WHERE DID THE .25-06 REMINGTON COME FROM?

Both the .25-06 Remington and .270 Winchester were created by necking the .30-06 case to hold narrower bullets, .257-inch and .277-inch, respectively. That’s not a massive difference in diameter, but .257 bullets top out at about 120 grains and .277 bullets at 150 grains, with a few now made as heavy as 180 grains. On the light end, .257s will go as low as 60 grains, the .277 down to 90 grains. All this suggests the .25-06 is optimized for deer-sized game down to coyotes and rock chucks. The .270 may be a bit much for varmints but is perfect for deer and adequate for elk and even moose.

Of course, plenty of those animals and larger have been taken with the .25-06, too, but then the same can be said of the .223 Remington. What we really need to know is how the .25-06 Remington stacks up against the .270 Win. and similar “mid-size” deer hunting rounds like the 6.5 Creedmoor.

You may be surprised to learn that the original .25-06 popped onto the radar years before radar was even invented. It was 1920 when gunsmith A.O. Niedner gifted it to the public as the 25 Niedner. Cartridge designer Charles Newton had actually beaten Niedner to the punch with a .25-caliber version of the .30-06 case about 1915, but he perfected it as the shorter .250-3000 Savage. (More on that later.) All Niedner did was neck down the .30-06 to hold a .257-inch bullet. He chambered it in a variety of single-shot rifles, so it was seen as a long-range varmint cartridge first, a deer round second. Shooters loved it, but since no mass-produced rifles were chambered for it nor factory ammo loaded for it, popularity never approached that of the .270 Winchester, released in 1925.

Also working against the 25 Niedner was another .257 wildcat that hit the shooting scene in the 1920s. This was the .257 Roberts, based on the 7x57mm Mauser case hitting about 3,300 fps with an 87-grain bullet.

The Roberts leaped to the top of the .25-caliber pop charts because in 1934 Remington released their version of it, wisely keeping the already established .257 Roberts moniker. With factory ammo and rifles readily available, it took off, aided by its flat trajectory and mild recoil.

MORE .25-CALIBERS THAT COMPETE AGAINST THE .25-06 REMINGTON

As if that weren’t enough to steal market share from the 25 Niedner, let’s not forget the .250-3000 Savage (which most of us do these days). That cartridge had ignited a firestorm of shooter interest in 1915 when it became the first commercial rifle cartridge to break the 3,000 fps speed barrier. It did so by throwing a light, 87-grain bullet. I don’t know what the 25 Niedner was churning out at the muzzle in those days, but the .25-06 Remington today routinely hits 3,500 fps with an 87-grain bullet, suggesting the Niedner wildcat was the speed champ in the 1920s.

In those days the only other .257s that could even remotely steal customers away from the Niedner were the anemic .25-20 Winchester and .25-35 Winchester. Both were geared for lever actions with flat- or round-nosed bullets poorly designed for ballistic efficiency, and neither round left rifles with excessive speed to begin with.

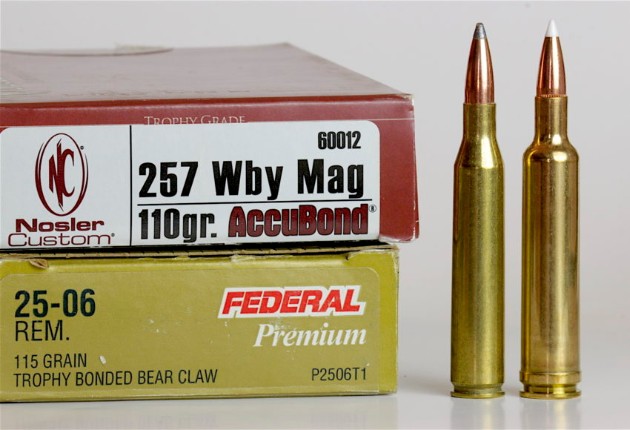

Still, five different .25 calibers focused a lot of shooter interest in the quarter-bores from 1915 through the 1940s. They were so popular that Roy Weatherby joined the race in 1944 with his .257 Weatherby Magnum, still the fastest .25 caliber in the stable. It probably shot out of the blocks at 3,700 fps with an 87-grain bullet. But you had to buy an expensive Weatherby rifle or build a custom to shoot it.

The 25 Niedner faced a similar challenge. No major manufacturers loaded it or chambered rifles for it. Another reason typically offered to explain the languishing 25 Niedner is that powders of the day didn’t truly let this round breathe. They were too fast-burning to optimize velocity with heavier, more ballistically efficient bullets and those seen as appropriate for bigger deer, bear and elk. Most 25 Niedners were probably shot with 87- to 100-grain bullets.

The larger, faster .257 Weatherby Magnum became a factory cartridge more than 20 years before the .25-06 Remington was finally given legitimacy.

THE 25-06 REMINGTON IS FINALLY LEGITIMIZED

It wasn’t until humans first landed on the moon, in 1969, that Remington finally released the 25 Niedner as the .25-06 Remington we know today. By that time it had come closer to its full potential, thanks to the advent of slower-burning powders. Today is shines under the power of some of our slowest powders like Retumbo and Magnum.

According to Nosler’s Reloading Guide 7, the .25-06 can push an 85-grain Ballistic Tip 3,600 fps and a 100-grain Ballistic Tip 3,360 fps. It’ll drive a serious big-game bullet, the 120-grain Partition, at 3,175 fps through a 24-inch barrel—and probably an elk.

Take on a bull elk with the .25-06 Remington? Put the right bullet in the right place and you’re eating all organic.

