A word as to weapons and shooting. When I first came to the plains I had a heavy Sharps rifle, .45-120, shooting an ounce and a quarter of lead, and a .50-caliber, double-barreled English express. Both of these, especially the latter, had a vicious recoil; the former was very clumsy; and above all they were neither of them repeaters; for a repeater or magazine gun is as much superior to a single- or double-barreled breechloader as the latter is to a muzzleloader.

I threw them both aside, and have instead a .40-90 Sharps for very long range work; a .50-115 6-shot Bullard express, which has the velocity, shock, and low trajectory of the English gun; and, better than either, a .45-75 half-magazine Winchester.

The Winchester, which is stocked and sighted to suit myself, is by all odds the best weapon I ever had, and I now use it almost exclusively, having killed every kind of game with it, from a grizzly bear to a bighorn. It is as handy to carry, whether on foot or on horseback, and comes up to the shoulder as readily as a shotgun; it is absolutely sure, and there is no recoil to jar and disturb the aim, while it carries accurately quite as far as a man can aim with any degree of certainty; and the bullet, weighing three quarters of an ounce, is plenty large enough for anything on this continent.

For shooting the very large game (buffalo, elephants, etc.) of India and South Africa, much heavier rifles are undoubtedly necessary; but the Winchester is the best gun for any game to be found in the United States, for it is as deadly, accurate, and handy as any, stands very rough usage, and is unapproachable for the rapidity of its fire and the facility with which it is loaded.

Of course every ranchman carries a revolver, a long .45 Colt or Smith & Wesson, by preference the former. When after game a hunting knife is stuck in the girdle. This should be stout and sharp, but not too long, with a round handle.

I have two double-barreled shotguns: a No. 10 chokebore for ducks and geese, made by Thomas of Chicago; and a No. 16 hammerless, built for me by Kennedy of St. Paul, for grouse and plover.

On regular hunting trips I always carry the Winchester rifle; but in riding round near home, where a man may see a deer and is sure to come across ducks and grouse, it is best to take the little ranch gun, a double-barrel No. 16, with a .40-70 rifle underneath the shotgun barrels . . .

. . . To be remarkably successful in killing game, a man must be a good shot; but a good target shot may be a very poor hunter, and a fairly successful hunter may be only a moderate shot. Shooting well with the rifle is the highest kind of skill, for the rifle is the queen of weapons; and it is a difficult art to learn.

But many other qualities go to make up the first-class hunter. He must be persevering, watchful, hardy, and with good judgment; and a little dash and energy at the proper time often help him immensely.

I myself am not, and never will be, more than an ordinary shot; for my eyes are bad and my hand not over-steady; yet I have killed every kind of game to be found on the plains, partly because I have hunted very perseveringly, and partly because by practice I have learned to shoot about as well at a wild animal as at a target. I have killed rather more game than most of the ranchmen who are my neighbors, though at least half of them are better shots than I am.

Time and again I have seen a man who had, as he deemed, practiced sufficiently at a target, come out “to kill a deer,” hot with enthusiasm; and nine out of ten times he has gone back unsuccessful, even when deer were quite plenty. Usually he has been told by the friend who advised him to take the trip, or by the guide who inveigled him into it, that “the deer were so plenty you saw them all round you,” and, this not proving quite true, he lacks perseverance to keep on; or else he fails to see the deer at the right time; or else if he does see it he misses it, making the discovery that to shoot at a gray object, not over-distinctly seen, at a distance merely guessed at, and with a background of other gray objects, is very different from firing into a target, brightly painted and a fixed number of yards off.

A man must be able to hit a bull’s-eye eight inches across every time to do good work with deer or other game; for the spot around the shoulders that is fatal is not much bigger than this; and a shot a little back of that merely makes a wound which may in the end prove mortal, but which will in all probability allow the animal to escape for the time being.

Roosevelt in full hunting regalia. (Photo: Theodore Roosevelt Center)

It takes a good shot to hit a bull’s-eye offhand several times in succession at a hundred yards, and if the bull’s-eye was painted the same color as the rest of the landscape, and was at an uncertain distance, and, moreover, was alive, and likely to take to its heels at any moment, the difficulty of making a good shot would be greatly enhanced.

The man who can kill his buck right along at a hundred yards has a right to claim that he is a good shot. If he can shoot offhand standing up, that is much the best way, but I myself always drop on one knee, if I have time, unless the animal is very close.

It is curious to hear the nonsense that is talked and to see the nonsense that is written about the distances at which game is killed. Rifles now carry with deadly effect the distance of a mile, and most middle-range hunting rifles would at least kill at half a mile; and in war firing is often begun at these ranges. But in war there is very little accurate aiming, and the fact that there is a variation of 30 or 40 feet in the flight of the ball makes no difference; and, finally, a thousand bullets are fired for every man that is killed—and usually many more than a thousand.

How would that serve for a record on game? The truth is that 300 yards is a very long shot, and that even 200 yards is a long shot. On looking over my game book I find that the average distance at which I have killed game on the plains is less than 150 yards.

A few years ago, when the buffalo would stand still in great herds half a mile from the hunter, the latter, using a long-range Sharp’s rifle, would often, by firing a number of shots into the herd at that distance, knock over two or three buffalo; but I have hardly ever known single animals to be killed 600 yards off, even in antelope hunting, the kind in which most long-range shooting is done; and at half that distance a very good shot, with all the surroundings in his favor, is more apt to miss than to hit.

Of course old hunters—the most inveterate liars on the face of the earth—are all the time telling of their wonderful shots at even longer distances, and they do occasionally, when shooting very often, make them, but their performances, when actually tested, dwindle amazingly.

Others, amateurs, will brag of their rifles. I lately read in a magazine about killing antelope at 800 yards with a Winchester express, a weapon which cannot be depended upon at over 200, and is wholly inaccurate at over 300, yards.

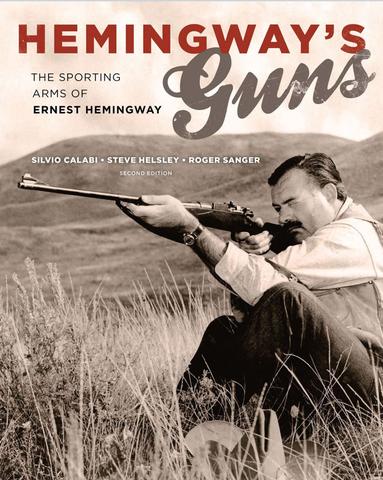

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now