Last week we ran a story extolling the virtues of the .243 Winchester. But how does it stand up to a legendary deer-getter like the .30-30? Read on to find out.

The sun was on the Nebraska horizon and a Mossberg .243 Winchester bolt action was on my shoulder when a herd of November whitetails exploded from a copse of trees and scattered into the Sandhills. Flashing tails, leaping legs, long necks, and there! Antlers! Wide, tall, oh-man-he’s-a-big-one, and he’s getting away.

Like every whitetail, he raced for the horizon, showing no signs of stopping. I sat anyway, spread my shooting sticks, bolted a Ballistic Silvertip into the little rifle and prayed. Stop.

She did. The buck hadn’t been running from me so much as running after an estrus doe. In the confusion of flight, she looked back for the rest of her herd. Wither she stoppeth, he stoppeth. Three hundred eighty seven lasered yards, dark against the hillside, antlers like a halo. It was a big job for a 95-grain bullet. Was the .243 Winchester up for it?

As hunters and riflemen, we might want to reassess some of our assumptions, because they’re probably based on hearsay, tradition, superstition, folklore, or myth. Put simply, we’ve heard it so many times that we believe it. And repeat it.

This is why so many hunters think a .243 Winchester is too puny to kill a deer. No one told that Nebraska buck.

A forked G2 and broken brow tine on the right antler stood between this buck and B&C.

So let’s check some hard numbers for enlightenment, starting with the often repeated minimum-energy standard for termination of an average whitetail: 1,000 foot-pounds of energy. How this number was chosen I do not know, but it is widely accepted, ignoring the thousands of deer, perhaps millions, poked with arrows and poached with .22 Long Rifles. A typical high-velocity, 40-grain .22 LR hollow point generates about 140 f-p of energy at the muzzle, 100 f-p at 100 yards.

But let’s forget the .22 LR and focus on a famous whitetail killer—the .30-30 Winchester. This is widely regarded as the greatest deer round in history, responsible for putting more venison on the ground than any other cartridge. Virtually every deer hunter agrees it is deadly at 150 yards, more than adequate at 200 yards if you can hit what you’re aiming at.

Similarly, the .308 Winchester is regarded as a decided improvement over the .30-30, since it throws the same .308-caliber bullets, but much faster. Meanwhile the poor little .243 Winchester, which is the .308 Winchester case necked down to accept .243-caliber bullets, is suspect. Too little. Too weak. But is it?

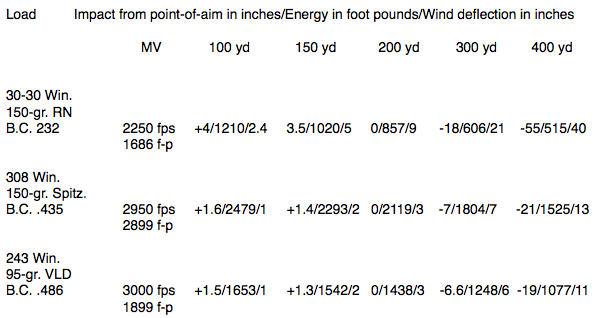

Let’s run some ballistic trajectories on each of these, using popular deer-hunting bullet weights as examples. We’ll zero each rifle at 200 yards to get a fair picture of trajectory curves. We’ll fire all of them in the same weather conditions—calm and 65 degrees Fahrenheit, with a 10-mph right-angle wind.

From this little comparison you’ll note some eye-opening numbers, especially between the .30-30 Win. and .243 Win. The .243 Win. starts with a bullet weighing 55 grains less than the .30-30, but its additional 750 fps muzzle velocity gives it 213 f-p more energy at the muzzle. This is because doubling a projectile’s weight doubles its kinetic energy, but doubling its velocity quadruples its kinetic energy. The joys of physics.

Trajectory and energy tables indicate the .243 Winchester isn’t the 95-grain weakling some make it out to be.

Something else enlightening is retained energy downrange. At 150 yards, the 95-grain .243 bullet is hauling 522 f-p more energy than the much heavier .30-30 slug. At 400 yards, the puny, ineffective .243 is still packing more punch (1,077 f-p) than the .30-30 at 150-yards, what many consider “dead deer” distance for the famous .30-30. How did that happen? B.C.

Ballistic coefficient, or B.C., is a numerical rating that reflects a projectile’s ability to minimize air drag and retain velocity/energy—two sides of the same coin, according to Einstein. Note the B.C. of the .243 bullet listed above. It is more than double that of the .30-30 slug. The short, stumpy, round-nose form of the .30-30 wastes its energy pushing air. The long, sharply pointed, sleek, boat-tailed shape of the Berger Very Low Drag .243 bullet minimizes air drag.

You might also notice how the .243 deflects less in the wind than not only the .30-30, but even the 150-grain .308. This runs counter to another popular misconception—that heavier bullets drift less than lighter ones. It isn’t bullet weight but B.C. and velocity that influence wind deflection. Weight is part of B.C., but so is form. As long as two bullets start with the same muzzle velocity and have the same B.C. rating, it doesn’t matter how heavy they are. They deflect the same amount.

Long, lean, and mean. Sleek, high B.C. bullets from 80 to 115 grains help the .243 Win. (left), 6mm Rem., and several other .24-caliber cartridges perform better than the venerable .30-30 Win. in the deer fields. Bullets (l-r) are: 80-gr. Nosler Ballistic Tip, 90-gr. Swift Scirocco, 95-gr. Berger VLD Hunting.

Some might argue that the larger diameter of the .308 bullets makes them “hit harder” than the .243 bullet, but really? The energy figures clearly show otherwise. And as for physical effect, do we really think that extra 0.065-inch diameter of bullet difference is going to change much? A 0.065-inch wider bullet? I doubt it.

Terminal bullet performance has less to do with diameter than with how the bullet reacts mechanically. How much does it expand? How deeply does it penetrate? Does it ball up into a smooth lump or spread into sharp edges? Does it fragment and distribute tissue-tearing particles widely or remain in one piece to cut a narrow but long channel?

Having witnessed the impact of dozens of .243 bullets of many styles and construction on dozens of whitetails, pronghorns, feral hogs, coyotes, bobcats, and even one zebra stallion, I’m convinced the .243 Win. and its close cousins—the 6XC, 6×47 Lapua, 6mm Remington, .243 WSSM, 6mm-.284 Win., and .240 Wby. Mag.—are effective deer-hunting cartridges.

For more from Ron Spomer, check out his website, ronspomeroutdoors.com, and be sure to subscribe to Sporting Classics for his rifles column and features.