The .22 rimfire, like the small game hunting that inspired it, is rapidly becoming a historical artifact. And it’s up to us to stop that.

You remember it like yesterday. A .22 rimfire. Your first real firearm. Oh, the possibilities. The adventures. The anticipation. The power and precision. No more holding three inches right and hoping that BB will curve into your target. From here on out, you’ll aim at the cottontail’s head and bingo—Hasenpfeffer for the whole family. Fried squirrel with gravy. A prime red fox pelt for the fur buyer. A raccoon hunt under the full moon.

You and your buddies meet at the edge of town the Saturday after Christmas, out by the first cornfield, and start walking the snowy rows of stubby stalks, jean pockets bulging with 40 long rifle rounds. Ten are already in the magazine tube on the rifle carried at port arms, ready when that first jack rabbit jumps. And then it’s up and away, long legs churning, snow flying, ears laid over its back. You swing with it, through it, push ahead, keep swinging as the little rifle cracks. Six pounds of jackrabbit roll in a burst of snow.

Does that still happen? Do teenagers still dream of twenty-twos, still hone their shooting and stalking skills to a razor edge in farm fields and woodlots across middle America? I hope so, but I don’t think so. I can count on two fingers the number of times I’ve seen young men walking winter fields with their .22s in the last decade.

More’s the pity.

The .22 rimfire, like the small game hunting that inspired it, is rapidly becoming a historical artifact. And it’s up to us to stop that. The demonization of firearms over the past 50 years makes this a significant challenge. Parents and grandparents have to counter the stigma society slaps on firearms, counter the inertia of peer pressure and combat the distractions of our brave new digital world. Fortunately, .22 rimfires are here to help. And they do it at least 10 ways:

1. No recoil. Even timid, sensitive kids can properly manage a .22.

2. Soft report. There are no painful muzzle blasts nor blowback.

3. Inexpensive rifles. Families on tight budgets can afford a .22 rimfire. The diminutive Chipmunk single-shot bolt action is sized for extra small shooters, weighs just 2.6 pounds and can often be found on sale for $100. Or go for an exhibition-grade walnut-and-blued Cooper 57-M for $3,225.

4. Inexpensive ammunition. I just did a quick internet search and found 50-round boxes of standard velocity Aguila .22 Solid Point ammo selling for $3.09. That’s just over 6 cents per shot.

5. Long small game seasons. Tree squirrel and rabbit seasons in many states are open for months at a time. Many rodent pests and invasive species like starlings can be hunted year-round. To a kid—or any new hunter— pursuing squirrels or bunnies is a grand adventure, bagging one a fulfilling accomplishment.

6. Large bag limits. Ten cottontails per day in some jurisdictions. As many jackrabbits as you want. Endless woodchucks. There’s no need to quit hunting for 11 months because you’ve filled your tag.

7. Reasonable access to hunting fields. Farms and ranches closed to deer hunting open their gates to careful, respectful, rabbit-and-rodent-hunting kids, especially with adult supervision and mentoring.

8. Limitless and inexpensive plinking targets. Tin cans, dirt clods, balloons, saltine crackers, Necco candy wafers—lots of action targets to keep the entertainment factor high. Birchwood Casey markets an extensive line of reactive steel targets like spinners, dueling plates and self-setting poppers that keep the action going.

9. Relatively convenient shooting ranges. Ten yards is far enough for an effective .22 practice range. Most of us live in close proximity to a safe shooting site, outdoors or in.

10. Versatility. Today’s .22 Long Rifle ammo is loaded with a wide variety of bullet types, from 20 to 60 grains and velocities from 420 fps to 1,850 fps. Subsonic rounds reduce noise, recoil and the need for elaborate range setups. Aquila’s .22 Colibri’ cartridges nudge a 20-grain bullet just 420 fps for only 8 foot-pounds of energy and can safely be used on indoor ranges with appropriate bullets traps and ventilation. Or step it up with Aguila’s .22 30-grain Supermaximum Hollow Point at 1,700 fps for hunting, their unique 60-grain Sniper Subsonic solid at 950 fps that still carries 120 f-p energy at 100 yards.

Ammunition manufacturers like Aguila continue to make it possible to shoot a .22 rimfire.

If this reads as if I’m trying to sell something, I am. Shooting. More precisely, the innocence of sport shooting the way it was accepted in the 20th century when .22 rimfires were ubiquitous and small game hunting was a stepping stone into adulthood. Twenty-twos were the training wheels of maturity, responsibility and trust. They still can be—if we minimize trophy fixation and practice deferred gratification.

The downside to sport hunters’ successful restoration of big game species, from whitetails to kudu, has been our preoccupation with size. Kids pick up on this, often encouraged by adults who direct them toward “bigger is better.” This is fine for an occasional adventure but robs them of countless childhood discoveries and adventures.

What adult doesn’t remember the intense longing for the chance to indulge grown-up escapades like lighting the fireworks, steering the boat, firing the gun or just hanging out in deer camp with the grownups? Who doesn’t recall carrying home that first duck, rabbit or pheasant with an equal weight of pride? What kid won’t benefit from a feeling of autonomy and competence when turned loose for a day in the field with a gun and orders to bring home enough for dinner?

All of this and more can be realized behind the butt of a .22 rimfire.

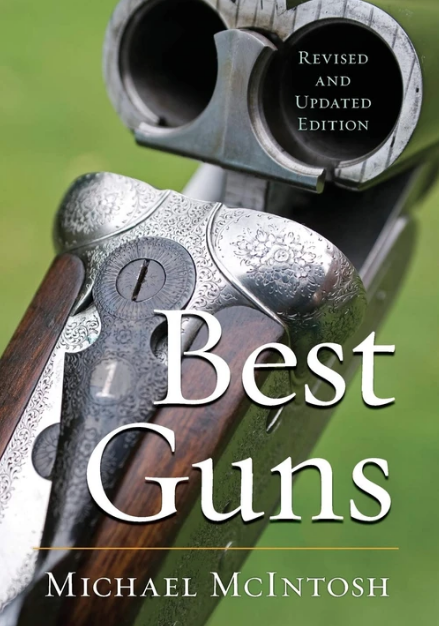

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns – what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns – what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

As interest in fine double guns reaches a new high in this country, Best Guns serves as both a guide for the uninitiated and a standard reference for the experienced collector and shooter, all written with the precision and seamless grace that were Michael McIntosh’s trademark style. Buy Now