Folks, 3,175 fps is fast. Our beloved .270 Win. doesn’t quite hit that velocity with a 130-grain bullet. Zero both 2½ inches high at 100 yards and they’ll land within a quarter-inch of one another at 400 yards. Wind deflection favors the .270 Win. by a lousy inch. The .270 will carry 200 f-p more energy than the .25-06 bullet, but I’ll predict no deer or even elk is going to notice. In other words, tie game.

So, why is the .270 Win. still so much more popular? Undoubtedly because it had such a huge head start and has gotten so much press over the years. But that’s no reason for serious riflemen and women to ignore the .25-06. If you’re shopping for a mild-recoiling, flat-shooting cartridge for whitetails, mule deer, blacktails, antelope, sheep, mountain goats, black bears, caribou, coyotes, wolves and long-range varmints—with enough oomph for elk and even moose if you place your shots carefully—don’t overlook the .25-06 Remington. (This YouTube video shows the flat trajectory of a 100-grain .25-06 Remington and its “knockdown” effect on a pronghorn.) And if you’re still not convinced, keep reading . . .

A sporter-weight bolt action like this stainless-synthetic Sabatti Rover 870 in .25-06 Remington is bound to make pronghorn hunters smile.

.25-06 REMINGTON VS. 6.5 CREEDMOOR

This brings us back to the 6.5 Creedmoor. Everyone is gaga (ladies included) over this cartridge because it supposedly shoots far and flat with minimal wind deflection and mild recoil. The Creedmoor will shove a 143-grain ELD-X bullet (BC .625) out the door going 2,750 fps, according to the Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, 10th Edition. Zeroed 2½ inches high at 100 yards, it peaks 2.6 inches high at 150, falls 5 inches low at 300, and 17.6 inches low at 400. Wind deflection at 400 would be 7½ inches and remaining energy 1,621 f-p.

In an eight-pound rifle, recoil velocity should be 10.7 fps and recoil energy should bump your shoulder with 14.3 foot-pounds of energy. Sounds great, eh? But let’s see what the old .25-06 Remington can do.

One of the highest BC .257 bullets on the market is the Berger 115-grain Match Grade VLD Hunting at .466 BC. The Berger Reloading Manual 1st Edition indicates the .25-06 in a 26-inch barrel can drive it 3,149 fps. Nosler gives 3,170 fps for its 115-grain Ballistic Tip from a 24-inch barrel, so let’s compromise at 3,150 fps.

Zero the Berger 2½ inches high at 100 and it’s 3.1 inches high at 150, 1.8 inches low at 300, and 11.1 inches low at 400. Wind deflection at 400 is 8.6 inches, remaining energy 1,572 f-p. Recoil velocity in an eight-pound rifle would hit 11.4 fps, recoil energy 16 f-p. For felt recoil perspective, a .270 Win. would hit 12.7 fps and 20 f-p.

To make this data easier to compare, let’s make a trajectory chart and include the .270 Win. All cartridges are zeroed 2½ inches high at 100 yards and fired in a 10 mph right-angle wind at 50 percent humidity, 590F at 5,000 feet above sea level. Drop is in inches, Drift in inches, Energy in foot-pounds.

How surprising is this? The unheralded .25-06 Remington actually shoots flatter than both the .270 Win. and the 6.5 Creedmoor. The Creedmoor, thanks to its much higher BC bullet, deflects less in the wind, but only by 2½ inches at 600 yards! The light .25-06 bullet loses in the energy department, but I’ll bet it’s not going to bounce off of a deer’s side at 600 yards. If you buy into this “minimum impact energy” theory (that you need at least 1,500 f-p impact energy to kill an elk), you’re good out to 400 yards with a .25-06 Remington, and there are plenty of loads on the market.

High BC, low-drag bullets are optimized in 6.5mm (.264) caliber, but not yet in .257. Nevertheless, the .25-06 shoots flatter than the 6.5 Creedmoor and deflects just one inch more in a ten mph wind at 400 yards.

WANTED: HIGHER BC BULLETS FOR THE 25-06 REMINGTON

You can alter these ballistic numbers by playing around with different bullet weights and BCs, but the three covered here represent some of the highest in their respective calibers, and that bring up one potential “upgrade” we could make to bring the nearly 100-year-old 25 Niedner/.25-06 Remington into the 21st century: higher BC bullets.

Nobody is making a sleek, long, heavy-for-caliber, high B.C. .257 bullet. Hornady, Nosler, Barnes, Cutting Edge, and others are pushing .277 projectiles into the .6s. Berger now has a 180-grain .277 bullet rated .662 BC! Just about anyone else who makes a bullet churns out 6.5mm projectiles with BCs in the .6s. Heck, they’re even making long, heavy, skinny .243 bullets with BCs approaching .50. Yet the .257 languishes. I’ve yet to find a .257 bullet that even breaks .5 BC.

There are lots of great .257 bullets on the market, many pretty sleek and slippery. But there are no truly modern, heavy-for-caliber, extremely high BC models. Their time has come!

Why? Probably because there are no long-range competition cartridges designed around the .257 bullet. That’s what drives the 6.5mm and 6mm high BC race. The .277, however, isn’t a competition caliber, so that one must be driven by long-range hunting. So why not the .257? Probably because standard barrel twists (1:10) are insufficient to stabilize projectiles much longer than current offerings. But that applies to many other calibers and cartridges that are getting high BC bullets. Shooters can and do upgrade to fast-twist barrels. That’s the wave of the future.

For more from Ron Spomer, visit his website, ronspomeroutdoors.com, and be sure to subscribe to Sporting Classics for his features and rifle column.