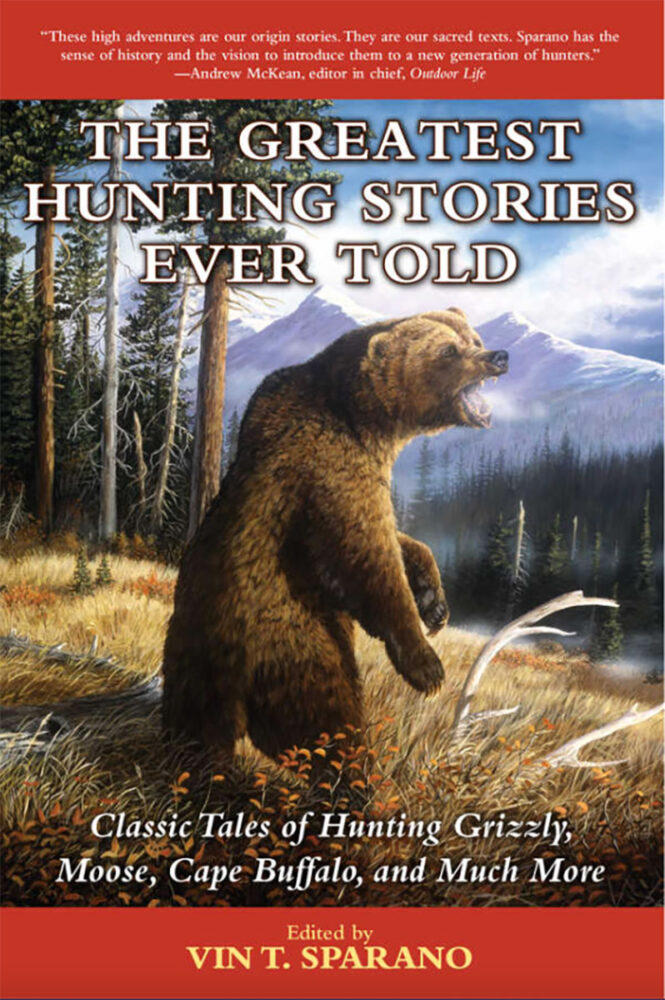

Collected by a lifelong devotee of hunting literature, the stories here are classics. In more than two dozen selections, the true experiences of hunting a variety of animals are relayed by the most reliable eyewitnesses: the hunters themselves. A must for all hunters and armchair adventurers, The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a real trophy. Buy Now

Collected by a lifelong devotee of hunting literature, the stories here are classics. In more than two dozen selections, the true experiences of hunting a variety of animals are relayed by the most reliable eyewitnesses: the hunters themselves. A must for all hunters and armchair adventurers, The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a real trophy. Buy Now